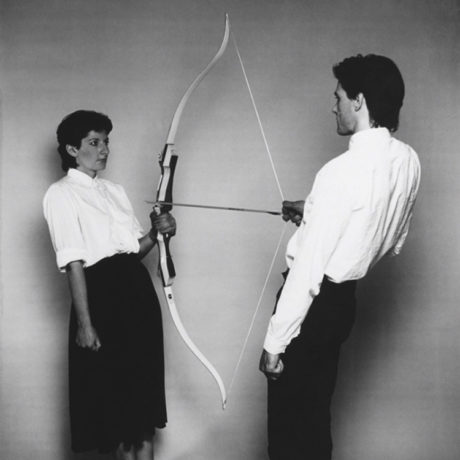

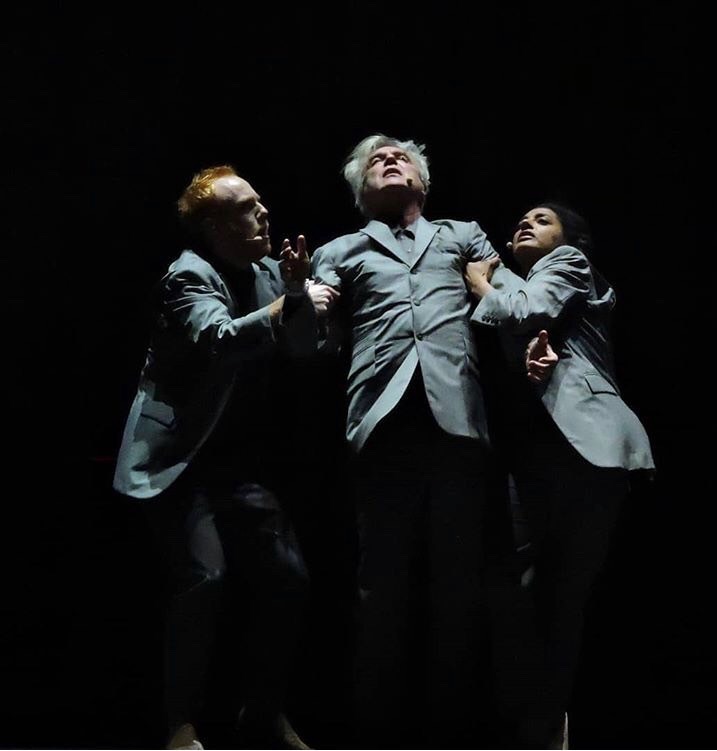

Renowned American choreographer Annie-B Parson has spent “many years kneading poetic structures into choreography,” collaborating with artists ranging from Salt-N-Pepa to Jonathan Demme and David Byrne.

Her artistry, particularly the work she creates with her company, Big Dance Theater, makes a conscious effort to embrace hybrid forms and explore fluid hierarchies within the company’s internal structure. Her choreography is both enigmatic and playful, and crucially, it focuses on work which rarely follows a neat linear narrative.

This crosses over into her writing. In her new book The Choreography of Everyday Life, Parson weaves musings on art, Greek tragedy, and dance into a supple stream of consciousness. The result is a series of oblique provocations rather than a staunch manifesto.

The Choreography of Everyday Life

is an often charming confluence of the grandiose and the mundane. At her best, Parson reframes banal encounters into beautiful, crystalline observations. When she sees a dog playing a game of catch with its owner, she is struck that they are dancing “a duet, [with] a perfect and pathetic duality between them, a game of synchronicity, agreement, and practice.”

“Parson weaves musings on art, Greek tragedy, and dance into a supple stream of consciousness, resulting in a series of oblique provocations”

Throughout Parson demonstrates a preoccupation with shapes, particularly spirals and circles. And indeed, there is rarely a direct line of thought from A to B in her writing. She takes deep pleasure in digression and doubling back. “Our lives don’t operate in a neat cause-and-effect structure,” she tells her husband.

