Two friends, 14-year-old Ekaterina Martynova and 17-year-old Elena Samokhina, were on their way home from a party in 2000 in Ryazan, Russia when they were offered a lift home by Viktor Mokhov and his girlfriend Yelena Badukina. What happened next was a horrific crime that would last almost 4 years. Mokhov drugged the girls and took them to a purpose-built bunker where they were imprisoned and repeatedly raped. Samokhina gave birth three times—two of the babies survived and were taken and abandoned by Mokhov.

Mokhov was sentenced to only 17 years in prison—and was released in March this year. He is now 70. Three weeks after his release, he gave an interview to Russian television with Kseniya Sobchak, (reportedly Vladimir Putin’s goddaughter, and the daughter of the former mayor of St Petersburg) in which, unbelievably, he gives a tour of the bunker and attempts to justify his crimes.

When the artist Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi heard Martynova and Samokhina’s story, and the way the Russian media treated Mokhov, it shook her to her core. “It was extremely hard to see how celebrated he got [sic]. It was hard enough to trigger me to work on this project and bring into my work a subject matter that I have never really dealt with before, which is sexuality”, Cherkassky-Nnadi tells curator Alison M Gingeras in an interview that accompanies her current online exhibition, Women Who Work.

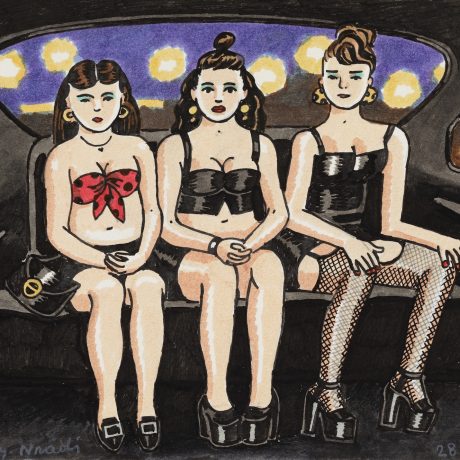

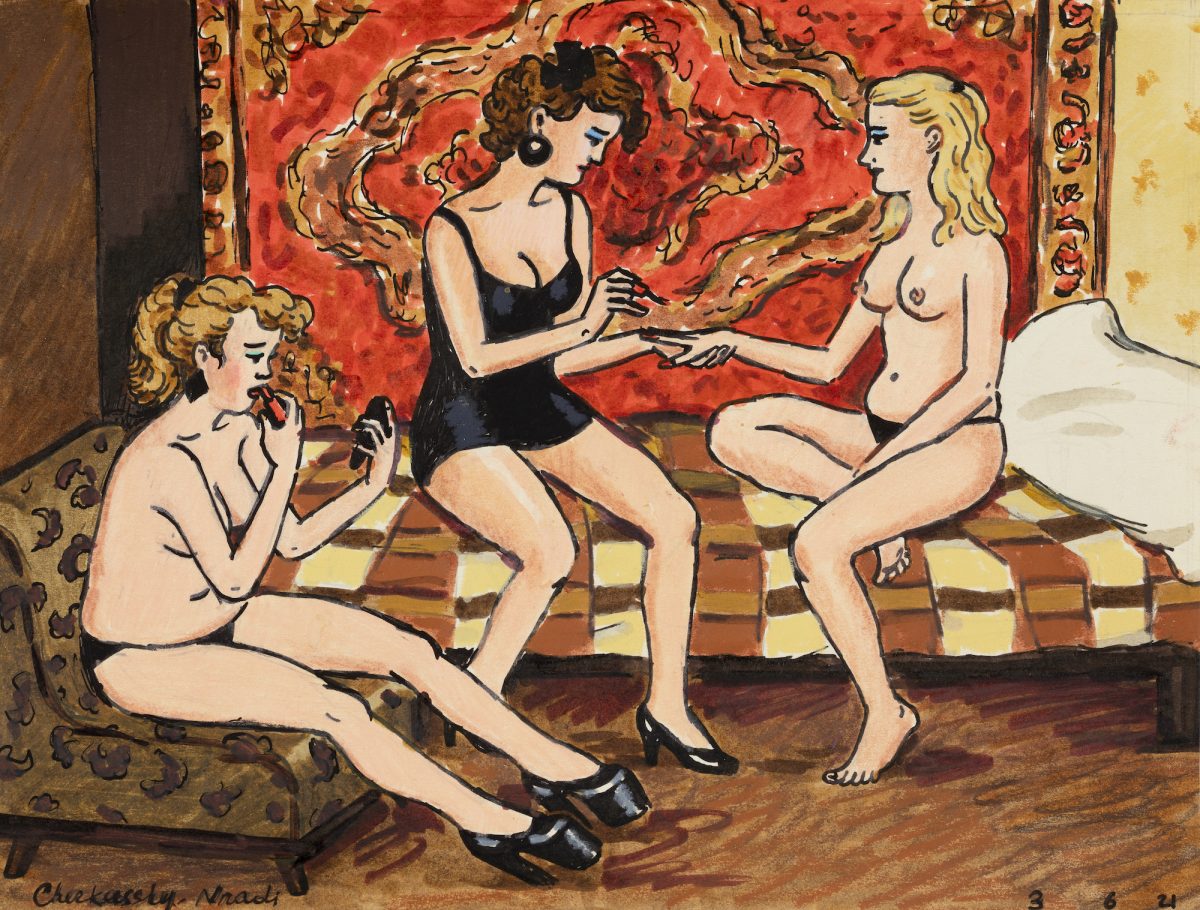

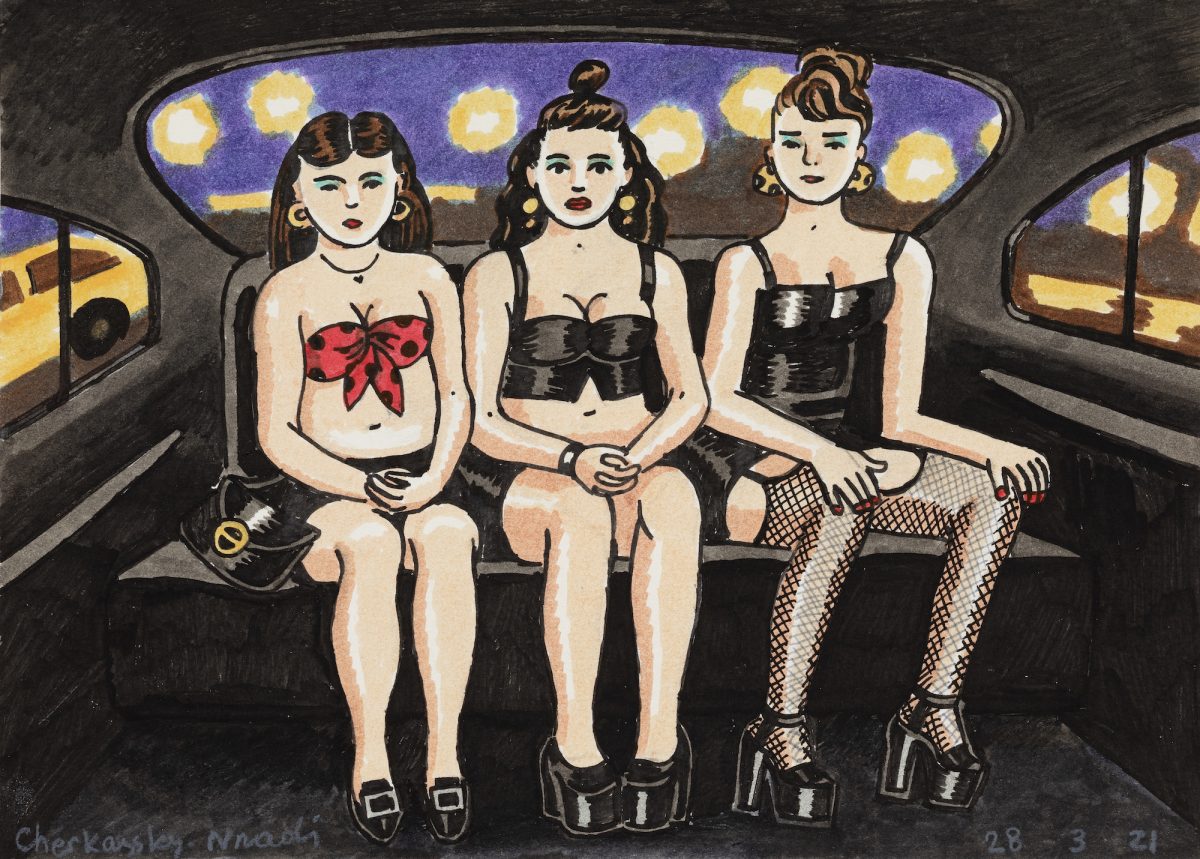

