Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

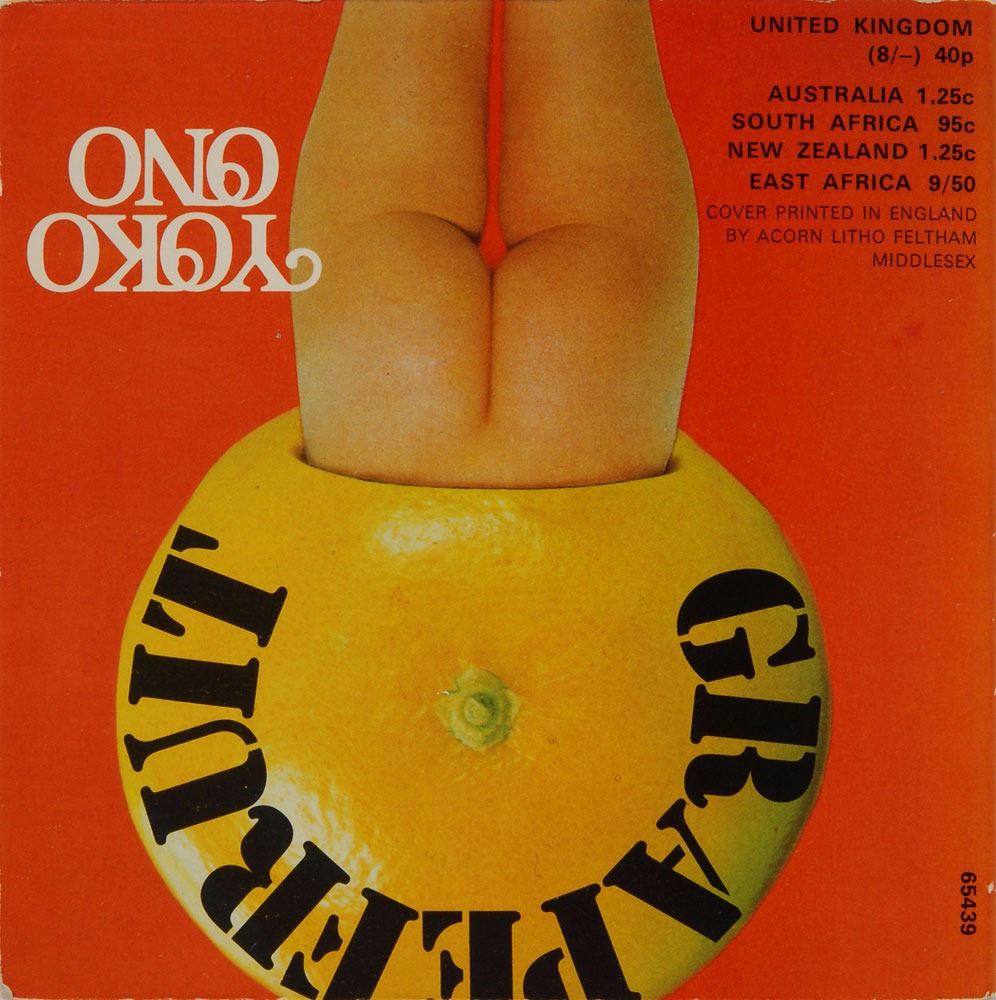

The colour of the book caught my eye: shiny and orange, the colour of sugary juice or of marigolds. I was returning a stack of books to the Rare Books room at the National Poetry Library in London, where I worked at the time. All was quiet except for the hum of the air-conditioning unit. I reached up to hold the small object in my hands, cradling it gently so as not to put pressure on the spine. The pocket-sized book was square, at least two hundred pages thick, shaped almost like a cube. On the cover, a fluorescent image of a grapefruit. The thin pages smelled like dust. Scattered across the pages were sparse lines of brief, surreal instructions for the reader. From “TWO SNOW PIECES”, for example:

No.1

Watch snow fall until dinnertime.

No. 2

Watch snow fall until it covers thirty-three buildings.

The artist and activist Yoko Ono published Grapefruit under her own publishing imprint, Wunternaum Press, in Tokyo in 1964. 500 copies were printed and the artist sold them for three dollars each pre-publication, six dollars afterwards. The original edition was bilingual, with English and Japanese side by side, and a sparse cover with only the word “Grapefruit” scrawled in handwriting on the side A compilation of miniature “event scores” created by the artist throughout the 1960s, Grapefruit reads like a script for a series of imaginary art pieces. With Grapefruit, Yoko Ono translated her art into the affordable, portable form of the book. Grapefruit blurs the boundaries between artist’s book, conceptual art, and poetry.

After my moment of discovery I returned the book back to its cabinet but went back to revisit it often. Each time, I discovered something new. How each piece on its own is like a small, floating piece of sky, and how all the pieces together work like a joyful imaginary language consisting mainly of clouds and snow. The poetics of Grapefruit is that of slow, tender attention.

“All the pieces together work like a joyful imaginary language consisting mainly of clouds and snow”

Yoko Ono’s recent works have often required this same close, tender attention from the viewer. With My Mommy Is Beautiful (2017), Ono invited visitors to write down a memory of their mother and stick it to the gallery wall, creating a collaborative, living archive. And in her ongoing installation series Wish Tree, Ono draws on her childhood memory of visiting temples and shrines in Japan; Ono chooses a tree native to the site itself and asks viewers to write down a wish and tie it to the tree. Similarly in Grapefruit, the artist speaks to us directly, inviting us into her space and into her world:

EARTH PIECE

Listen to the sound of the earth turning.

