“Something that is kept inside, something in the feeling that never sprouts.” This Chinese proverb, with its allusive wisdom, perfectly encapsulates the allure of New York-based artist Xingzi Gu’s paintings. Gu’s work weaves a rich tapestry of collective knowledge, offering poetic insights into girlhood, melancholia, and eroticism. Their world is a ghostly, hazy, and emotionally charged dreamscape, almost as if seen through tear-filled eyes.

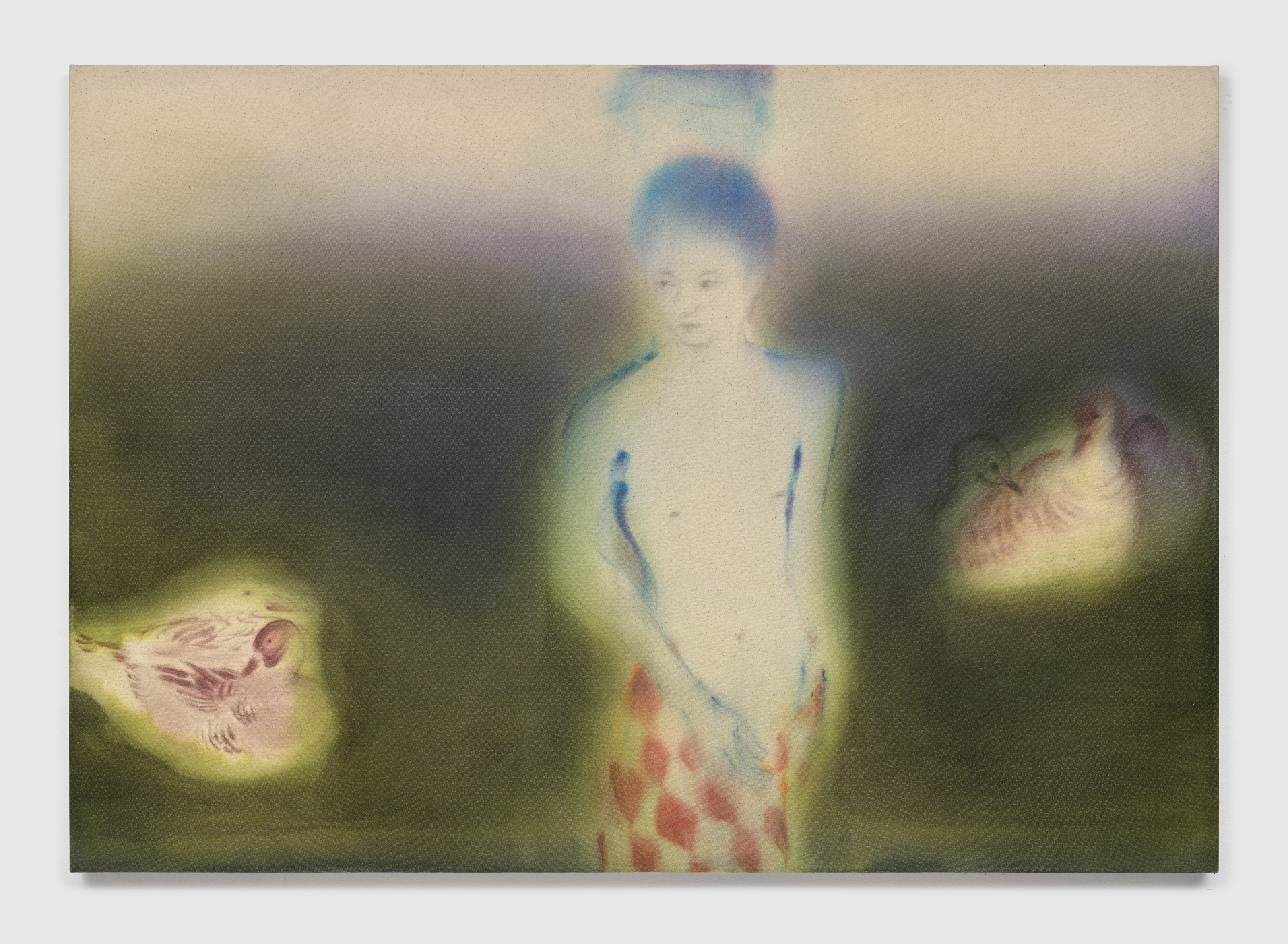

Effervescent environments and unfinished figures capture the complexities of the human experience—the tangible and the intangible bubble together. Gu’s work delves into a delicate and deep abyss, where duality plays a crucial role. The wistful paintings explore the balance between passion and dissociation, loyalty and betrayal, conformity and rebellion, offering a nuanced tribute to our multifaceted lives.

