Hidden in plain sight, there’s something insidious about monuments. Familiarity and their positioning on the streets, where they blend with buildings, stone on stone, means that we don’t always see them. They’re stitched into the texture of daily life, a heavily loaded backdrop to our conversations and commutes.

The paradoxically inconspicuous nature of many monuments has left them standing year after year, slipping through cracks and dodging issues of morality and ethics. But recent events have rubbed raw feelings of alienation and pumped-up partisan fervour, all of which has sparked a long-overdue reassessment.

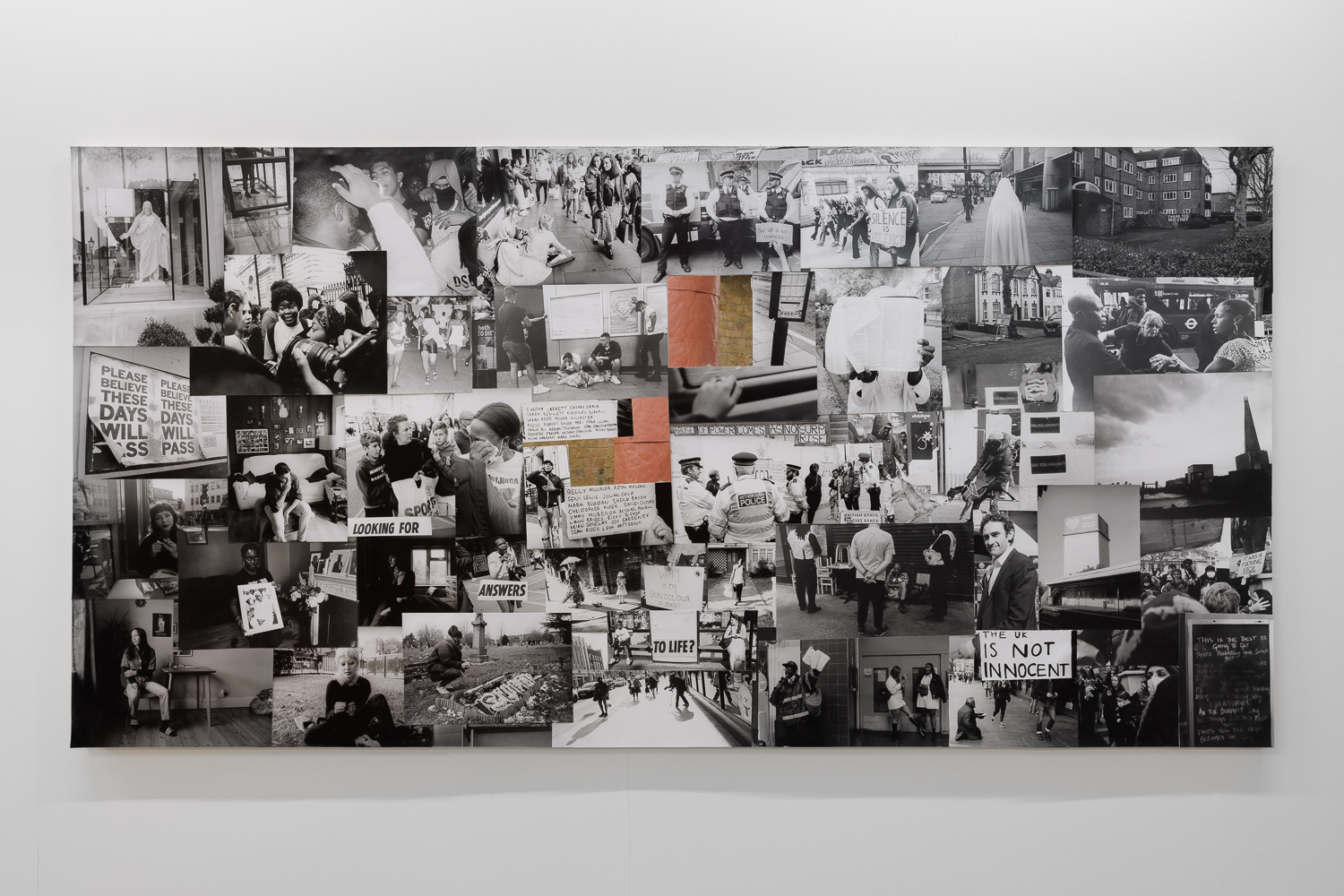

What makes a monument? It’s a question that 46 artists based or born in the UK have been grappling with in the run up to Testament, a timely exhibition at Goldsmiths CCA. The show is a response to discussions around the pandemic, Black Lives Matter, the climate crisis, and Brexit.

Each artist has been invited to make a proposal that considers the role of monuments, whose stories they preserve and whose they exclude, and whether there’s room for monuments to be reimagined. “Some could in theory exist in a park in three weeks; others might be physically possible but financially impossible; and then there are pieces that defy the laws of physics,” says director Sarah McCrory. The tone varies from funny to tender to tragic.

Adham Faramawy, an artist of Egyptian descent who grew up in London, has always felt uncomfortable with the monuments in the UK capital, especially those around the seats of power: “The monuments to military figures and slave owners and colonial figureheads,” they say. “I’m here because of colonial histories, so I’ve always thought, these aren’t for me. They’re something to be aware of, but they don’t serve me or any of the communities I’m a part of.”

“The danger with more traditional monuments is their permanence. Where is the space for changing our minds?”

They explore the experience of the migrant community by way of metaphor in A Proposal for a Parakeet’s Garden

, a film about the contentious presence of parakeets in the UK and the suggestion that they’re invasive, costly and feral.

Faramawy wants to shift the focus away from the physical nature of monuments and towards the resources spent on them, which is why they’ve chosen not to make a maquette for a garden. With their proposal, they aim to start a conversation and to encourage people to donate to local charities that support migrants and refugees.

“If there’s enough money for this kind of behaviour, the marking of events and histories, and we’re living under a government that’s taking resources away from people, what do we do?” they ask. “Do we stand by and keep making bronze and stone sculptures, or do we help out?” It’s a point that brings to mind Maggi Hambling’s divisive nude sculpture ‘for’ Mary Wollstonecraft, which was unveiled in north London in November 2020 after a 10-year community campaign to raise £143,000.

The Colombian artist Oscar Murillo also feels firmly disconnected from monuments in the UK. “I live here, but I have to think back to coming from Colombia to really engage with the subject from an emotive point of view,” he says.

Murillo grew up in a village whose founder, a plantation owner, is memorialised in the form of a bronze bust in the main square. “When I talk to my friends about it, they ask, ‘Why don’t you guys come together and bring it down?’ And I could, but rest assured, if I were to do that at two o’clock in the morning, by four o’clock the guys who work in the sugar fields would be in that same square waiting for a bus to take them to work.”

“Do we stand by and keep making bronze and stone sculptures, or do we help out?”

For Murillo, removing a monument does not erase the far-reaching impacts of those who it memorialises. The past is never far out of sight in the present, nor in the future.

It’s impossible to talk about the installation of monuments now without also discussing their removal, especially since the toppling of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol in 2020 and the ongoing debates about civil war general Robert E Lee in the US. It seems common sense that if something is offensive to a significant group of people it shouldn’t be present on the street.

As to whether they should be tossed away without a trace, or dumped in a nearby harbour, McCrory has the appealing idea of taking all the out-of-date objects and planting them in a field somewhere. That sort of graveyard would historicise problematic public art of the past and give it appropriate context so that we understand this isn’t who we are anymore.

“For Murillo, removing a monument does not erase the far-reaching impacts of those who it memorialises”

But as Murillo says, “Will that change anything? Perhaps, because it’s a catalyst. But I think it also requires an awareness, and I’m more concerned with the fact that, for example, the plantation culture is still alive and how we’re going to change that.” With his proposal, Collective conscience, he hopes to inspire a coming together of people and ideas. The installation comprises white plastic chairs evocative of family gatherings, disposable pieces of furniture that for Murillo serve as a reminder of “a spirit of living collectively which has been depleted.”

The danger with more traditional monuments is their permanence. “Where is the space for changing our minds?” asks Faramawy. “Where is the space for us to develop our ideas and our feelings about ourselves as a society and as a community? How do we do that when we’re working with objects made of metal and that don’t rot?” If the only answer to permanence is deconstruction, that lands us in another danger zone, one that’s oppositional and reactive.

