The first time I saw Renate Bertlmann’s Schwangere Braut im Rollstuhl (Pregnant bride in wheelchair), I was transfixed. In this now legendary 1976 performance, she reimagines pregnancy as disability: lurching around dressed in a white dress and veil, her features picked out with rubber bottle teats fixed in a grimace. Finally, the artist-creature heaves out a fake baby, and shuffles off, disinterested and unburdened. Watching the video on my laptop aged nineteen, I had never seen a more confrontational piece of art; such a forceful attack on these supposed pinnacles of female joy—marriage and children—debased with fierce, coarse irony. It made me excited about art as a thing that women could use to aggressively criticise and reject social expectations.

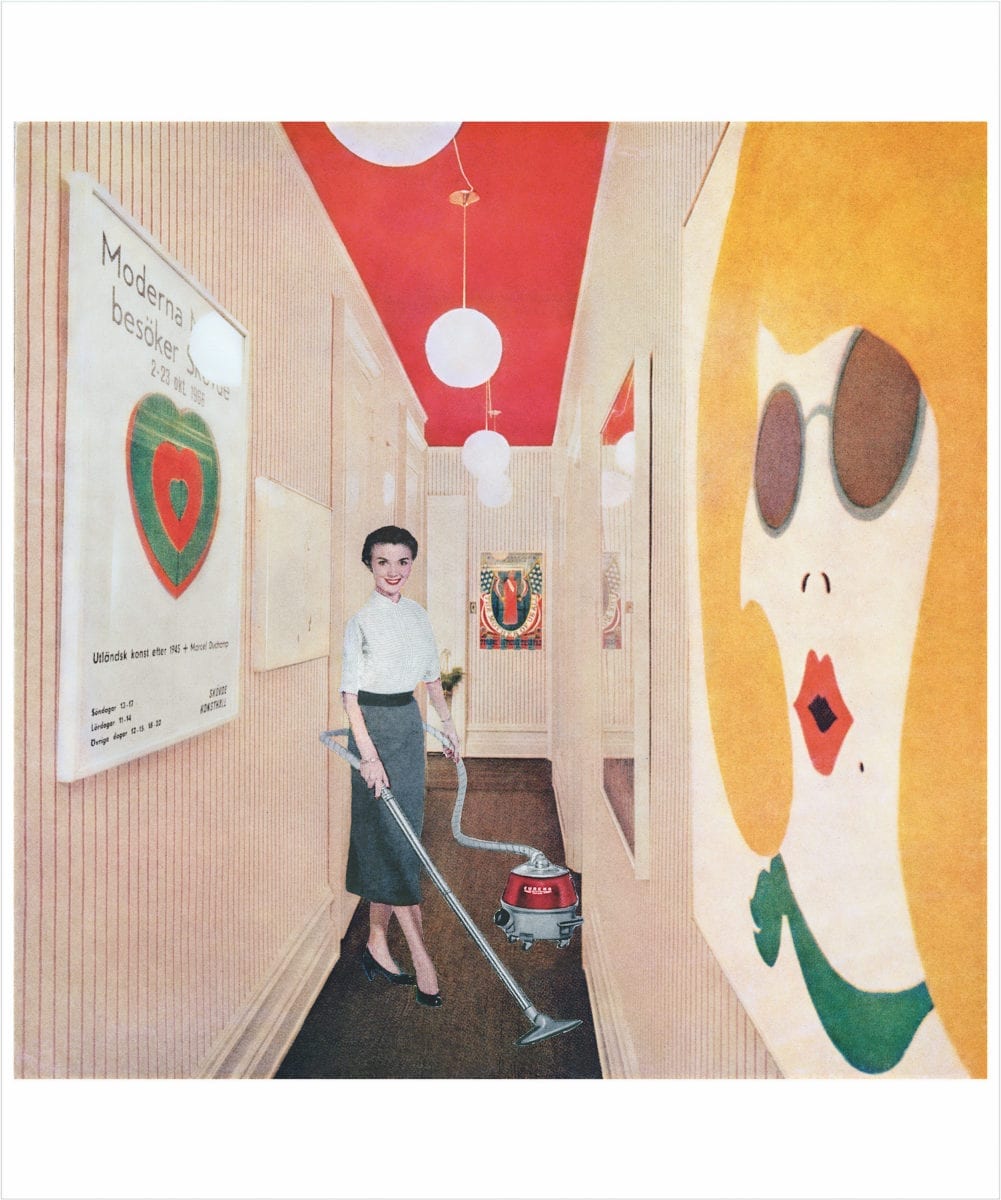