I made my first zine when I was 21, in the middle of my Masters degree in Creative Writing in my hometown of Wellington, New Zealand. I secretly printed out ten double-sided copies in the printing room of the creative writing department, stapling them down the middle using the zinemaking ‘eraser trick’ which often results in a broken stapler. You place an eraser beneath the spine of your booklet, open a stapler until it’s flat, staple the pages by pressing into the eraser, then use the end of a pencil to flatten the staple. I had copied and pasted ten poems and inserted a photograph of an empty stairwell that I’d taken years before on a digital camera, and switched to black-and-white using Microsoft Word’s picture filters. It was called (auto)biography of a ghost.

I was bored of waiting for someone else’s permission to see my work published. I was tired of sticking to boundaries drawn by genre and literary form, which to me felt arbitrary, constraining. I was impatient and in too much of a rush to write poetry. But I’d learned from other zinemakers, especially the New Zealand artist Kerry Ann Lee, that zines are by their very nature imperfect, unfinished, rebellious. With zinemaking, I could be in control of putting my own work out into the world. I could create a physical object—a poem, a booklet—that hadn’t existed in the world before, using only paper and staples and laserjet ink.

Later, when I moved to Shanghai on a scholarship to study Mandarin for a year, I spent evenings at the print shop on campus, counting out coins to print off colour copies of a mini zine about noodles. Since then, zinemaking has evolved for me. It used to be something of an irreverent fuck-you to the literary establishment; now it’s more of a practice of slow, careful making. Like essay writing, zinemaking is my way of working through whatever subject I’m obsessed with. It’s a way of asking questions, testing boundaries and sharing work still in progress. I’ve made zines about oranges, whales, mountains, ghosts, and I’ve made a zine about zines.

I am of mixed-race heritage: my father is white and my mother is Malaysian-Chinese. In my family, who are scattered all around the world, we speak English, Hakka, Cantonese and Mandarin, though my relationships to all of these languages is complicated, always shifting. It was only a few years ago that I first encountered books and artworks by mixed-race, diaspora women like me. When I looked deep into the archive, in search of a lineage of zinemakers and book artists who came long before me, it wasn’t easy to find any multiracial, multilingual artistic foremothers.

Archives and the buildings that house them are political. Collected and catalogued objects become part of an official cultural record, while those that don’t may be lost, forgotten. Zines and objects like Grapefruit resist categorisation and cataloguing, and this is why I’ve always been drawn to them. Ono picked the title because she wanted the name of a hybrid fruit to suit her hybrid work.

“Zinemaking has evolved for me. It used to be something of an irreverent fuck-you to the literary establishment”

Yoko Ono and I don’t share a similar heritage, but Grapefruit was the first artist’s book I found by an Asian woman artist created before I was alive. It was also one of few artist’s books by an Asian artist that I encountered at the National Poetry Library, which collects zines as well as rare artist’s books. Grapefruit set me off on a search for more. I found poet and artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s stitched books made of cloth, Indigo Som’s origami fortune teller, and actor Lucy Liu’s book sculptures and embroidery panels.

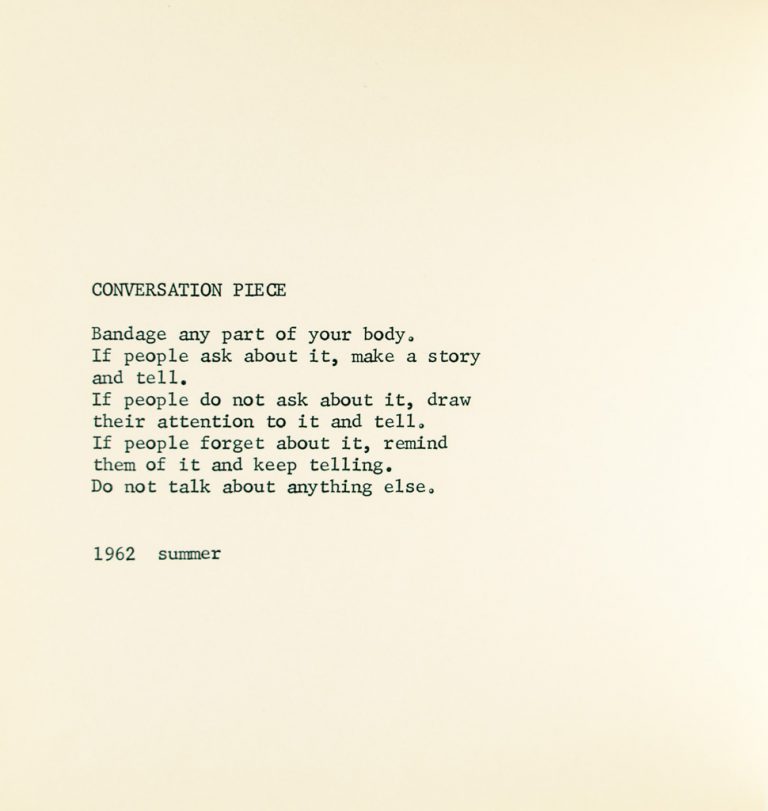

In “COLLECTING PIECE II”, Yoko Ono instructs:

Break a contemporary museum into pieces

with the means you have chosen. Collect

the pieces and put them together again

with glue.

Grapefruit helped me see the book form as flexible, experimental, full of radical possibilities. It helped me see myself as an artist and maker who can move freely between art forms, as Theresa Hak Kyung Cha did, and as Yoko Ono still does.

The dusty copy of Grapefruit and the quiet archive where I discovered it now feels like a dream, shut away in an empty library that’s been closed for many months under lockdown. But of course, it’s still real. The book had been there all along, even if no one had touched it for a decade before I did. I can’t hold it in my hands now, but I can describe it from memory. I can collect the pieces and put them together again, with a stapler and a needle and thread.

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to pitches@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”