What happens when you set out on a search for the brightest and best of the European art scene, sourced from sixteen countries? Metamorphosis: Art in Europe Now has been more than a year in the making, which is hardly surprising given its scope. Launched without a clear theme in mind, the uniting element is Europe itself, and open-ended proposals were submitted to the curatorial team from over 1000 artists. All were born between 1980 and 1994, and came of age after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Now, Europe stands on the pinnacle of another moment of radical transformation with Brexit fast approaching.

The exhibition’s title, Metaphorphosis, nods to the shifting, mutating borders that are at stake in the current political climate. The freedom of movement valued by young people throughout the EU has been drawn into question, and many of the artists featured at Fondation Cartier live in a country that is different to their place of birth. Their work reflects this fracturing, drawing on elements of collage, casting, ceramics and folkloric traditions.

Swedish artist Lap See Lam explores Stockholm’s Chinese restaurants in her dystopian video work, producing ragged digital scans of their interiors. For Hendrickje Schimmel (whose artistic practice is named Tenant of Culture), rucksacks and other discarded garments form the basis of her cut-up approach to the clothes that we wear, informed by her background in fashion design. For both artists, as well as the remaining twenty-one artists exhibiting, there is a preoccupation with cultural heritage and past legacies, considering how these identities can be transformed and taken up anew. Below, curator Thomas Delamarre opens up about his vision for the show.