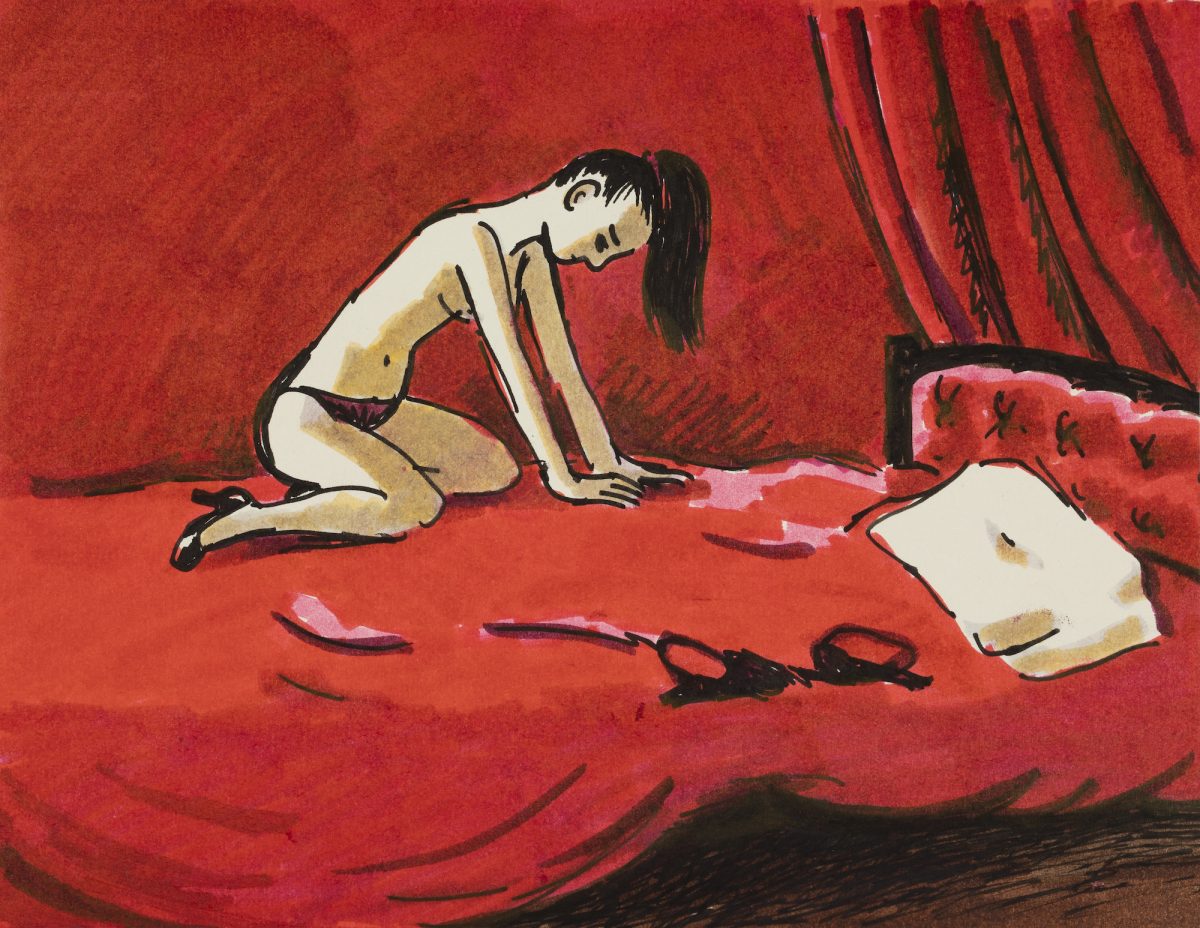

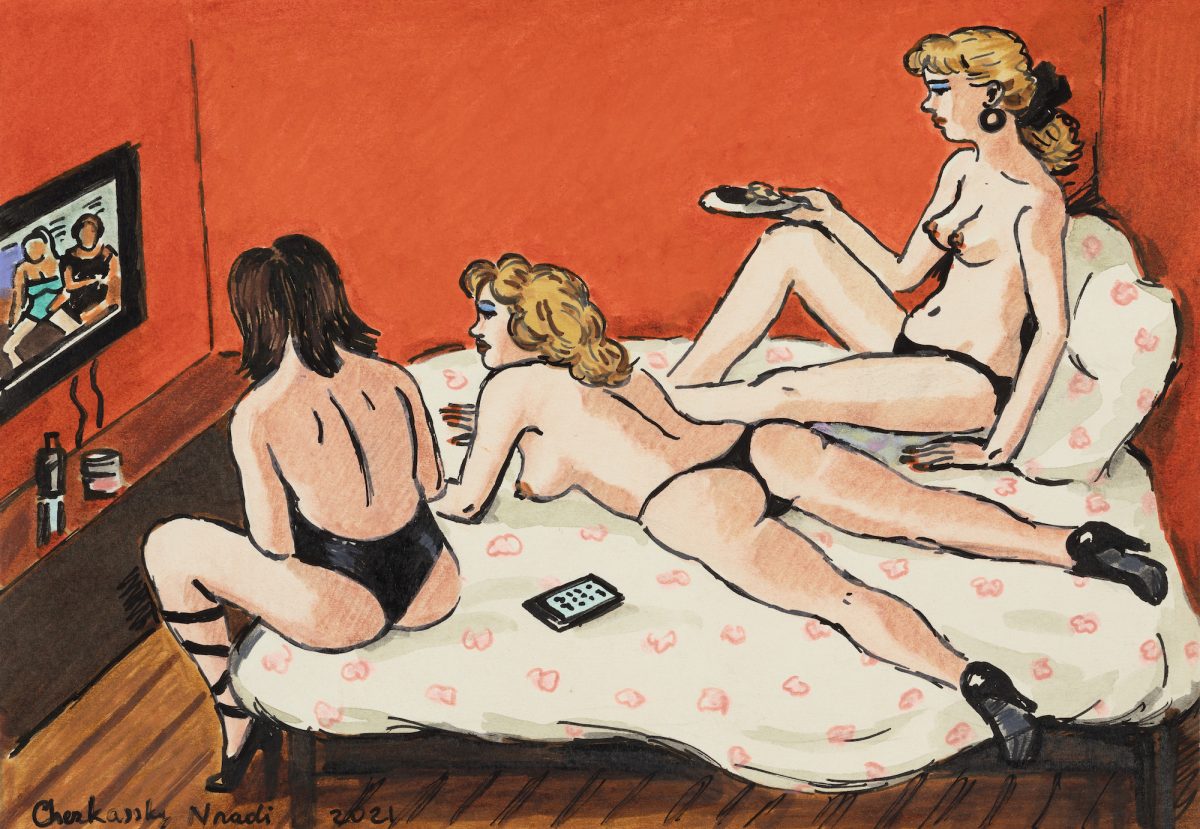

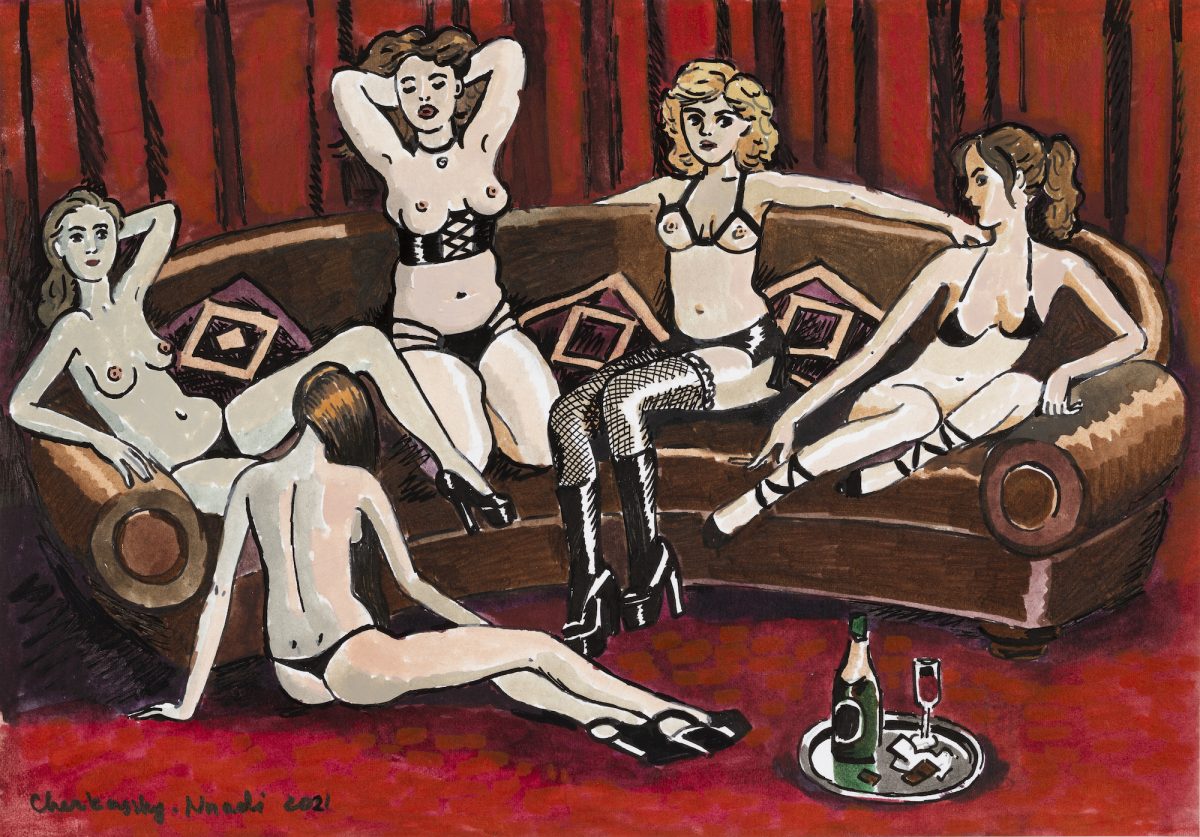

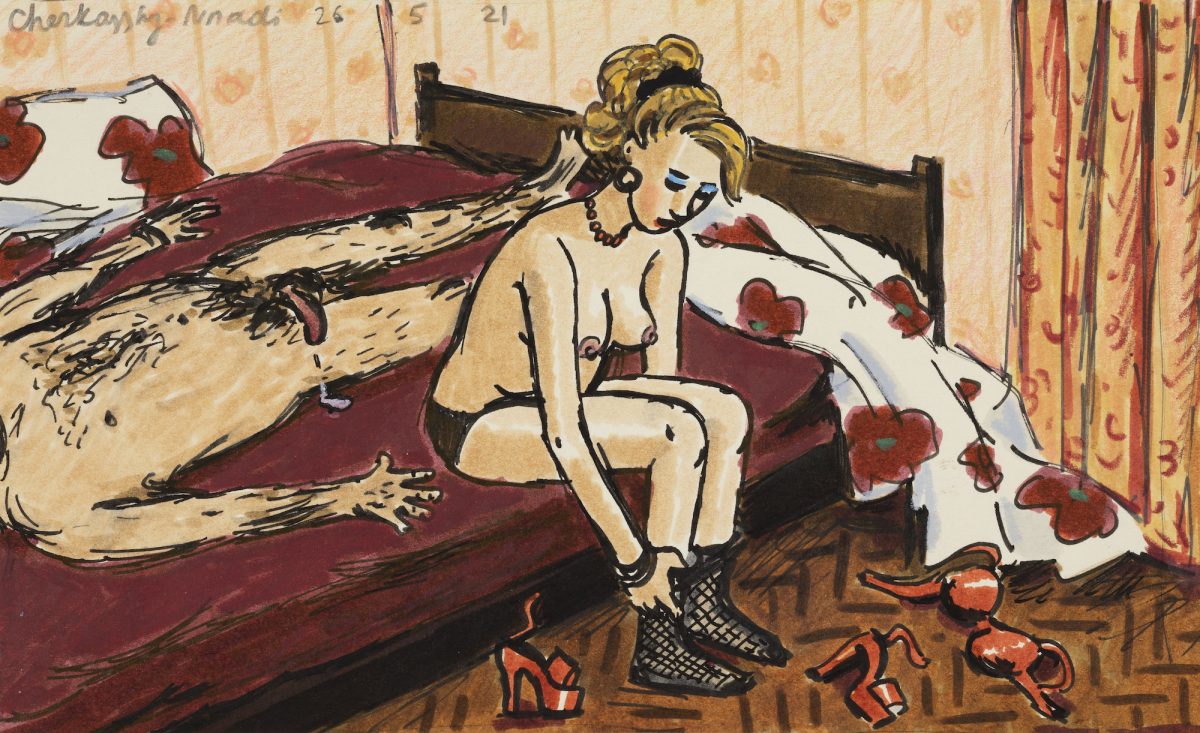

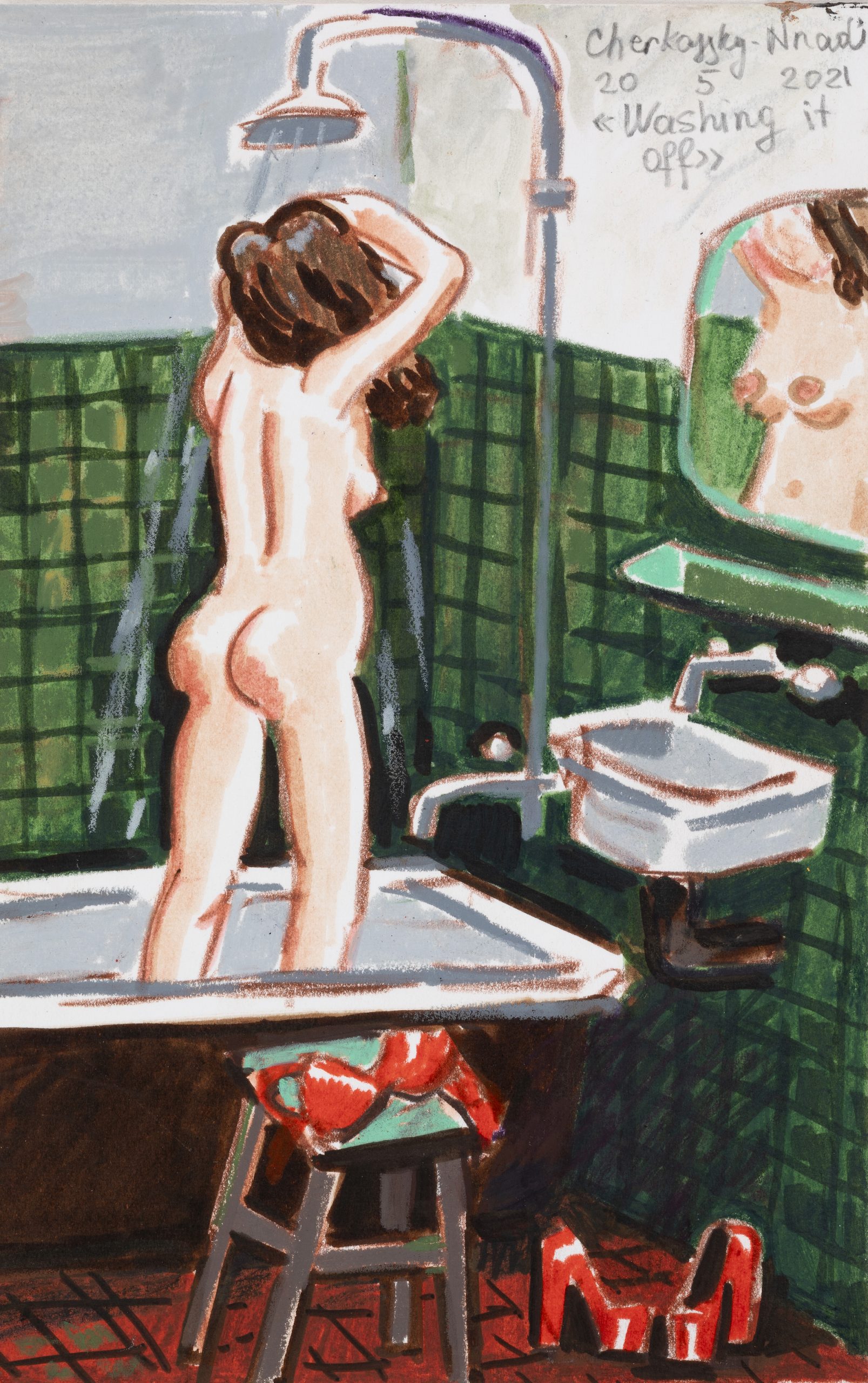

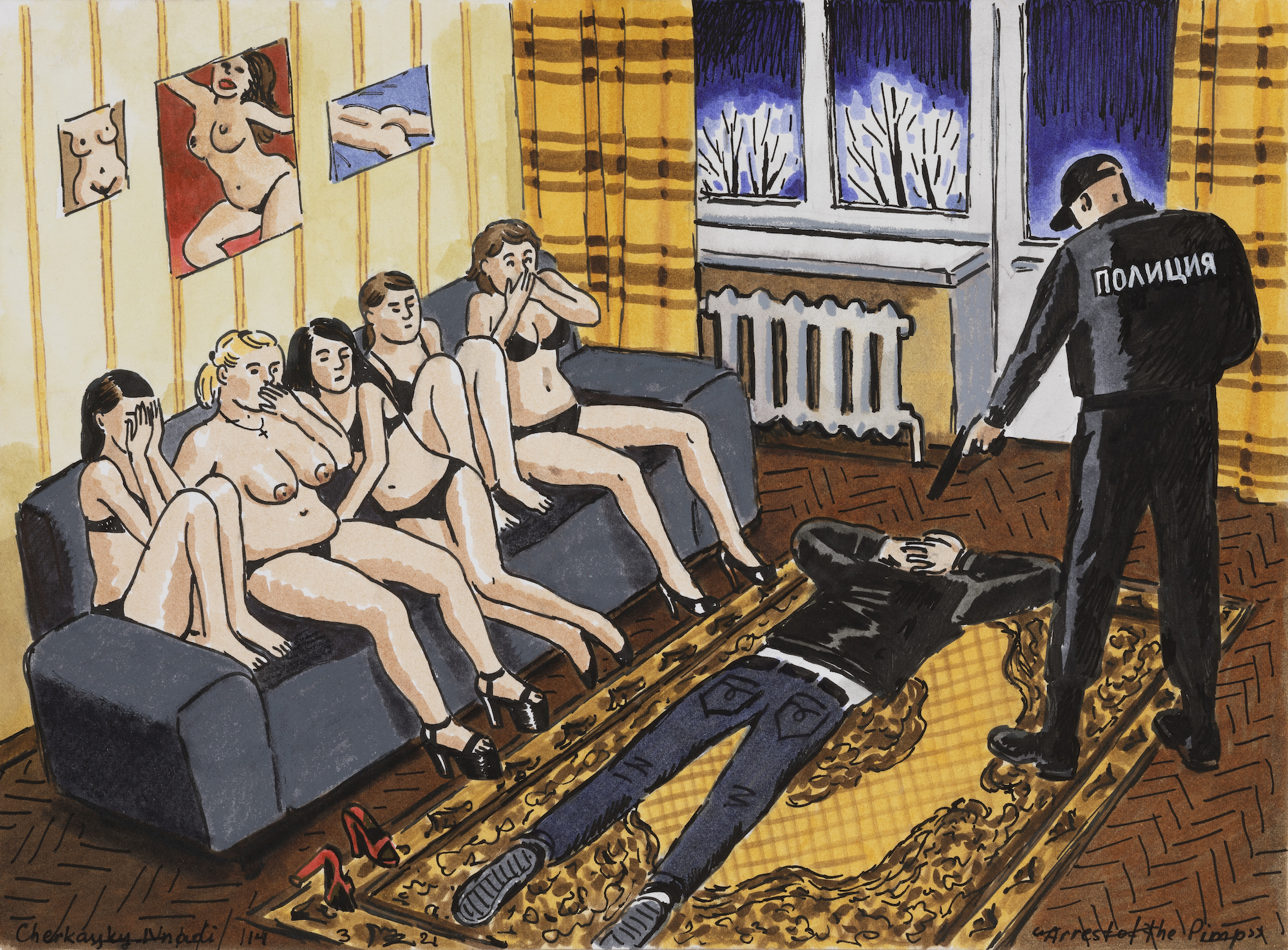

The painter has previously dealt with portraiture, particularly Soviet and post-Soviet life, but her latest body of work abruptly shifts these familiar