Zakia Sewell’s early memories of art will be familiar to many. Being “dragged” around a gallery speaks to an age where children cannot yet appreciate the work that they are shown, nor understand that access to culture is not universal. “I think my dad wanted me to do art,” the London-based artist remembers over a video call, recalling childhood hours wandering Parisian museums. “There was a bit of pressure to draw and to express myself visually, but I never really felt connected in that way.”

Sewell instead found her place in music, working as a radio producer, host and DJ. Her practice expands to include narrative storytelling, archival foraging and musical curation at the edges of media and traditions, from abstract expressionism to UK Garage

. Her description of a late-night editing session reflects her sprawling, multidisciplinary approach: “There’s always a logic, but really, it’s an unfolding,” she explains. “You have to work and deeply listen to what the audio is telling you, as opposed to the story that you thought you were going to tell.”

For nearly five years, Sewell has hosted Questing, a weekly jazz and soul show on London’s NTS radio. The pandemic stalled many of her live projects, but her Saturday morning slot easily adapted to a home broadcasting setup. The show has become something of a ritual for her. “I’m always conscious of the sounds and kinds of emotions I put out,” Sewell says. “If I start off with some dark melancholic music, I’ll always try to bring it to somewhere more positive towards the end.”

Each episode of Questing moves through a breadth of free and spiritual jazz, folk, dub, reggae and pop, with a focus on overlooked rather than new music. “It’s an intuitive exploration of different sounds that might not necessarily have a direct connection, but I sense something so put them alongside one another to make that known,” she says. Texan new-age artist JD Emmanuel is a favourite, as are jazz titans like Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane, while global sounds from Indian sitar to bossa nova feature regularly.

“You have to listen to what the audio is telling you, as opposed to the story that you thought you were going to tell”

Questing’s curatorial ethos is a product of a childhood surrounded by art and music. Sewell’s father Caspar, an amateur painter, played in folk bands while her mother Amey, of Carriacouan heritage, remains a soul singer and music enthusiast. Both laid the foundations for an upbringing defined by place and sound: Zakia remembers the omnipresent roar of planes from Heathrow airport as she grew up in Hounslow, West London, the silence of her father’s native Laugharne in south Wales all the more captivating for the contrast.

A stint at legendary Honest Jon’s record store on Portobello Road followed her time studying English at university, before she was introduced to London-based radio production company Falling Tree. Her partnership with producer Alan Hall forms the bedrock of My Albion (2020), a four-part narrative documentary for BBC Radio 4. Tracing the history of a semi-mythical Britain via folk music, iconography and ritual, My Albion epitomises Sewell’s interest in reconstituting identity via historical fragments, musical artefacts and psychological ephemera.

