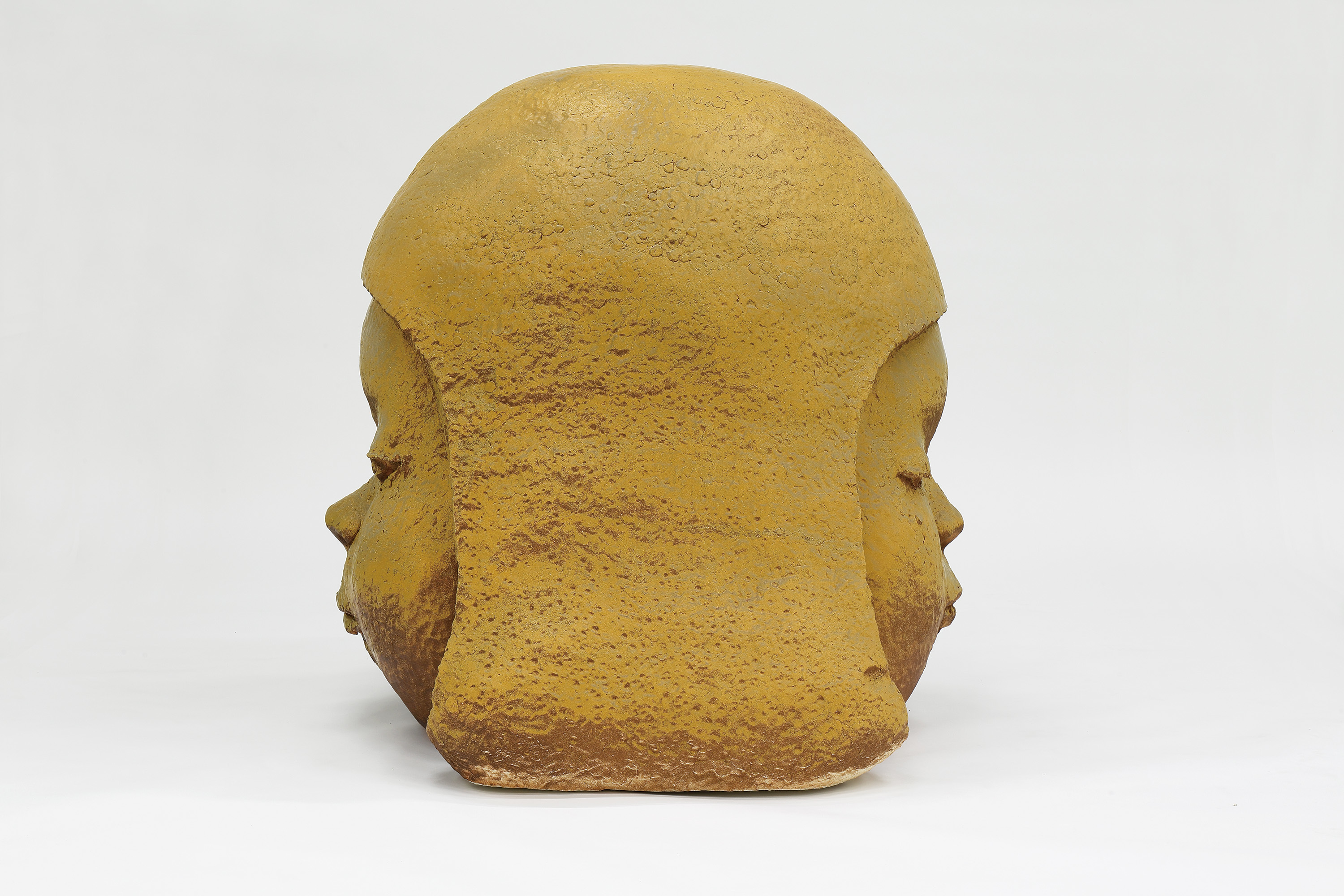

Miss Tannenbaum, 2018

Yoshitomo Nara loves mountains—a lingering fixation stemming from his birthplace in mountainous northern Japan. But it is at his own gallery space, N’s YARD in Nasushiobara, where I meet with the artist after an hour-long train ride from Tokyo back in April.