domestic settings. They are threatened spaces, even in the moments where women are alone, dressed in underwear, still ready to be subjected to male objectification and assumed to be available for exploitation.

“They are threatened spaces, even in the moments where women are alone, still ready to be subjected to male objectification”

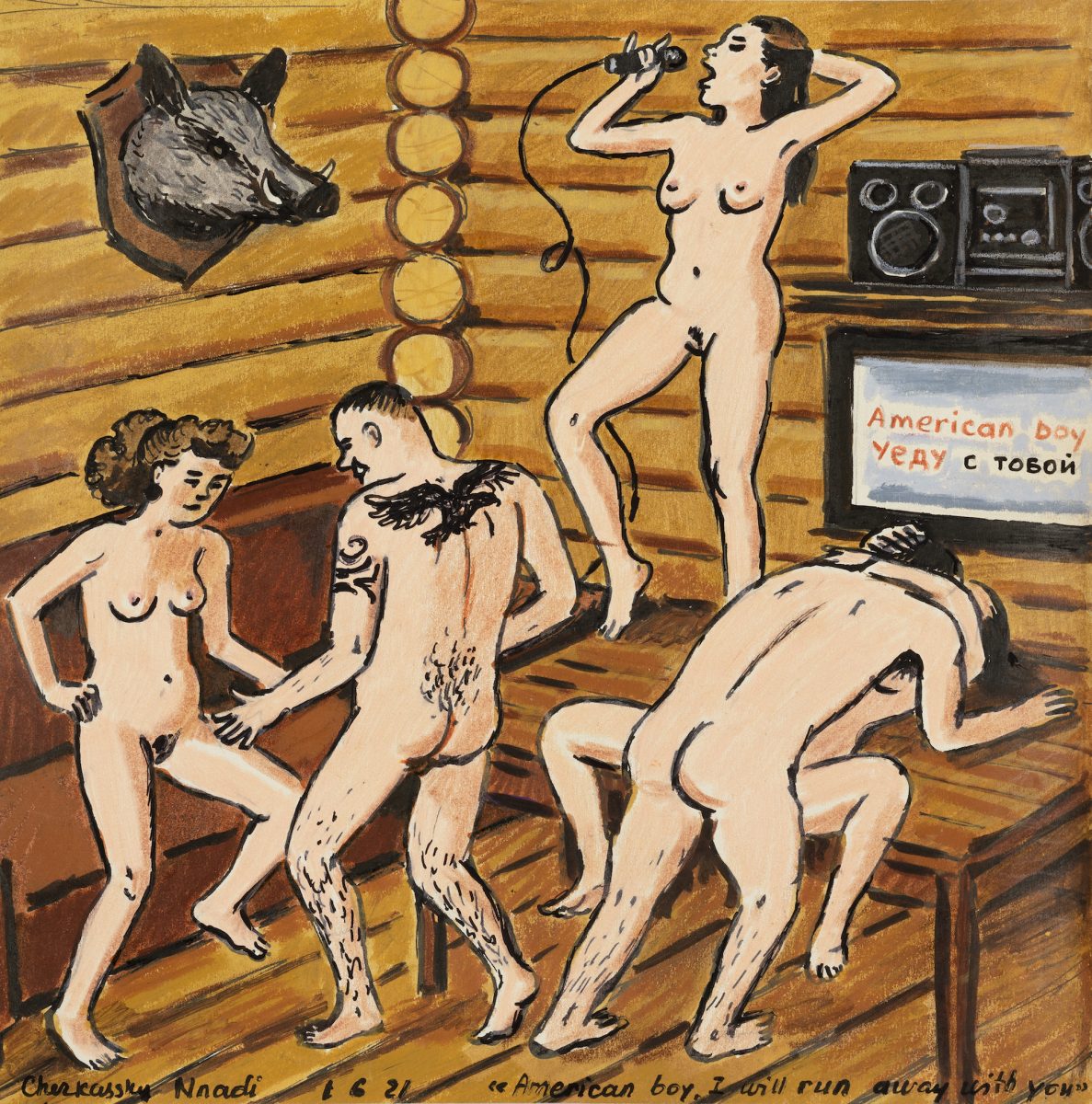

There is not a straight line from what happened to Martynova and Samokhina to the drawings by Cherkassky-Nnadi. Born in Kiev in 1976, she grew up under the Soviet rule and migrated to Israel in 1991 as the Soviet Union collapsed. Produced during a period of lockdown in Israel during the last year, the works were a reaction to that horrific story, and an unflinching exploration of the predatory side of sex.