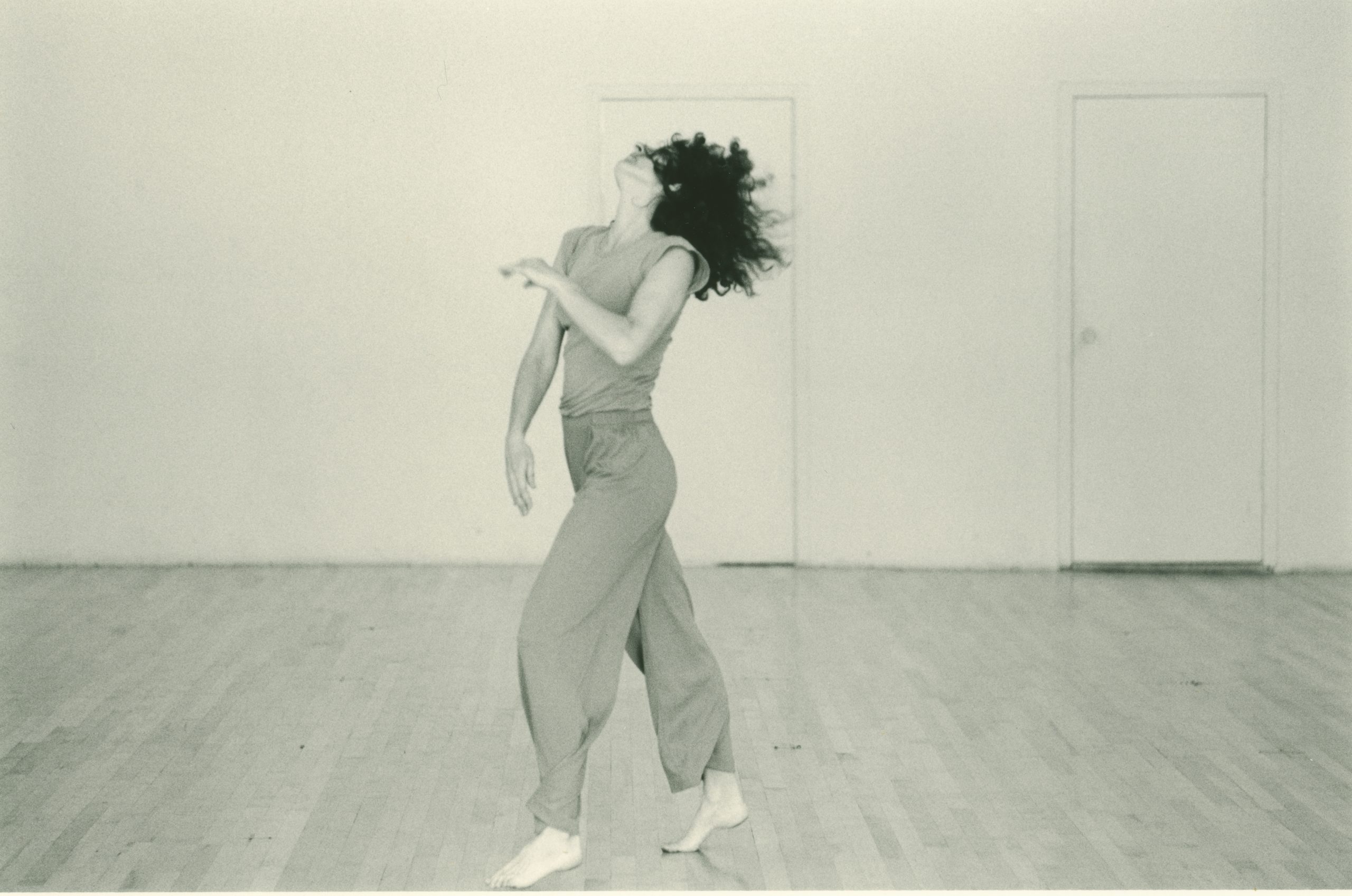

If Parson is advocating anything, it is fluidity in how one reads art and the wider world. She sidesteps linear narratives, claiming that “the day is non-hierarchically composed of light and weight, motion, space, shape, time, and sound.” Accordingly, the text slips from topic to topic, with no one subject having true priority over another: Parson’s writing extends from The Odyssey, which her husband and son discuss over a number of days, to the choreography of Trisha Brown, to the 2020 US election.