“Painting is a way of reimagining the world or a way of thinking or existing,” Gu explains. “I feel there’s no belief system which I can truly subscribe to, like religion or bureaucracy. Painting is a way to understand what I believe in, explore ideas about belonging and identity with sincerity.”

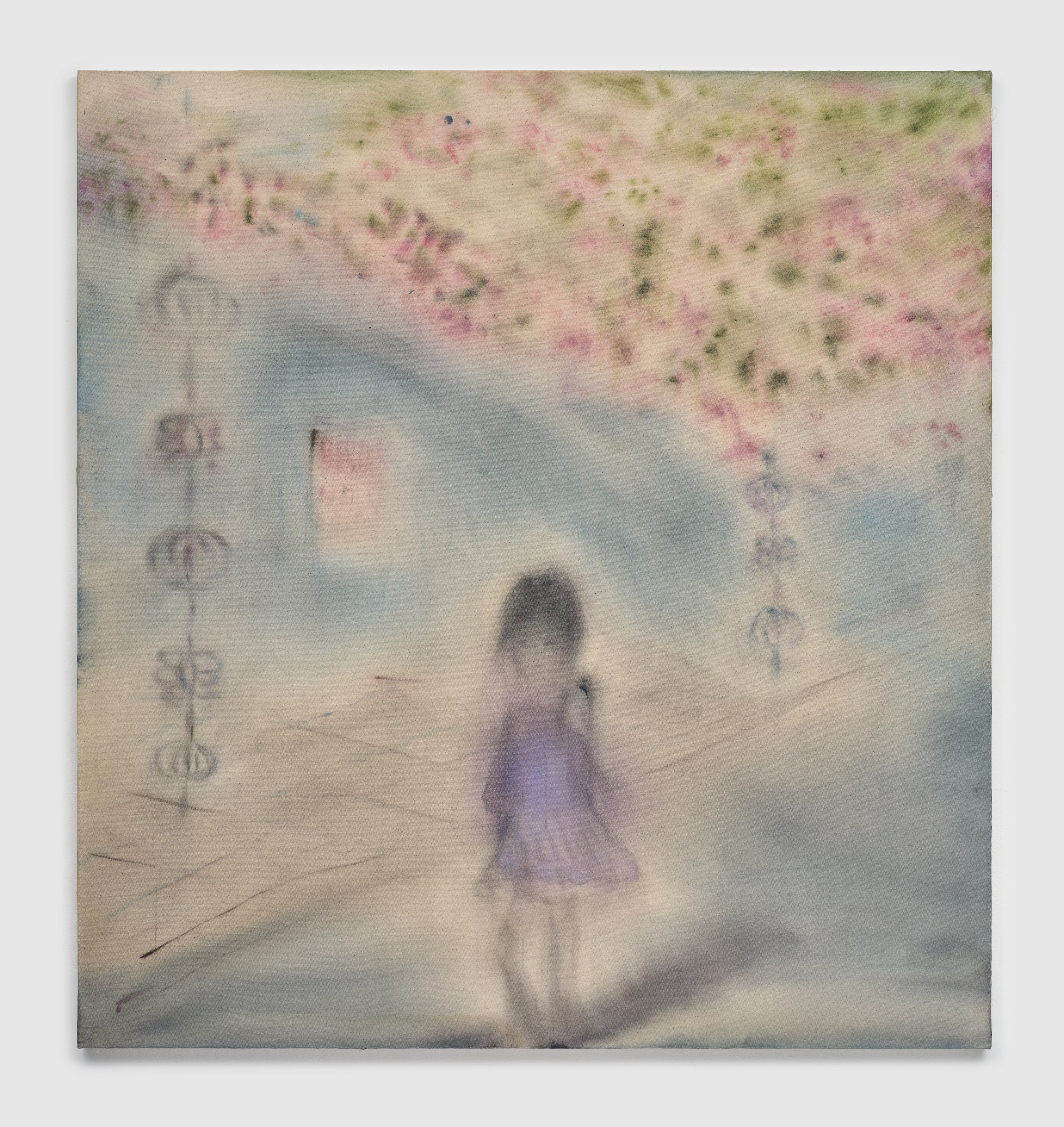

The eight paintings in Pure Heart Hall, on display at Lubov in Lower Manhattan, capture the mystique that permeates our lives. Drenched in soft auras, the works summon a yearning for the unattainable beauty of distant memories. With a dreamlike quality, the diffused light and pastel colors create a distorted, almost otherworldly atmosphere—a love letter to what lies beyond confines.

“I usually look at a lot of images—film stills, random photos online, almost like a teenager scrolling through Tumblr,” Gu shares. I can’t help but compare Gu’s visual and conceptual world to Sofia Coppola’s 1999 film, The Virgin Suicides, which collapses the glamour of youth into the melancholy of unfulfilled desires. The film’s eroticism is not overt but rather saturated with a hauntingly beautiful quality, capturing the transient nature of adolescent longing.

Similar to Coppola, Gu explores the tragedy of existing in the tension between purity of innocence and the seductive pull of the unknown, “Teenagehood is difficult, there’s a lot of instability. Where I grew up (Nanjing, China), you weren’t allowed to have boyfriends; it was seen as a distraction from school. So, you would just daydream about love and romance.”

The visual poetry of Gu’s world mirrors the internal landscapes of the figures, where burgeoning sexuality is interwoven with an omnipresent void. The subjects often appear in intimate moments—enjoying a cigarette in the nude, staring at the sky, or in a romantic “69” embrace—inviting viewers to ponder their mysteries. Our voyeurism is welcome, and the figures evoke both philosophical and sensual contemplation. Each pearlescent brush gesture is loaded with unspoken emotion. It’s a coquettish aesthetic that lingers in the mind, much like the bittersweet memories of a first love.