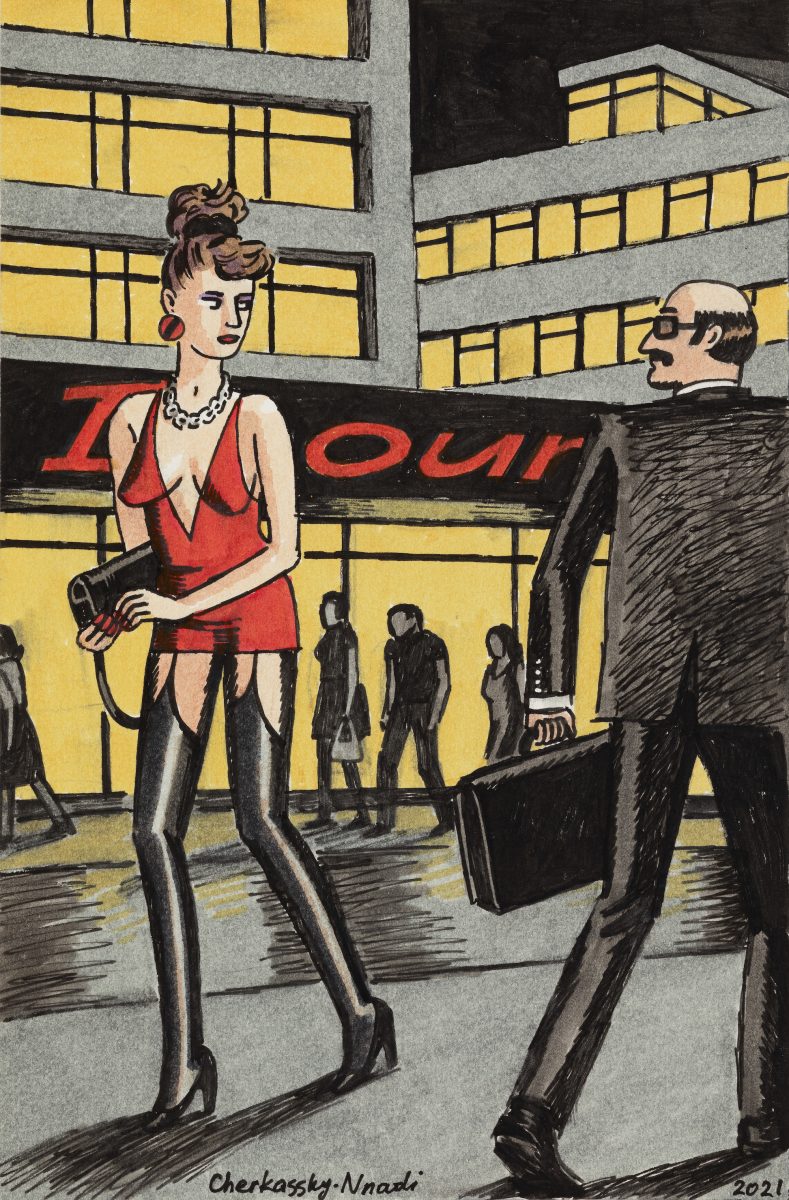

They depict sex workers, none of whom were known to the artist personally, and that distance is reflected in the perspective shown in the paintings. She painted women who were working on the street, who she observed from her studio window in Tel Aviv. Other portraits reference YouTube videos of sex workers in Russia, some filmed by police, and uploaded with the aim of shaming the women.

Several paintings show solitary female figures seen from behind, and Cherkassky-Nnadi explains that she was inspired by the protagonist in the Soviet drama Intergirl (1989), which followed the story of a nurse by day who is forced into prostitution to make ends meet. Intergirl is also the film playing on a TV in another scene, in which a group of women unwind together. These scenes contrast palpably with those in which men do appear, where suddenly the mood becomes tense with sex or violence—or the implication of it.

Cherkassky-Nnadi’s decision to paint from this mix of references adds a further layer to these portraits: it’s not only about the women who work, it is about the way the artist sees them. It is about the way others see them and choose to depict them, too, whether it’s in pop culture or on the streets. Ultimately it isn’t these working women that are challenged, it is our own cloudy perceptions. The women, and their agency, remain at a distance.

Charlotte Jansen is a freelance arts writer. Her latest book, Photography Now, is out now

All images courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort