In its preview week, the forty-eighth edition of the Rencontres d’Arles drew 17,500 international visitors. The sprawling festival includes forty exhibitions in twenty-five venues across the city, with more than 250 photographers invited by thirty exhibition curators. The festival is split up into numerous sections including Latina!, The Experience of Territory and World Disorders. At the inauguration, Françoise Nyssen, the French Minister of Culture, paid tribute to photography by evoking “the necessity of an art that fixes the gaze, stops time for us, at a time when we no longer take it.”

Arles, the city in southern France, has been well known within the world of photography in recent decades. With its Roman and medieval heritage, a listed Unesco site, the city lends its churches and cloisters for the festival every year, providing an extraordinary and often poetic setting. In addition, this year the huge Luma Foundation for Contemporary Creation has provided four recently renovated industrial buildings dating from 1856.

The Swiss curator Maja Hoffmann presents Annie Leibovitz Archive Project # 1: The Early Years. This reproduction of the American photographer’s New York studio includes a selection of hundreds of photographs from an archive of nearly three thousand photographs that the Luma Foundation bought from the beginning of the artist’s career. Images shot between 1970 and 1983 are pinned to the wall, many from Rolling Stone magazine, showing intimate moments of Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono and John Lennon, as well as Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and US presidents such Carter and Nixon.

This edition of the festival establishes a picture of global politics, including two international artistic scenes. France and Columbia are currently celebrating their diplomatic relations by hosting “cultural seasons” in both countries. This began in December 2016 in Columbia. For Arles, La Vuelta [The Revolution] at Chapelle Saint-Martin-du-Méjan includes a rare selection of twenty-eight Columbian artists, chosen by the curator Carolina Ponce de Leon.

The Columbian Australian artist Maria Fernanda Cardoso also inspects insect penises with the amusingly named MOCO (Museum of Copulatory Organs), enlarging them from microscopic images to large format. Edwin Sánchez explores the Colombian urban experience, presenting two photographs of a Wesson 38 gun bought on the black market in Bogotá, on which remarks from artists or delinquents are engraved. The work, Insertion into Ideological Circuit, (2010) questions the limits of the legality and ethics of art. The gun was sold back onto the black market. Andres Felipe Grjuela’s work around archive images is even more violent, especially the page of a sensationalist newspaper titled “Fugitive man on the run caught by the police”—actually, he was beaten by the police.

The Colombian conflict of the last sixty years with the FARC—which was recently ratified—occupies an entire floor at the festival. Here we find Clemencia Echeverri’s video of the Cauca River, a real mass grave. Part of a bigger project, Requiem M / W by Juan Manuel Echavarría describes decorated tombs of unidentified victims adopted by the population of a village, sometimes giving their own names to the dead. Of course, there is a room devoted to Oscar Muñoz, with a series of fragile portraits, immersed in water, about memory disappearance.

The other national focus is at the city’s Église Sainte-Anne. Iran, Year 38 combines sixty-six Iranian photographers, including many young people and women, working from the Islamic revolution in 1979 to the present day. These images come from all over the country and have been selected by two female Iranian curators, Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh (Silk Road Gallery) and Newsha Tavakolian (Magnum). Displayed similarly to collective works, these photos create a real story of Iranian life and politics—especially poignant are Grape Garden Alley, the black and white series depicting marginalized women living in a social housing by Tahmineh Monzavi, and Kaveh Kazemi’s 1988 May 11, which depicts Bastji women learning to use gas masks during the Iran-Iraq War. Other key works include The Remembrance by the famous Iranian photographer Jassen Ghazbanpour, in which a magnificent desert panorama is dotted with black spots, and the great photo montages of Shadi Ghadirian. We also see how, thirty years on, the war still haunts the imagination of the young, with an especially poignant photograph of newlyweds in a car’s carcass, pictured by Gohar Dashti in the series Today’s Life and War (2008). Mehregan Kazemi emphasizes the alienating relationships in her own family with a montage of photographs of her childhood all linked with a wire.