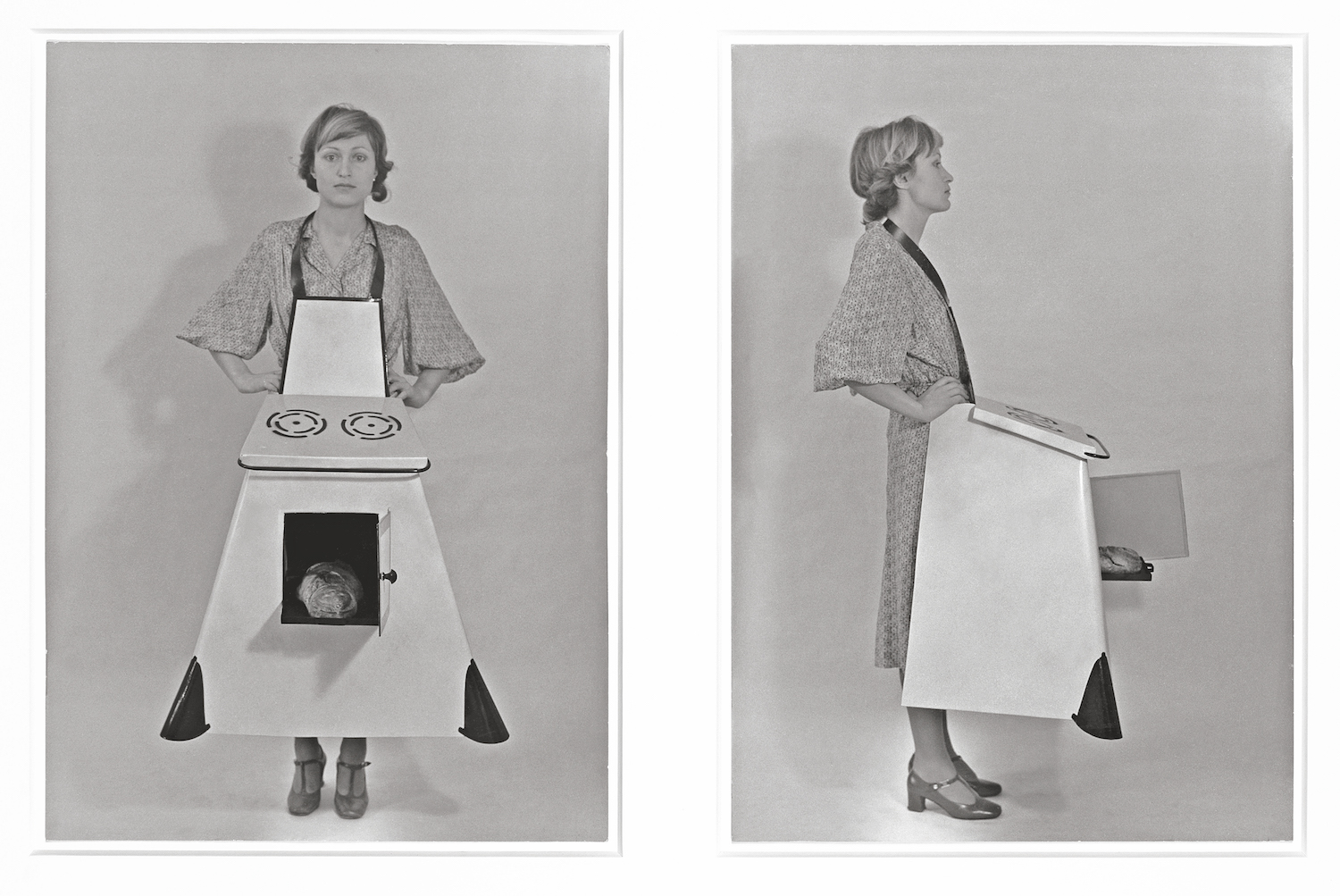

Women House addresses another emblem of female bliss—domesticity and the home. The book is made to accompany the exhibition first shown last year at Monnaie de Paris, and pairs essays with a beautifully expansive series of photographs, organized according to each exhibition section. The show used the seminal feminist art installation and performance space WomanHouse, 1972, as a point of departure. The work, initiated by Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro, articulated frustration at being shut out of the art scene by evading the gallery space altogether. Instead, the pair led a team of women artists who leased and physically renovated an old Hollywood mansion from which they presented a month-long immersive programme of exhibitions and discussions.

Riding the wave of that angry, transformative energy of the 1970s, described definitively by co-author Gabriele Schor as the feminist avant-garde, Women House traces the impact of those legacies, positioning women artists as “thought leaders” about gender and the home. We are asked to consider the home as a dual space—a refuge and prison—though the second thought is more fully explored throughout. The ferocity I felt within that Bertlmann performance is glimpsed in Mona Hatoum’s electrified utensils in Home (1999), which imparts a strange, malevolent autonomy onto ordinary kitchen objects. Lucy Gunning’s work Climbing Around My Room (1993) gives the impression of a pacing tiger—exerting an unnatural charge and feeling of danger in the space.

“We are asked to consider the home as a dual space—a refuge and prison”

