Confessions is a monthly column by Emily Pope. This week she speaks with Meera Shakti Osborne about her new show at Peer Gallery.

Lately, memories have been resurfacing with a ferocity that I wish would abate. In this conjuring, I am just another weird working-class kid wearing a weird bucket hat (which I thought would help me fit in in London – incorrect) getting on a 6 hour bus ride with my classmates for our year ten school trip to the Tate Modern. We saw Hitchcock’s The Birds for the first time, courtesy of our equally weird art teacher and a ropey vhs player, wall mounted on the bus. We got mildly pissed in the back seats on vodka and blackcurrant squash, whilst we watched Tippi Hendren get slowly pecked into a catatonic state. I remember going into the turbine hall and being totally overwhelmed. Moving through the galleries, I was completely terrified by Paul McCarthy and totally entranced by a painting of a somewhat abstracted forest, Gothic Landscape, by Lee Krasner, (1961). It was the first time I’d seen depression, or a specific kind of endless pain, expressed via an artform, and I cried.

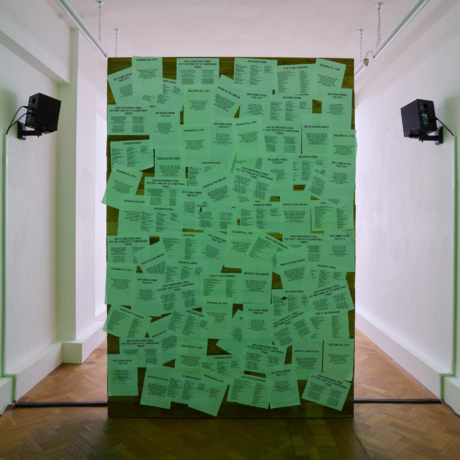

Thinking about the exhibition Hold Me Close (the forest is full of police) at Peer Gallery, by Meera Shakti Osborne prompted the above remembering for many reasons. The show, which collaboratively reimagines London as a forest, is the artist’s first major solo presentation following a residency at Peer. The work profoundly moved me, so I wanted to talk to Meera more about it. Their work moves simultaneously and poetically through youth work, zines, writing, painting, collaboration, community, installation and methods of sampling, but most crucially, there’s something in Meera’s work that is about redefining everything, constantly, by the terms of the people who live in the place the work is about, as opposed to by the authority that occupies it.

EP: What’s the story you’d like to tell me, something which changed the way you approach making work?

MSO: So I would say it’s not one specific thing, but it feels like a multitude of things, or a downward spiral – globally and happening in this country. I feel like as time goes on, things just feel more and more urgent. How is that reflected in my practice? I’m getting less and less concerned with the thing itself. I’ve always got one foot out of the door in the art world, and I think all sane people do. I actually wrote this text yesterday, and I started with a quote by Bayo Akomolafe, a Nigerian thinker and academic based in Chennai in India. He says times are urgent, we must slow down and I think my response to the downward spiral is a real desire in my practice to create or facilitate spaces where people can come together and feel safe or okay. Ish. And that is the goal in my work.

EP: That’s become such a rarity now. I think something that the art industry used to do perhaps even ten years ago (in a way that wasn’t terrible), was to offer a space for the weirdos of the world to unite and have a free evening with a free drink or free thing. All of that free stuff has dissipated! You’ve gotta pay at the bar now! Despite some people still making so much money, every time I see actual space being held for people to just have a chat, I’m like, oh that’s great!

MSO: You know, that is what it is for me, where I see my practice going. How can we, how can I, use all these resources that I see around me to facilitate spaces that make people just feel able to like, have a conversation or feel welcome. With the Peer show, I wanted certain people to feel welcome in the space. I wanted that to be explicit. I guess I thought about the gallery space as a resource. As a place where people can be inside. That’s a nice thing, that’s a special thing. And so how do you make that space? How do you bless that space as much as possible? Throughout the making of the show I was thinking about safety, who gets to feel safe in this city and who doesn’t.