During our conversation, Gu walks me through the plot of Su Tong’s 2008 novel, Binu and the Great Wall: The Myth of Meng, a reimagining of the ancient Chinese legend of Meng Jiangnu. The story follows Binu, a young woman from a small village where women are forbidden to cry, employing sorcery to prevent their tears. Binu embarks on a perilous journey to find her husband, Qiliang, who has been conscripted to work on the Great Wall. The heroine is met with the devastating news of her husband’s death and her tears are finally released. Rumor has it that her tears flooded the surrounding village and brought down an entire section of the Great Wall.

Gu’s paintings are like echoes of heartbreak. The characters are phantoms of our hearts, figments of the mind, undefined, blurred, and infinite. When the stars whisper secrets to the night, do they mourn the lost dreams of forgotten lovers?

Xingzi’s upbringing in Nanjing, China is not forgotten by their New York-based practice. The traditional beliefs and the remnants of past political corruption of Nanjing make for a dynamic societal tapestry. Gu’s paintings, with their ethereal quality, navigate these complexities by offering an escape into a world where emotions can be tenderly and openly expressed. The figures in their paintings challenge conservative norms and highlight the often hidden dimensions of humanity.

“There’s sadness in looking back at childhood and adolescence, thinking about what went wrong and what could’ve been better,” Gu reflects on how undertones of melancholy or memory play into their paintings. Their work can be seen as a subtle critique of the rigid societal structures that suppress individuality and emotional freedom. By blending sexually charged scenes with a profound emptiness, Gu invites us to consider the delicate dance between public conformity and private desires.

Gu introduces a unique fusion of soft-hyper pop visual aesthetics within the confines of the white cube. Beyond that, Gu’s art transcends mere aesthetics and becomes a conduit for introspection, healing, and connection. As they unveil an obscurely vulnerable world, viewers are invited on the journey, delving into the depths of their own desires. “My art is therapy,” Gu shares, expressing the integral role painting plays in their life—a practice through which their inner child finds expression and solace.

As Gu contemplates their legacy, they recognise an earnest love affair. “It’s a challenging path,” they acknowledge, “but I’m in love with painting.” By the breath of this romance, we glimpse Xingzi Gu’s artistic ethos—an amorous commitment to the self, strangers, lovers and their unspoken affinities.

Written by Gwyneth Giller