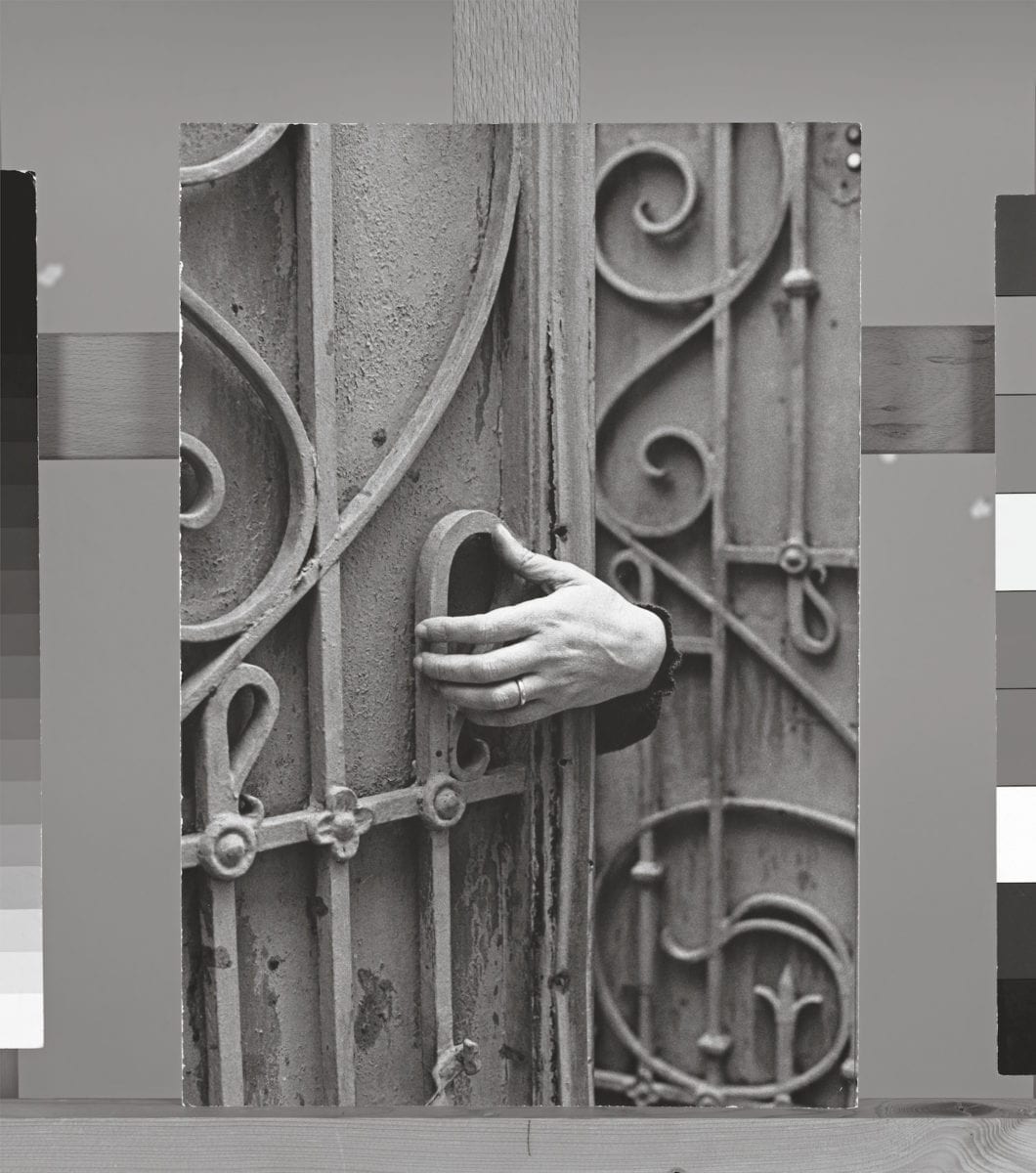

There is a particularly rewarding sequence of what could be called the woman-in-a-cabinet motif, evolved by Claude Cahun, Kirsten Justesen and Francesca Woodman with images that refuse to be easily contained, that play ideas of entrapment and struggle against comfort and security. The section that these works appear in, called A Room of One’s Own, is one of the strongest in the book, and includes Zanele Muholi’s 2007 photograph of a lesbian kiss behind a stove—a scene of quiet and tender intimacy that provides a counter-reminder of the home as a place also of privacy, freedom and safety.

There are moments where the exhibition becomes itself a little fenced in by its own subject matter; you can feel the content straining slightly against its own parameters in Shen Yuan’s Hair Saloon (2000), a creeping fibrous mound that seems sinister, yet protective over a scattering of hen eggs, its fragile cargo. By contrast, Laurie Simmons’s dollhouse mise-en-scènes play it too straight. These, amongst a whole section given over to dollhouses, throw most keenly into relief the bourgeois assumptions that underlies some of these works—the portrayal of lives lived in nicely decorated houses with several storeys expects recognition by the viewer, which is not always there.

Leaving this unchallenged is a problem that risks undermining the book as a whole. For example, Women House does not engage with allegations around the labour process of the original WomanHouse performance from 1972—which ranged from accusations of cliqueyness to abuses of hierarchy. It would be good to see this context used in a reinterpretation of some of the older works in the show: just as many of these pioneering artists sought to tear down the impulse toward hero-worship within the male-dominated art world, paying homage to feminist art pioneers can and should involve critique of method and inclusion. The WomanHouse made a new space for liberated practice, but its doors were closed to some.

“Women House could and should take up the baton to advocate for more inclusivity in future feminist practice”