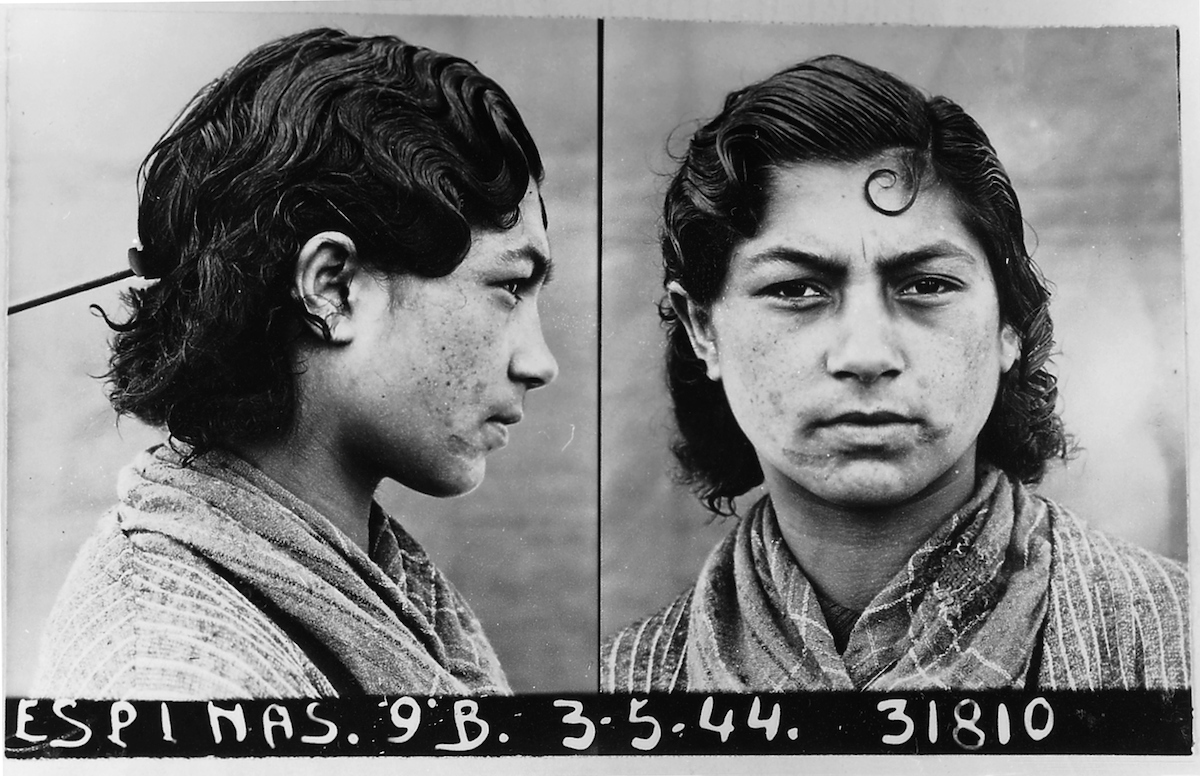

The festival addresses many other social issues with monographic exhibitions. French artist Samuel Gratacap conveys a narrative about the condition of migrants in Libya, with victims’ audio testimonies. A beautiful series about a Gypsy family, The Gorgans, from French photographer Mathieu Pernot, retraces its story from 1995, when he first met the family as a photography student in Arles, until 2017, through deaths, prison sentences, weddings and births, where life develops like wildflowers with mad strength. Swiss photographer Niels Ackermann and the French journalist Sebastien Gobert broach another political subject with a series of images depicting destroyed statues of Lenin, an overview of the post-communist Ukrainian landscape that is haunted with its 5,500 statues of the Russian Marxist leader.

In Guy Martin’s The Parallel State, the British artist immerses himself in Turkey’s political landscape, from the 2013 Gezi Park protest, in which twenty-two people died, through to 2016’s failed coup and purges, mixed with images taken behind the scenes on a Turkish soap opera. The dictatorial policy of Erdoğan takes on the air of a television series à la Big Brother. Martin is exhibited in line with the 2017 Discovery Award with Brodbeck & de Barbuat. Their installation In Search of Eternity II, Japan (2013-2015) reveals Japanese society through a video inspired by Wim Wenders’s Wings of Desire and a Sioux tale of North America where the spirit of the dead floats between heaven and earth, and a series of diaphanous and hazy photographs of Japanese city-dwellers are printed on Japanese paper and exposed, above the video, in a semi-circle.

Elsewhere, Dans l’atelier de la Mission photographique de la Datar, an exhibition of fifteen photographers includes Robert Doisneau (surprisingly, in colour), Josef Koudelka, Christian Milovanoff and Sophie Ristelhueber engaging with the Datar, a French state urban planning institution. The images convey the launch and the experience, between 1983 and 1989, and contain abstract experiments from the suburbs of Paris. American artist Michael Wolf also has a solo monographic exhibition Life in the City, which stands alone in a church. It contains expansive photographs of housing developments in Tokyo, Hong Kong and Chicago.

The most unexpected exhibitions in Arles are, however, The House of the Ballenesque

(2017) by American artist Roger Ballen—an in situ photographic installation that plunges the viewer into the darkness of a theatrical haunted house—and the first European retrospective of the Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase, which focuses on his intimate family life until 1992 (the year of his coma, he died in 2012), with self-portraits and unique large format Polaroids with graphic colour interventions. The installations of the Spanish collective Blank Paper (founded in 2000 in Madrid) are a revelation, especially with the very beautiful black and white installation, Y Vio Dios Que Era Bueno by Spanish artist Fosi Vegue, perhaps the most subtle political work of all, in which various images of different parts of the body or antique statues’ fragments are placed on the ground, indicating conceptual chaos.

‘The Rencontres D’Arles’ runs until 24 September. rencontres-arles.com