He Xiangyu’s first attempt to swim from the Chinese side of the Yalu River to the North Korean side was unsuccessful, he tells me. “It was at a very broad point in the river. But we couldn’t pick the shortest way over because it was the most heavily guarded.” In his second attempt he reached North Korean soil. Both were filmed as part of The Swim, his new show at White Cube, Bermondsey. As we speak, a clip projected on a loop shows him with partners wearing yellow swim caps: an important and symbolic colour in Chinese culture. What could have happened to him for swimming across? “North Korean soldiers can just shoot you,” he says.

The Chinese artist’s assistant, Siran Chen interprets for him. He Xiangyu mainly answers through Siran. Questions pass from me to her to him and back along that chain, punctuated with little links of recognition or laughter as either He Xiangyu or I guess a meaning before it is made clear. He enjoys this process of translation. “It has a very particular texture. It’s temporary and abstract, while also existing in this moment.”

What gave him the idea for The Swim? “I married my wife in 2012,” he says, “and we moved from Beijing to Pittsburgh. When I revisited my hometown (Kuandian) for the first time in two years, I asked my parents what was going on, what the people were doing, and I got a very strange, distant feeling like I didn’t know it anymore. I had been creating a series of drawings called the Palate Project in America and I was interested in the feeling of being in a foreign place and also more general feelings of the body. After I got that strange feeling at home I wanted to explore what was going on here in a very personal, physical way, in touch with the elements of the town: the water. That river is very familiar to me from childhood. Though as a child I wasn’t quite aware of the North Koreans, my parents are doctors and know the local people, as well as some of the defectors. Most of them weren’t happy to talk about their experience because they are trying to remain hidden. But my parents helped me get in touch.”

The thirty-one-year-old’s work can certainly seem very politically engaged. But there is always something going on to the side. Even with such serious and delicate subject matter, He Xiangyu’s work can feel playfully esoteric: somehow apolitical from within the political eye of the storm. Between 2009 and 2011 he reduced 127 tonnes of cola to a range of viscous substances—ink with which to paint and a fossilized-looking solid resin. The Cola Project was seen to engage with ideas of mass production, waste and the East’s thrall to Western consumerism. But he is much more interested in “not the consuming but the very physical perception of drinking Coca-Cola. I wanted to transform this fizzy feeling into a solid form.” For the Tank Project (2011–13) he trained a factory of women to stitch a to-size T-34 tank, often deployed along the North Korean border, out of fine Italian leather. He had to sneak into an army base to get the measurements. But what interests him most isn’t the statement inherent in the project, or his espionage as an act of art, but how his employees would have had different sensory experiences of sewing the leather: this “collage of collective creativities”.

I assumed going in that he would be very radical. But as we speak, the three of us, I get an impression that his engagement is at a distance. He sees things, even political situations, for their value in creating an artistic environment. Or a “texture”, as He Xiangyu keeps saying. This is evident in The Swim, in which he interviews the Chinese and North Korean inhabitants of his town in Liaoning Province, listening to differing views without imposing anything extraneous or personal.

Trafficked women, with faces blurred to protect their identity, describe their ordeals. One was led over the border with a rope around her waist. One says how well her Chinese husband treats her, another about how she is not allowed to speak of how badly her husband treats her. “He rarely beats me now, but he still scolds and bullies me.” In Korea she worked at a nuclear testing plant. Her husband forbids her from talking about this too. Also interviewed is a Chinese family who bought a trafficked bride for their “shy” son. They feel wronged by the woman, who divorced him and disappeared after they bought her Chinese papers. But the clip screened on repeat as we speak refers to the other arm of the project.

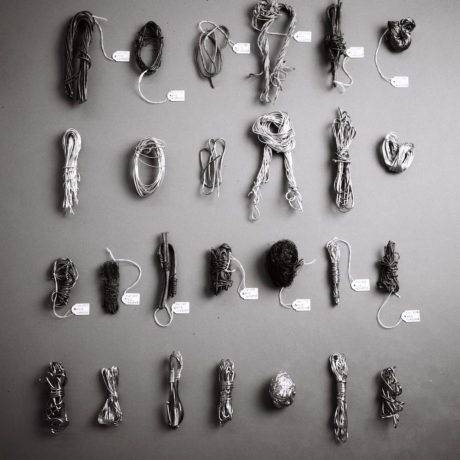

“These people driving this boat are traders,” says Xiangyu. “North Koreans will steal objects from buildings, factories and machines, put them in a bag and leave it on a boat. During the night they’ll take it across the border to the China side and leave it with the goods. The Chinese will come to pick up it up, leave some food or cash in the boat, which will be picked up the following night. I found one of these traders and bought the objects from him.” These scrap metal objects are placed along the White Cube gallery walls; along the floor below there are recreated versions in copper. I say how much I like the work. The three of us laugh.

We walk through the exhibition. I want to talk to him about the idea of labour as part of his process. He hires people, trains them and pays them. How important is this aspect of the work: the support of people but also the time and energy spent going into the work? “At the beginning of Cola Project I boiled the cola without any help from labourers or workers, and it took half a year to finish the one tonne. Then I felt that because cola is mass-produced, if I wanted to make my work compatible to this, I needed some help. If I kept boiling the cola alone, maybe I needed ten years to finish all these 100 tonnes. I asked for the support of workers, and we didn’t work in a hierarchical structure; I worked with them in a quite open environment.”

Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick)

I ask him about what I take to be his most politically engaged work, 2011’s eerily lifelike fibreglass and human hair sculpture of Ai Weiwei lying prone on a gallery floor: The Death of Marat. It addressed how the “dissident” artist was punished for holding anti-establishment views. While doing his Cola Project, He Xiangyu also had to pay fines due to the pollution his work was causing. Did he ever believe the subtext behind these fines was to do with making art? “I hadn’t told anyone I was an artist or this was an artistic project. I just said boiling cola was my hobby. While I was cooking the cola, the whole village smelt sugary. Everyday someone came to ask me why I was cooking cola. ‘This resin that you get from the cola, can you sell it for a good price?’ they’d say. Or they’d ask if they cooked cola at home they could sell the resin to me. Or other people would come and ask if they could drink some. I understand all this, as well as the fines, as part of my art.” Again, I get the impression that the political is less important for him than the space it creates for art to happen. A texture that permeates all his work.

All images courtesy White Cube © He Xiangyu Studio unless otherwise stated