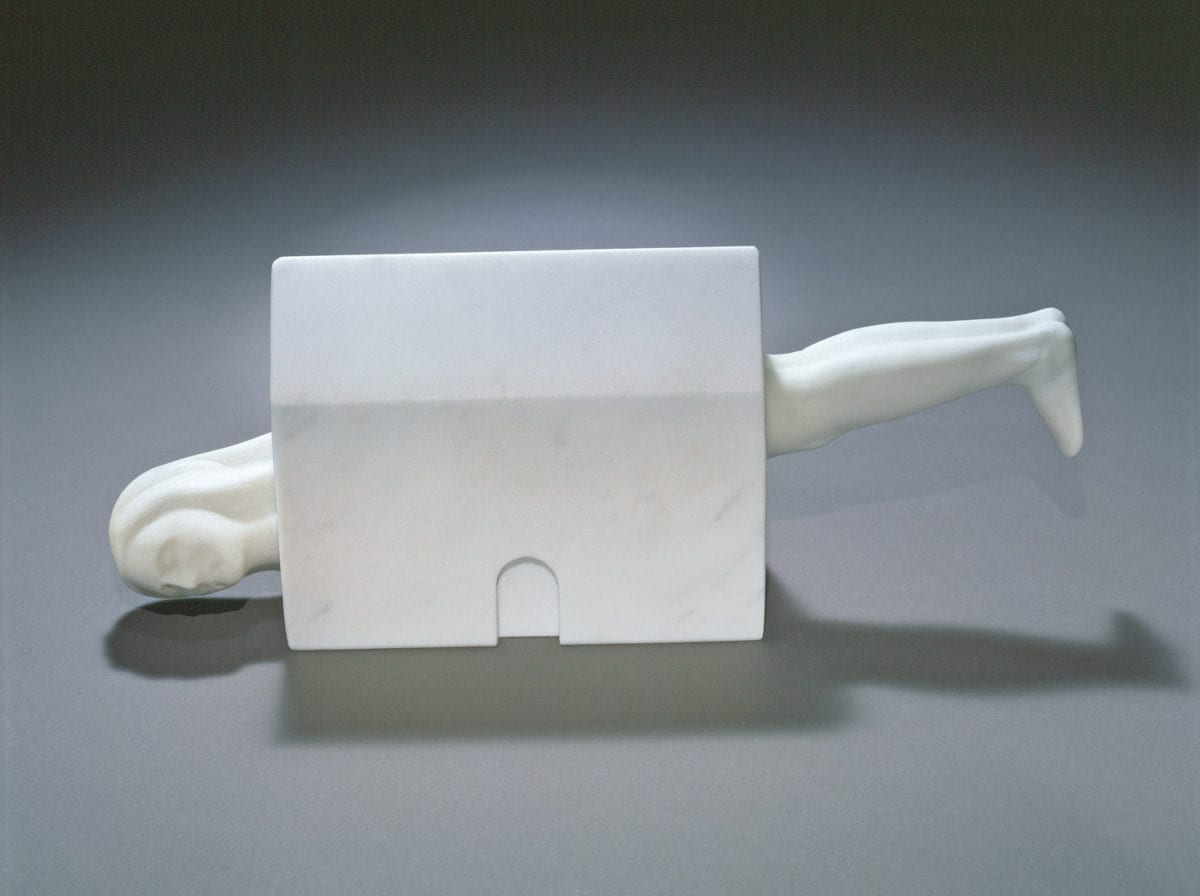

Rachel Whiteread’s House (1993) is introduced as “an iconic monument to British working class life” with no further inquiry. Making a sparse concession that “home” is “always marked by culture, gender and class”, this is a disappointing example of how the writing ducks its opportunity (and some would say responsibility) to engage properly with cultural, social, racial and economic intersectionality. The sculpture, which made her the first female winner of the Turner Prize, was commissioned by Artangel against a backdrop of a social housing redevelopment within spitting distance of Canary Wharf, now one of the most influential centres of economic power in the world.