EP: Could you tell me about the youth work you’ve done, how you work collaboratively with different groups to work on your exhibitions, how all of that links together?

MSO: I was a traditional youth worker in adventure playgrounds. Then I got my first grant from the mayor of London and started running my own projects with young people, often people from local schools, running projects with institutions. Then that developed into institutions coming to me to be like, can you run a project? I spent a lot of years working with institutions, running youth programs. The people that I’d work with would normally be the young people In the local area of the institution. I don’t ever cherry pick people. I’m quite open to whoever wants to work with me, but usually, I guess because of who I am, the institutions that approach me often are trying to work with marginalized, specific groups of young people.

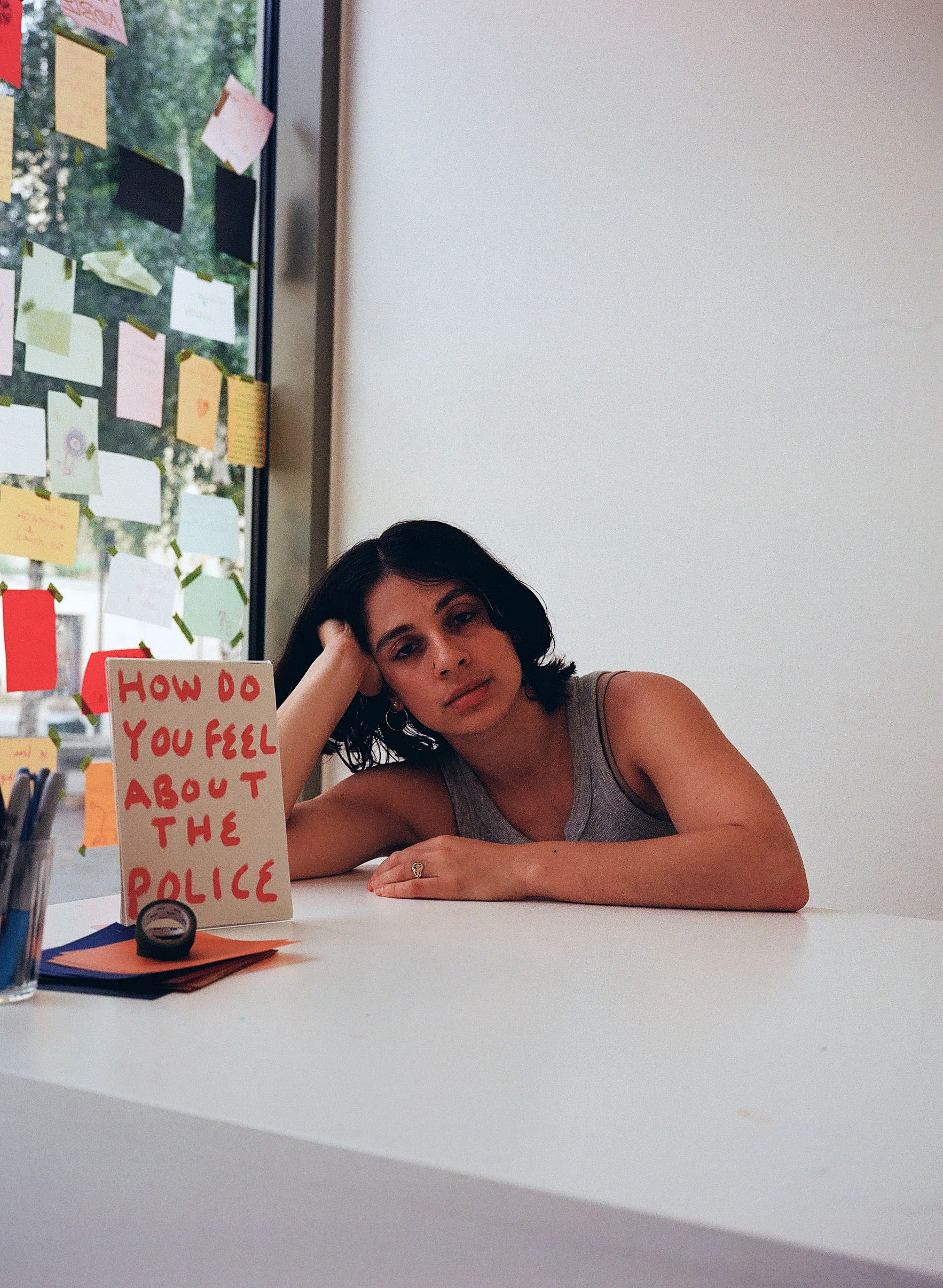

EP: Could you explain to me a bit more about radical safeguarding and why you want to use that in your artistic practice?