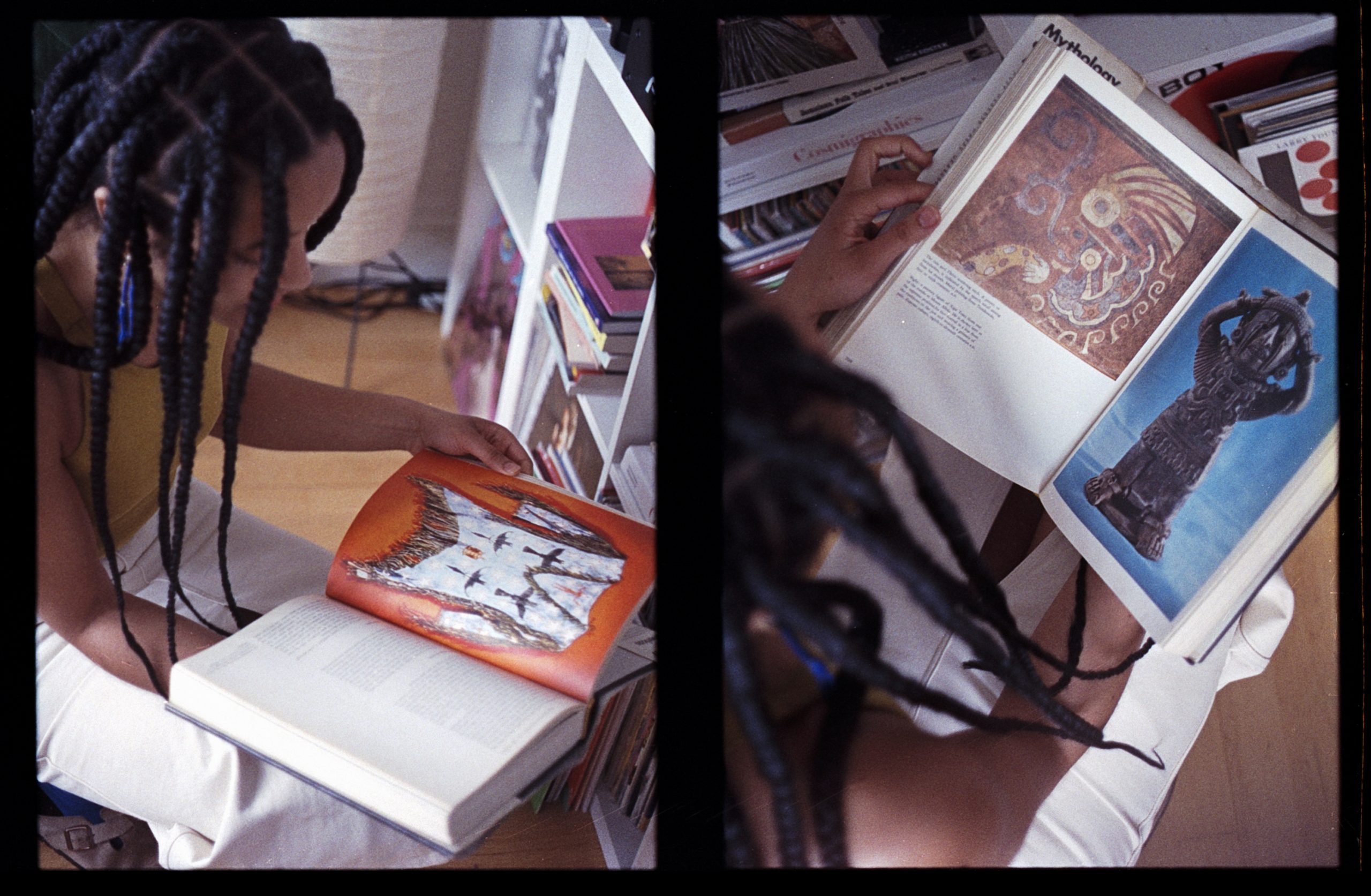

Zakia Sewell at home in London, 2021. Photographed by Caspar Swindells for Elephant

My Albion begins in Herefordshire in search of a sheela na gig, the figurative carvings of naked women common to Britain and Ireland. Across the series, music and art are tested as vehicles for memory via interviews with artists including Fern Thomas and Rabab Ghazoul. Connections with artefacts are direct, Sewell explains, whereas music is more slippery and therefore contested. “Songs accumulate the debris of human experience over time. You lose the precision of what that song meant to that first person, but you also have all this incredible bank of human experience that adds to it.”

Redirecting wider questions onto her guests while deftly shifting their context, Sewell strips her queries of their historical, often postcolonial contexts to invite new perspectives, while never completely retiring her own position. “As a mixed-race woman, does this music belong to me?” she wonders in the preface to the series. “Could Albion ever truly belong to someone like me?”

She asks a melodeon player of mixed Caribbean heritage whether he feels that traditional British folk music is his to claim: “I was expecting him to be a little tortured and conflicted about it,” Sewell admits. In reality, he believes the origin of these songs in his own British birthplace surpasses their colonial undertones, a perspective that Sewell nurtures from a distance over the four episodes. “It’s about getting out of the intellectual pondering and thinking about if music feels good,” she explains.

Sewell’s desire to reassemble disparate identities is rooted in her own past. She grew up apart from her mother, who began experiencing schizophrenia shortly after Sewell’s birth. “I was quite disconnected from my mum for a lot of my life, and that also meant being disconnected from my heritage, from my Blackness, from my Caribbean family,” she says. Conjuring “an idea of Carriacou as this kind of alternate landscape” in My Albion represents part of her ongoing attempt to reconcile her identity.

“Songs accumulate the debris of human experience over time”

This journey also motivated Radio 4 documentaries My Amey and Me (2020) and Big Drums on Little Carriacou (2018). In the latter, Zakia returned to her ancestral home to investigate dance rituals with slavery-era origins. My Amey and Me follows Zakia and her mother Amey as they unpick the past and move towards resolution.

When her mother first appeared on her radio show Questing in 2018, the pair laughed about the casual nature of their relationship, but in My Amey and Me, Sewell’s tone becomes raw, the familiarity replaced with stern confession. “Parents have a responsibility to look after their children, I don’t think it’s the same as being friends,” she says. “There were 25 years of me ultimately feeling like I didn’t have a mum, and that was really difficult and confusing.”

“We touched on this idea of intergenerational trauma, and how these colonial histories impact families,” Sewell says. A specialist in transgenerational therapeutics, who features as a guest, explores the links between mental health and the legacies of slavery for peoples of African origin. The suggestion that “illness resides in the family unit” resonates with Sewell’s own view that it is in intergenerational and interpersonal synapses where emotion resides. The episode ends with a moment of mutual understanding between mother and daughter, though one from which the trauma of mental illness and colonialism cannot be extricated.

“We need more of this sense of Britain not just being within the parameters of the boundaries of this island,” Sewell reflects, “but the way that culture has flown out of this place and the echoes come back.” Belonging becomes a perpetually unresolved act in her work, a process in which the personal, social and political require constant balancing within a changing world.

Sewell hopes to evolve My Albion into a writing project. “How am I going to translate this audio into a piece of writing?” she wonders. It is a query that goes to the heart of her fascination with sounds and physical artefacts. Each form carries meaning and memory in different ways. As an archivist, DJ and host, Sewell’s role is to create harmony from the fragments, not just for her listeners, but for herself too.