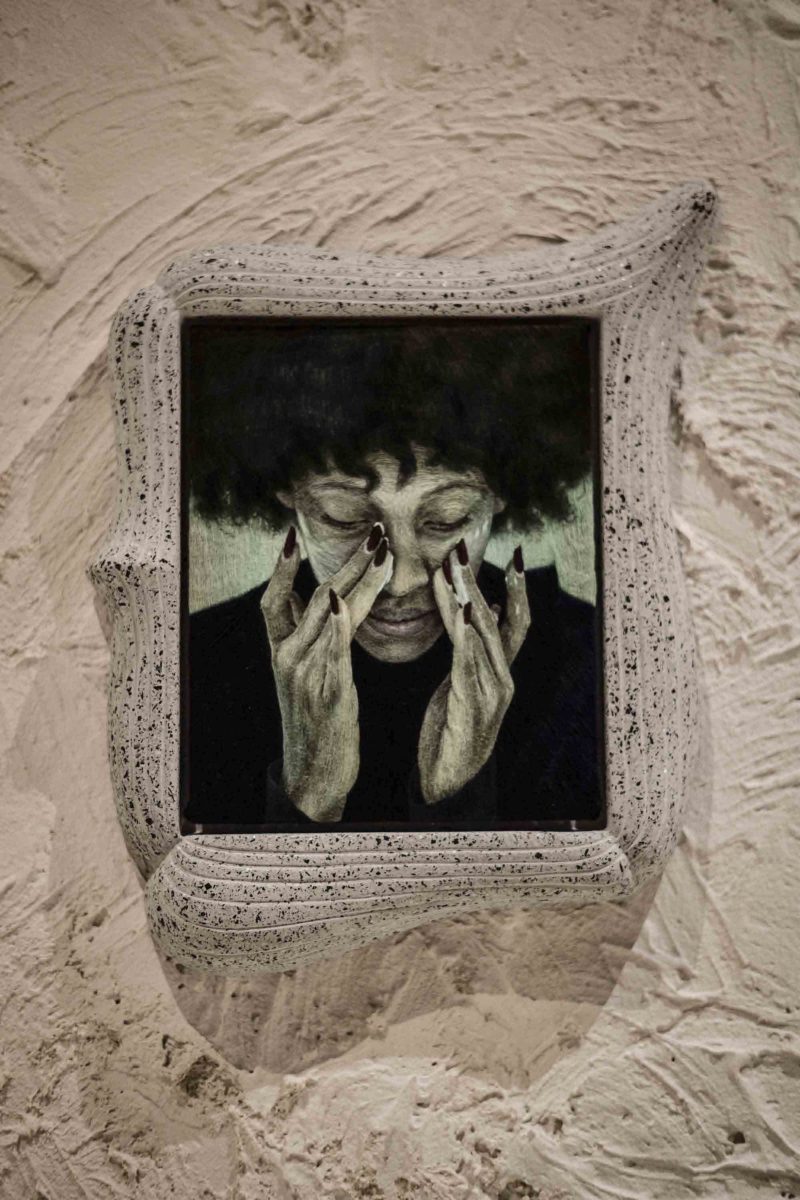

- Evgeny Antufiev

What was the process of putting this show together featuring artists from all over Europe, and why did you feel that the right moment for it was now?

One of the main motivations behind the show was that, as we all know, there are many questions and concerns about the state of Europe right now—on its identity and on how we live together in this territory. Beyond these concerns and the criticisms being levelled at it, we wanted to show that, yes, there are some dark questions, but there is also an incredible vitality to the European artistic scene—and especially the young artistic scene. The young generation’s power is that they know they are the ones who will be responsible for Europe for the next decades, and they are really taking the subject into their hands and exchanging and discussing together from one country to another.

We wanted to focus on this young generation born in the eighties and nineties, the first generation that grew up after the fall of the Berlin Wall, who became teenagers or were only just born when Europe started to look like it does now. They grew up knowing a more open territory, where mobility was different and renewed, and indeed half of the artists who are in the show live in a country that is different from their country of origin; there is a real mobility happening. It doesn’t make the other concerns disappear, but it means that there is still hope.

How did you go about finding the artists to include in the show?

The first decision was to travel. We didn’t want to build this show out of receiving portfolios; it didn’t make any sense because the idea was really to understand what is happening in Europe right now, so we wanted to go in the cities and to meet with the artistic scene. We met with artists, but also with the independent art spaces and the curators—everything and everyone that makes an artistic scene. We have travelled through twenty-nine countries for the past year, since early 2018. We would sort of scan the artistic scene, building a list of exhibitions and of awards for local young artists, and then decide which artists we really wanted to meet. And then, of course, when you’re in the country, you get recommendations too; that’s how we shaped the research.

“The young generation’s power is that they know they are the ones who will be responsible for Europe for the next decades”

Some common threads began to appear from one practice to another, which we sum up in the title of the exhibition, Metamorphoses. Notions like collecting, recycling, transforming; archeology; reusing objects, elements and narratives from the past—almost like in music, where you are assembling, mixing and remixing. It ends up with very different aesthetics or practices, but still there is this common idea of metamorphoses, of transformation of shape. It’s through these practices that the artists give an echo to some very major issues that are not strictly European but affect the whole world. The question of recycling materials, of re-reading important historical narratives and the history of art. And also a notion of hybridization that we are seeing i many of the paintings and sculptures, the idea of fluid identity.

It’s interesting to consider this layering and referencing of the past in the show, which I feel in the last five years was often bound up with a sense of irony. The artists featured here appear to be more serious and hopeful about the future. How does the show reflect this shift in attitude?

It’s very true, there’s much less irony now. I have never really favoured this way of engaging with the world. It’s less present these days, maybe because the issues have become more pressing. Here, it doesn’t mean that the artists are super serious, just that they are looking at things from the same level as their subjects rather than looking from above. They are confronting issues directly, rolling up their sleeves and getting to work.