MSO: I’m in the process of developing a policy or access rider so that when institutions do come to me, I’m quite explicit about how I want to work and I want the institution to also commit to that type of working. A radical safeguarding approach to working with young people, firstly we shouldn’t call it radical. I don’t think it’s radical to not call the feds on kids. So traditional safeguarding, which you get training for if you’ve ever done youth work or worked with vulnerable people – often in the art world you actually don’t get any. So the safeguarding training that I got in the past is basically, if someone comes to you with some sort of thing which you find worrying or concerning, right, you report it to the safeguarding lead. And if you are the safeguarding lead, you then assess it. And you either report it to the social worker, or the police and often, the social worker reports it to the police. So the traditional form of safeguarding is very much an approach which takes away your responsibility from the situation. Radical safeguarding questions the idea that people need to be criminalized all the time. You are in a space with resources, think about what resources you have within that space. This type of safeguarding also asks you to question your judgements not as facts but as emotional responses. I guess one of the reasons why I wanted to adopt a radical safeguarding approach was because whilst I was working with Peer, October 7th happened and most of the people I was working with were Black and brown Muslim kids. I didn’t know how safe it was to talk about Palestine in that space. I was aware that in schools they were told not to talk about it. I think of spaces I’m working in as an in-between space from home and school, and for that to feel expansive and interesting and useful, I want to be able to talk about things without kids being criminalized.

EP: How do you feel about painting as a medium? Colour seems really crucial within this show, the red, the lilac are very striking – echoes of these colours are reflected in the hand written notes placed in the windows. Is that something that happens organically for you or do the colours have coded meanings?