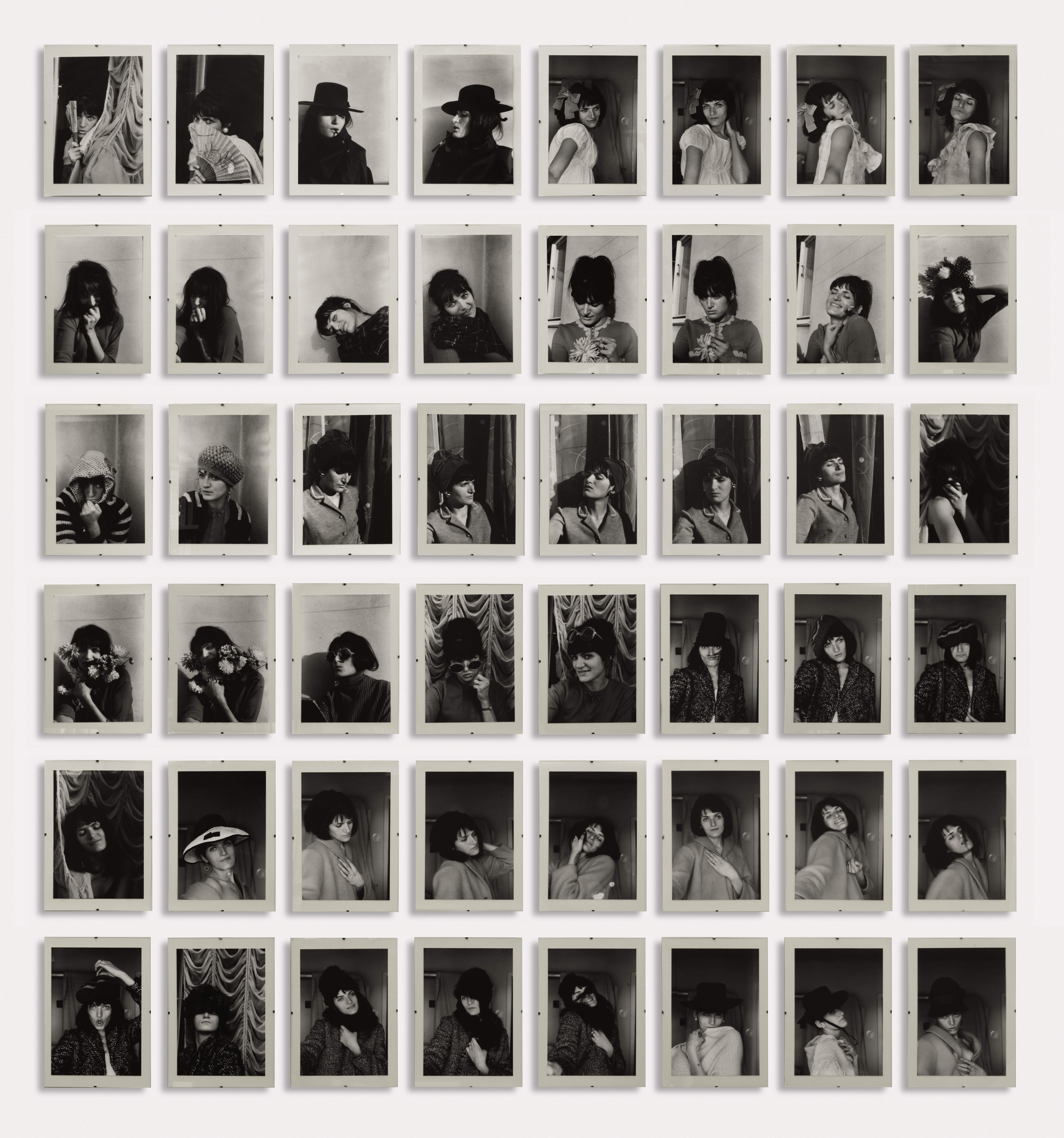

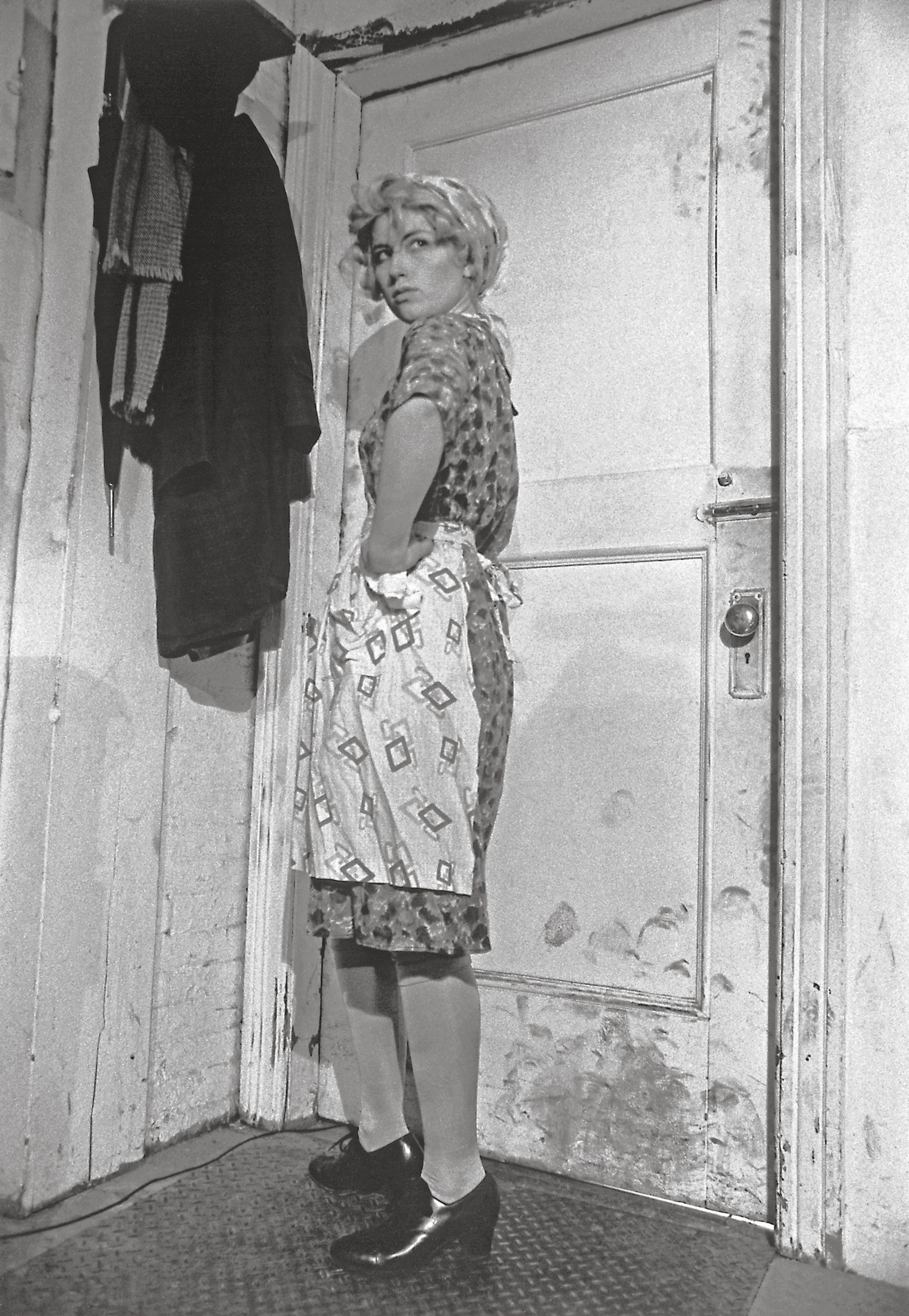

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #35, 1979. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

The gushing reactions within the critical press frequently spilled over into voyeurism that wanted to peer at the materiality of a working class experience without the inconvenience of understanding anybody who was actually living one. Community objections to the work were never treated with equal merit—often dismissed as the philistine protestations of an uneducated group. The absence of such context adds to a sense of imbalance throughout the writing. This kind of critique would strengthen, rather than jeopardize, the case to revisit the influential and celebrated works up for discussion.

The seemingly subtle linguistic change in title from “Woman” in the original 1972 performance to “Women” in this publication indicates a significant shift toward plurality, but this is not fully reflected in the content. While its authors seek to pay due respect to some of the most significant artists of the twentieth century, and comes generously filled with images documenting their works, this book misses an opportunity to replicate the fearlessness of its elders. Women House could and should take up the baton to advocate for more inclusivity in future feminist practice, particularly in the contemporary moment, when curators and critics are compelled to ask challenging questions about who, exactly, is granted representation in the gallery space. It makes it clear that there is still much work to be done.