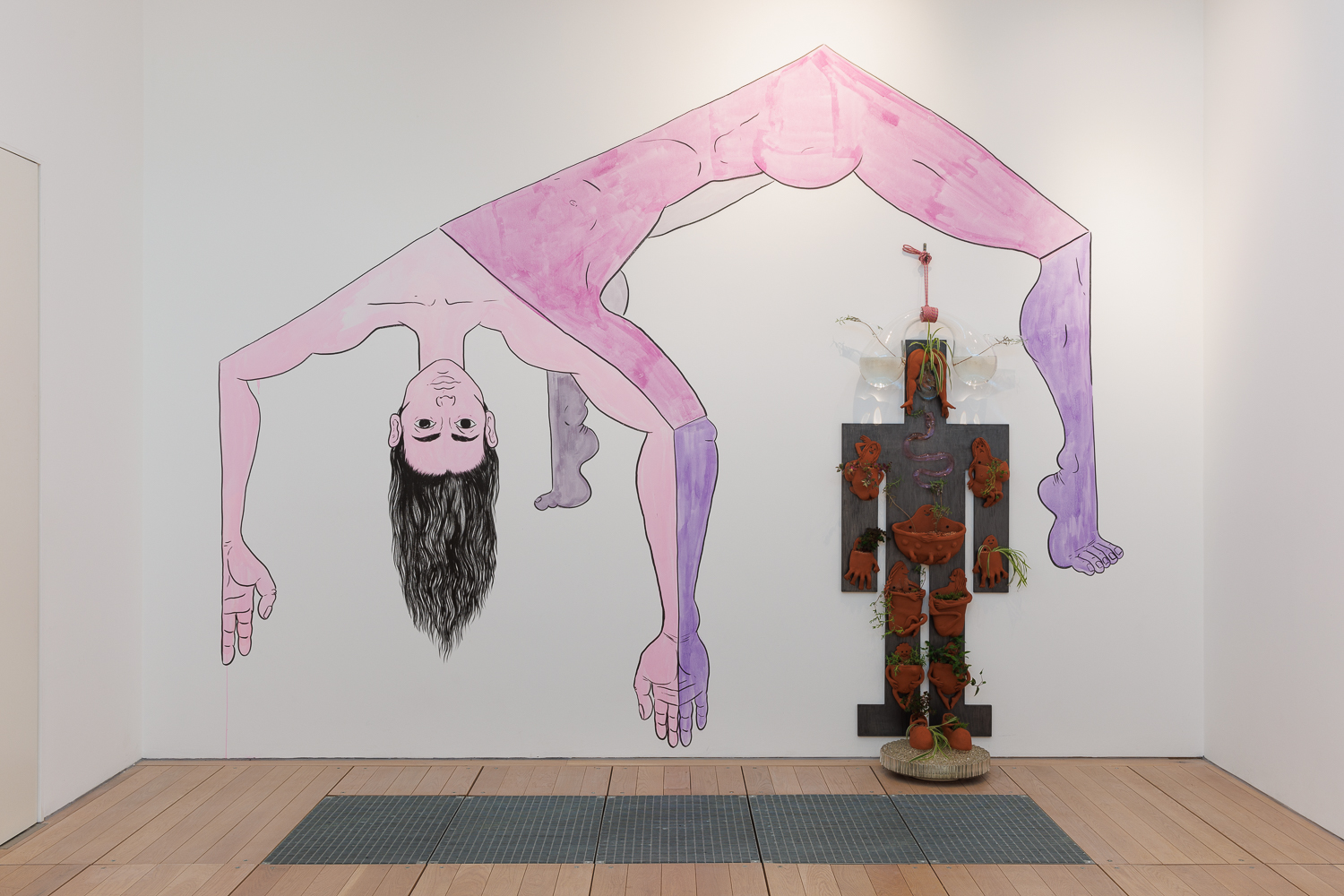

Ghislaine Leung is searching for an alternative. The London-based artist is known for playful concept-driven interventions, many of which are based on scores, or instructions. In her work, she’s interested not in permanence or reversibility, but in circulation. “I’m thinking about the life of something and of vulnerability as a mode of resilience,” she says.

“The more vulnerable my work is, the more resilient it becomes, rather than the other way round, when you try to fix it and literally make it the strongest, heaviest, biggest thing,” she explains. “Somehow that’s not resilient because it’s brittle and it can’t bend. It doesn’t move with life, it’s not active.”

Leung’s proposal is a blow-up pub that must be inflated to the maximum the space allows and displayed for the duration of the exhibition. Rather than a public artwork, it’s a space in which a public can be constituted. In other words, it’s about the people. For Leung, questions around monuments are centred on the public, not just as a social body but as a space, one that is increasingly being encroached on.

So, what makes a monument? It’s no single person’s place to decide who or what should be celebrated, and when and where. If one work at Goldsmiths CCA exemplifies this then it’s Irish artist Yuri Pattison’s decommissioned border force immigration and passport control desk, which once stood at Heathrow.

It’s a stark, solid piece of furniture, literally monumental, yet if you were travelling as a privileged citizen of the country to which you were returning, you probably wouldn’t pay much attention to it. For others, though, it represents something completely different, entwined with invention and history and power. Something that asks questions rather than answering them.

Maybe that should be the purpose of all monuments?

Installation photos by Rob Harris

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022