Built with locally sourced materials, N’s YARD is cradled by beautiful trees that are beginning to show signs of life after a long winter. It all conjures an unforgettably peaceful atmosphere in which to meet the artist and view his exhibition together. Nara’s sculptures, paintings and drawings are presented side by side with personal objects such as record covers and works produced by colleagues and friends; conceived as a window into the artist’s studio, it is a space meant for discovery and reflection. He shows me round, and we eventually settle to discuss his work.

Why did you decide to open N’s YARD?

Initially, I considered the possibility of opening my studio to the general public but that was not feasible for a series of reasons. So I then developed the idea of opening a separate space dedicated to my work. At first I considered refurbishing an old local schoolhouse, but the building was in too shoddy a state to safely restore. Finally, I decided to go ahead with an entirely new building, a place that someone else could easily run and manage financially when I will eventually pass away.

How have your childhood experiences influenced your art?

I was born in Hirosaki in the Aomori prefecture in northern Japan: a region geographically and culturally distant from the centre of power. The area is even less developed than other remote regions due to an unequal distribution of resources from the Japanese government. As a child, I remember being very aware of the existence of nuclear plants in my region that will indeed serve the purpose of cities such as Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka, and that this nuclear waste could be delivered back to my region again. At high school, I used to independently research the topic. I noticed that there was a clear intention of dissociating the negativity linked to the atomic bomb from the use of nuclear power to rebuild and develop Japan after the war.

When the Three Mile Island

accident happened in Pennsylvania in 1979, it deepened my activism against nuclear energy. The relevance of my “no nuclear” activism has been present in my work since the mid-1990s, years ahead of the Chernobyl accident and the more recent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan.

How did you become established on an international level?

I just wanted to study; I didn’t have a strong desire to become an artist initially. My main motivation had always been to learn. I moved to Germany because I wanted to study more. When a gallerist from Cologne saw my work at the degree show of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, they offered me a show in their space. After that, all developed quickly internationally. But my daily life hasn’t changed since then, apart from relocating back to Japan. I live a normal life most of the time because I go unrecognized, except occasionally within art environments.

“My motivation comes from activities that have nothing to do with art”

How do you still find the motivation to make art?

I continue to make artworks but not just for the sake of making artworks, and new ideas come to me continuously. Nowadays my picture of the world is broader, and my focus on my work has become sharper. In regards to my motivation, it comes from activities that have nothing to do with art. I collaborate with small and remote communities replanting forests in Hokkaido. Right now my mind is occupied 10% by the art world and 90% by all the rest, but it all feeds back into my motivation as an artist and refreshes my ideas.

In terms of going physically to the studio to work, there hasn’t been a routine in recent years, nevertheless I think about new works all the time. I also spend a good amount of time doing residencies in small communities because that’s what matters most to me now. Recently I did a residency in a disused two-classroom school in a small village of about thirty inhabitants, in a remote part of Hokkaido. Something very special happened to me while I was there. One day everything was ready for me to start painting, but suddenly I didn’t feel like it anymore and I didn’t do it.