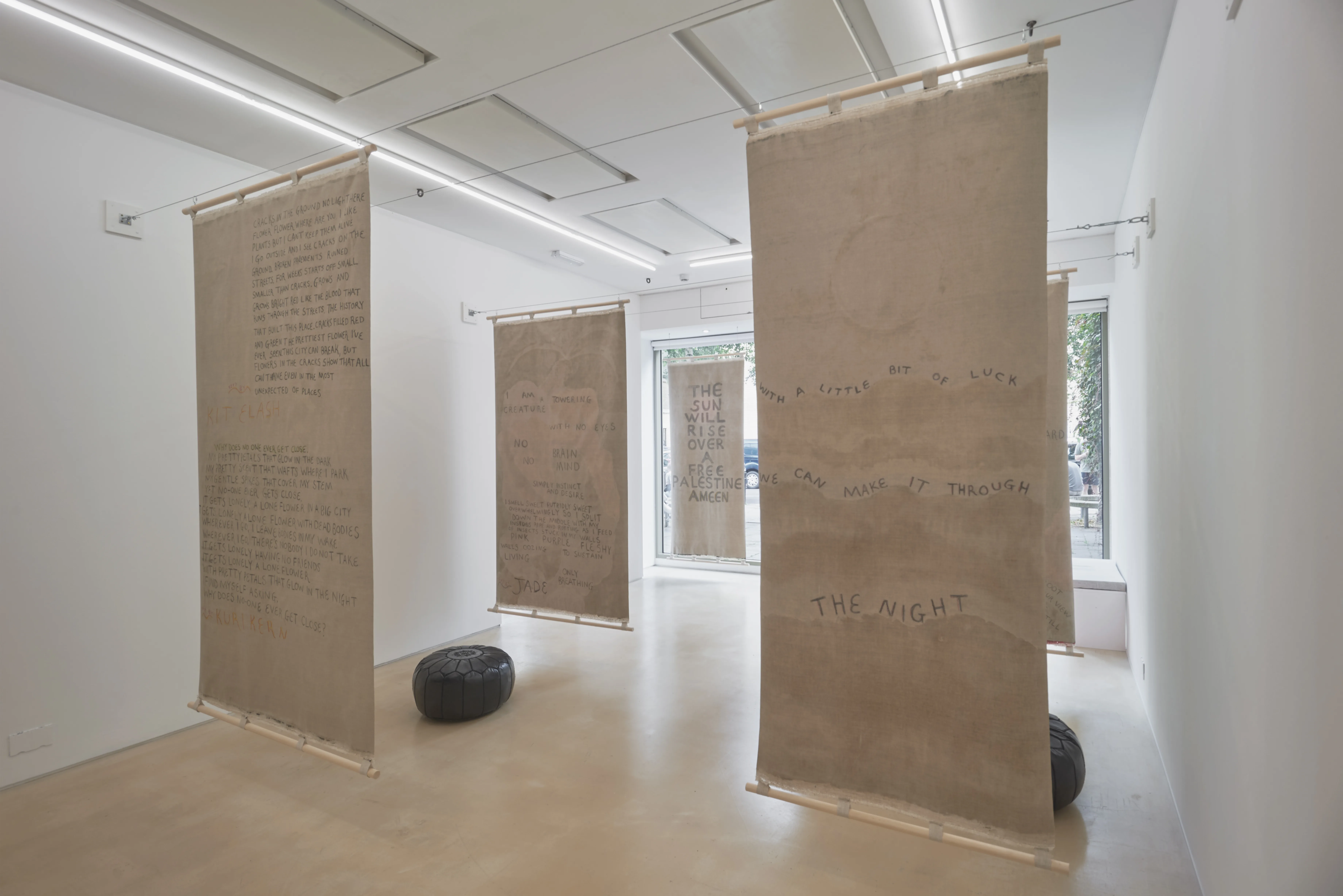

MSO: The way I paint is quite unique in relation to the rest of my work. I’m quite analytical, research heavy. For me, painting is a space where I don’t do that.That specific purple – it’s a city sky. There’s something so beautiful about it, but it’s so dreary. You know that purple night sky? It’s purple because of the light pollution. It’s so depressing, but also so beautiful. A lot of the city is like that. The red is like the blood of the city, the texts that the young people wrote – they were very emo and I wanted to reflect that as much as possible in the work. I wanted to also explore what a forest could be. Some of the colours are really not what you’d associate with the forest. Maybe there’s some green, but apart from that, I went for apocalyptic colours and colours you might find on a construction site.

EP: Could you tell me more about the text in the show? I’m specifically interested in how the text instructed the hanging paintings.

MSO: So the backs of the paintings in the show have text on them. The text was written by young people, their own reflections of the city but abstracted through forests/plants. I wanted the paintings to be paintings, but also hiding places. You can sit behind them, you can sit in between them, there’s these seats which you can move around. The space was a hiding place, because I think people should be allowed to hide! Young people should be allowed to hide. So yeah – I wanted people to be able to hide amongst the paintings.

EP: What do you think about the role of the artist within the community, or the relationship between the two? Do you believe that artists have a responsibility to work within the community?

MSO: I think if you don’t feel part of the community, you should leave the community alone. Or I think if you don’t feel part of the community, you should try and find your community. I guess I don’t think that is specific to being an artist. For me, being engaged and part of a community is quite central to making work. I want to make work about my friends and my community, for them and with them, they’re the audience for me. That’s who I think about and if I didn’t have a community, then I wouldn’t know who I was making work for. I don’t think that anyone should or shouldn’t work in a certain way. I don’t think that there’s more value in what I do than another way of working.

‘Hold Me Close (the forest is full of police)’ by Meera Shakti Osborne was exhibited until 31st August 2024 at Peer Gallery, London. View more of Meera’s work here.

Words by Emily Pope