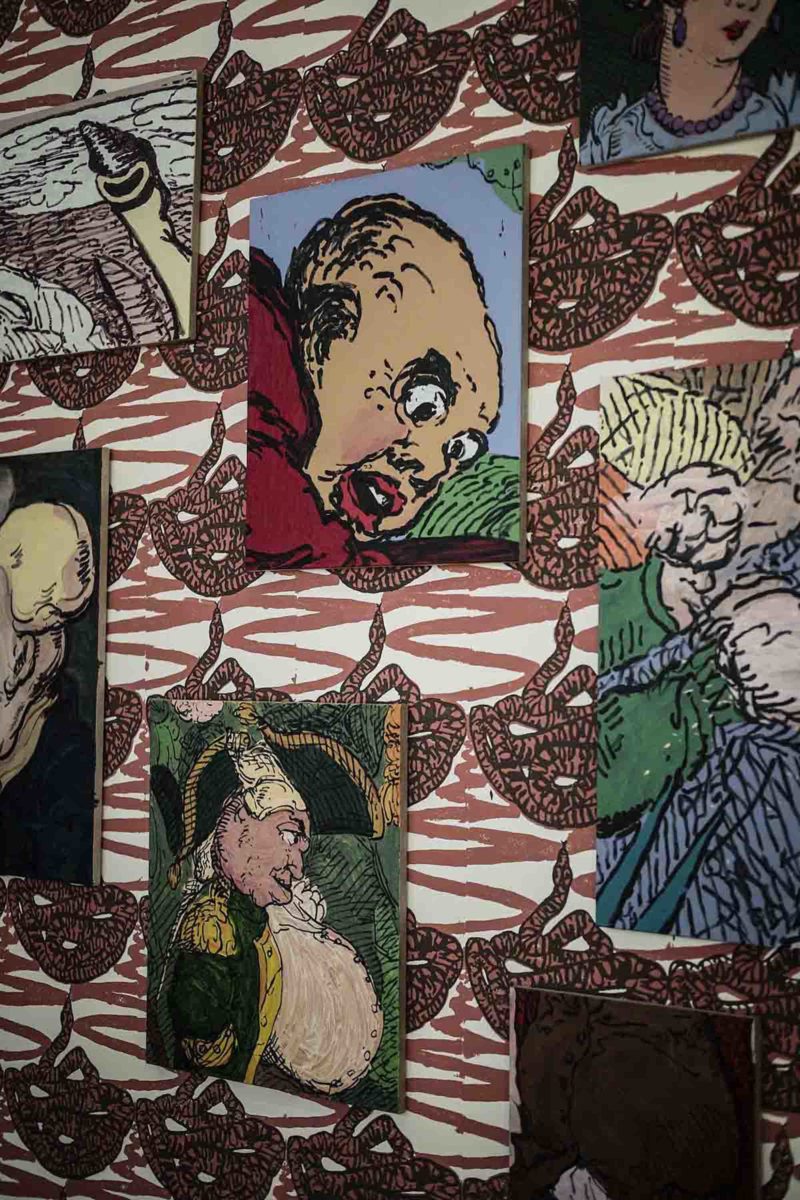

- Left: Marion Verboom; Right: Kasper Bosmans

“These artists are confronting issues directly, rolling up their sleeves and getting to work”

How did you make sure that you some of the underrepresented countries, particularly from Eastern Europe, were exhibited alongside those countries that receive more exposure in the art world? Did that balance of representation present a challenge for you in the curation?

That was one of the reasons why we knew we had to travel. At art fairs you really only see a few galleries and artists from Eastern Europe, and even in museums or art centres that is also often the case. Of course we see artists from Germany, Great Britain and a few other countries, but who sees artists from Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia or Moldova? There are still many countries that are almost as far away from us as Eastern Asia. Some people don’t even know that certain countries exist in Europe, and I wasn’t very good at European geography when I started. I have a big map in my office now.

Are you worried about the future of Europe?

Yes I am. Who wouldn’t be worrying? I’m concerned, but I feel that this crisis has brought everybody—not just the young people—to think more about Europe, which was not the case before. Everybody now thinks about how they position themselves in relation to the European identity. It happened for me, and there are so many interesting initiatives from this young generation, who are really trying to think about their future together. So I’m worried but, as in many crisis situations, I think believe there will be a strong reaction. I am still optimistic.

All photographs © Edouard Caupeil and Thibaut Voisin