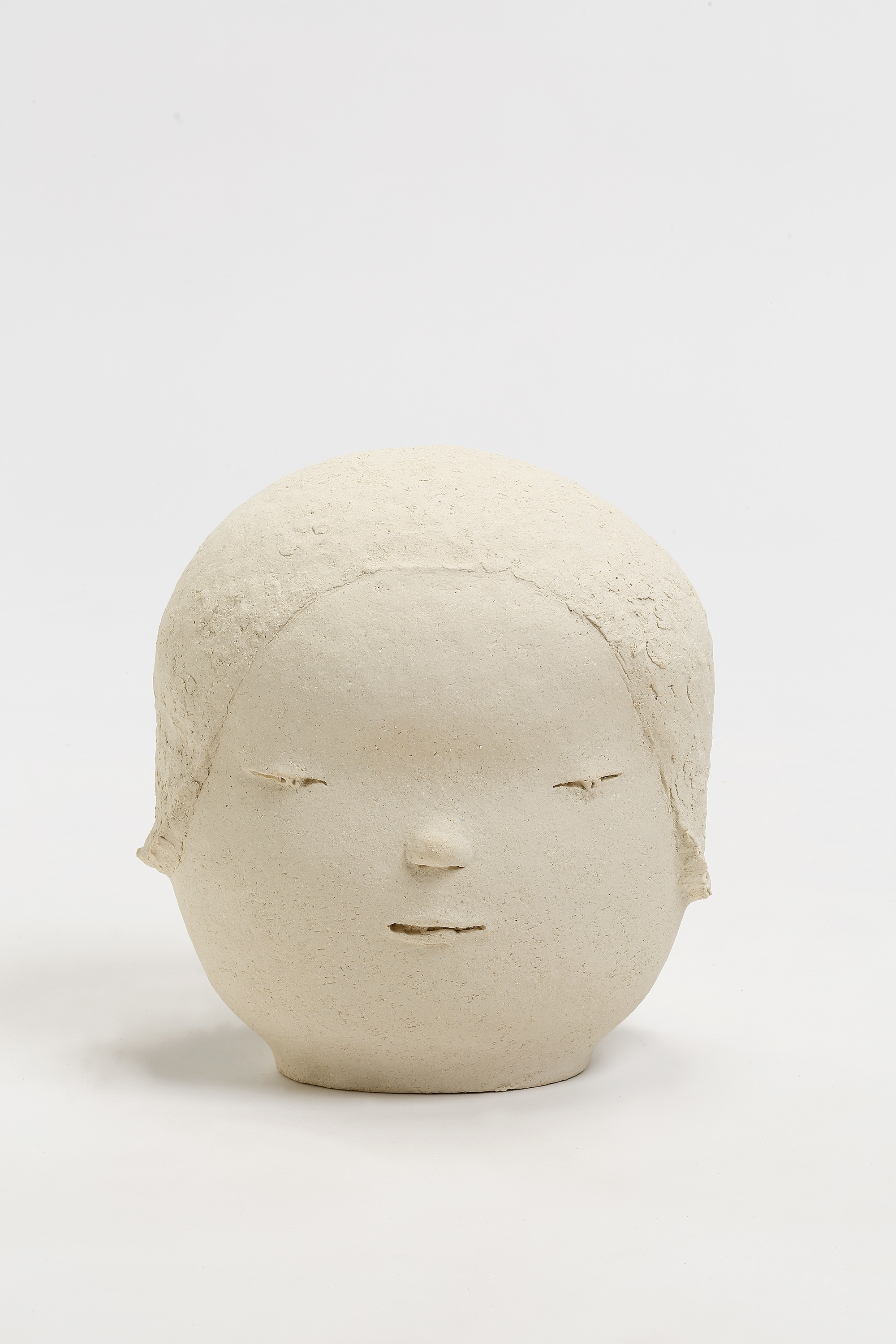

Because of the isolation and because I couldn’t work the same way as in my own studio, I spent a lot of time exploring the old school and found a dried lump of clay. While I was adding water to the clay, some children came in exploring and they started to collaborate with me very spontaneously to make the work. I was very inspired and moved to see children coming back to a disused school and gradually they worked with me on making the face of a child from the clay.

In that moment I felt a strong desire to make charcoal life drawings for the first time in thirty years, and I did five life drawings of the children—each 180cm in height. I wasn’t drawing from my imagination, as in my previous works.

The experience of that day has influenced hugely my latest practice, where the portraits of the children are more objective and the process resembles something similar to a child walking with a camera and taking pictures. The objectivity present in my latest work originates directly from my experiences within small and remote communities, and these sort of experiences are continuously feeding my motivation to make art and my ideas.