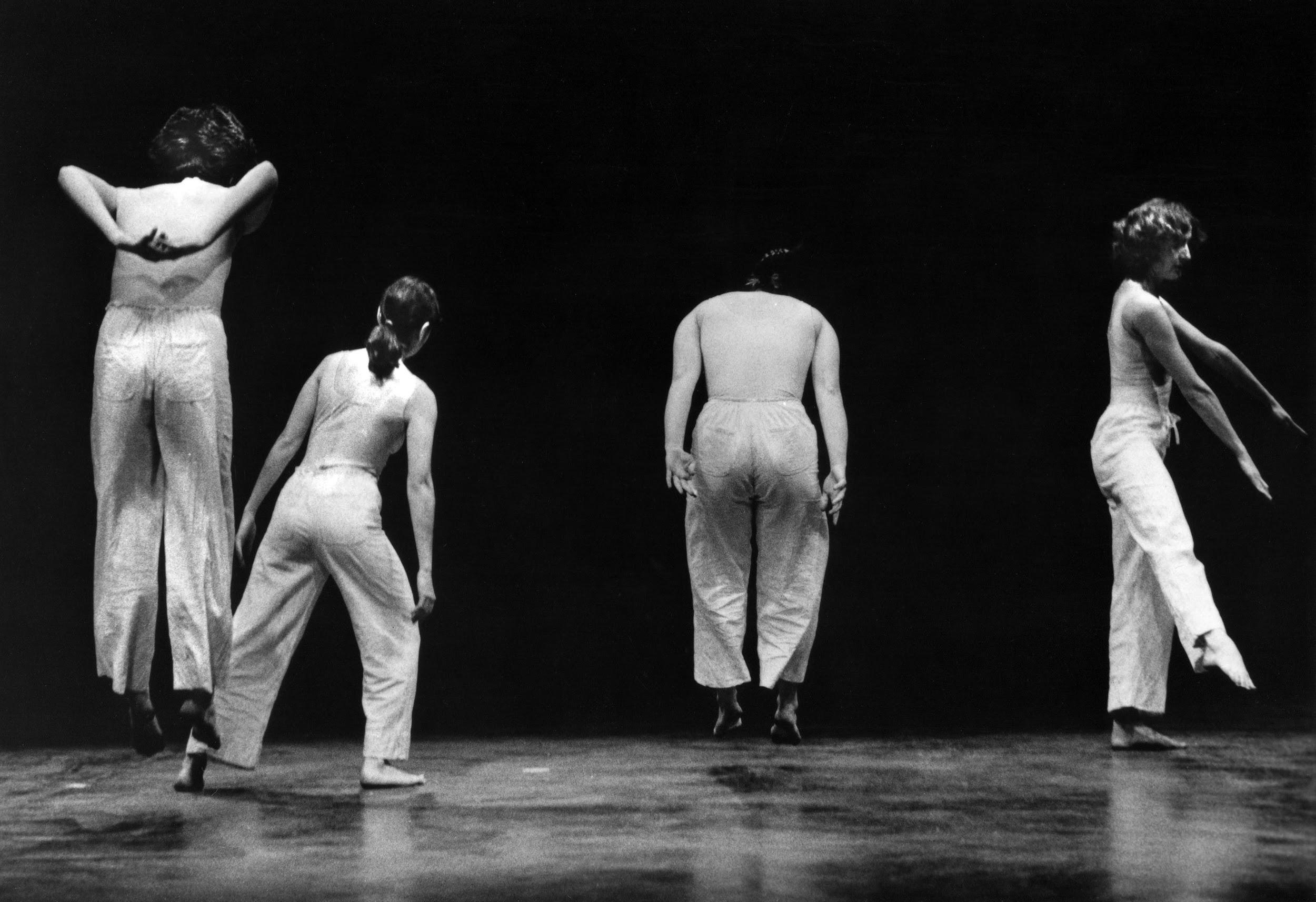

Parson relishes the discrepancies of her practice. Choreography, she suggests, is both innate and learned, natural and unnatural, organic and commodified. Selling dances “has always struck me as contradictory,” she writes. “The material, the stuff of dance, is the body… when people first danced, it was essentially a community in physical agreement executing poeticised, ritual actions in a circle.”

“Choreography, Parson suggests, is both innate and learned, natural and unnatural, organic and commodified”

Look carefully, she insists, and dance can be found in all of life’s small moments. She writes gracefully on how the “tempo and issues of space in navigating a public area” are essentially a choreographer’s concerns (pleasingly, this idea comes to her in a moment of brief irritation, when she has to walk behind a man talking loudly on his phone on a Brooklyn sidewalk). She likens someone dodging an uncomfortable question to the careful, contained steps of a square dance.

She insists that “nature uses complex formal spatial structures, and without knowing it, we are mirroring them as we move through the world.” Appropriately enough, the text is peppered with occasional, rhythmic line breaks, which create as much spatial awareness between paragraphs as there would be between dancers on a stage.

Some of the most broadly amusing moments come when Parson engages in droll critique of artistry and the art world. “Art comes from perception and craft plus a muscular imagination,” she writes, “all things unrelated to being a good person.”

She finds kinship in female artists: Louise Bourgeois for the way in which Bourgeois embraces the “droops…porous bulges…unsightly swellings and dripping sags” of female bodies; and Hilma af Klint, whom she admires for the way in which “she broke the form with her abstract large-scale paintings and created a tsunami”, while criticising public perception which views Af Klint primarily as a mystic, and not an artist. Ultimately, Parson comes to the pithy conclusion that, “regarding a MoMA retrospective, if you are a woman you need to be very old or dead, which is a safely unsexy and unchallenging persona.” It’s an entertaining and accurate observation, if a little slight.

Despite its wit and moments of profundity, there is an undeniable air of distance to Parson’s writing. She tends to observe from afar: her husband and son’s discussion about The Odyssey is mostly overheard and reported back, creating an undeniable sense of aloofness. For a piece of work that has such concern with the body’s movements, abilities, and cycles, this is precise, removed writing, and it can begin to feel somewhat antithetical.

Live performance, at its best, is a visceral art form, and one longs for something more corporeal to hang onto. For all its quiet beauty, this is a digressive and occasionally opaque piece of work. Parson skates over her ideas in pursuit of breadth, and the resultant effect is a ripple, rather than a tsunami.

Ava Wong Davies is a critic and playwright. Her latest play, GRACELAND, will premiere at the Royal Court Theatre in 2023

The Choreography of Everyday Life by Annie-B Parson is out on 11 October (Verso Books)