Like art, food facilitates connection. In Sharing Plates, a new column for Elephant magazine, Ella Slater sits down for an evening spent at the favourite restaurants of contemporary cultural protagonists for an IRL experience.

Before I meet Zeinab Saleh, she emails me asking if I have any food allergies. It’s a good question, but one that sticks with me since a) our venue has been decided already, and b) I probably should have gotten to it first. After all, I am the one taking her out for dinner. As I’ll later realise, Saleh’s forthright question is symptomatic of her outward manner– that is, collected and calm. Much like viewing her paintings, conversation with the artist is much more of a considered act than it is one of immediacy.

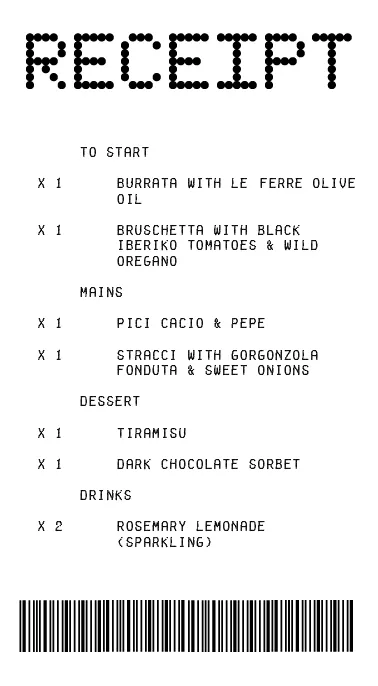

We are meeting as the first iteration of my new column in which artists choose their favourite London dinner destination, and Elephant foots the bill. Saleh’s chosen restaurant is the Shoreditch branch of Padella, the younger sibling of Highbury’s Trullo, and an equally as popular pasta joint. The setting initially seems like an odd choice to me, but the artist explains that it was her lockdown fixation; rather than banana bread, she became obsessed with recreating their renowned pici cacio e pepe, a simple but decadent dish of Tuscan noodles, pecorino cheese and black pepper. We’ve booked for 8 pm– a slightly later table setting to mark Iftar (the breaking of fast), since Saleh is observing the month of Ramadan– and are seated at the bar, overlooking the galley kitchen. I can’t quite make out the details of her dress in the dim lighting, but I notice the Simone Rocha-esque beaded bow earrings she has on since Saleh has a penchant for the designer– I’ve admired the beautiful, intricately ruffled white Rocha dress she wore for the opening of her 2022 Champ Lacombe solo exhibition, ‘j~o~y r~i~d~e’, since she posted photographs of the night on social media.

Our dinner takes place a few days before the artist moves from London– where she has lived for her entire life– to Dubai, a relocation prompted by her husband’s job. It also coincides with her ‘Art Now’ presentation at the Tate Britain, a new series of work continuing the illustrations of domesticity and intimacy, which she has become best known for. In thin acrylics, charcoal, and soft pastels, Saleh depicts homemaking, that most private task, as a refuge for freedoms not necessarily afforded in public, in particular for diasporic communities. Each large canvas is rendered in translucent washes of tranquil blue and dusky pinks; the colours of the sky. Some, such as The Sovereignty of Quiet (2024)– named after Kevin Quashie’s 2012 book on quietness as expressivity, particularly within marginalised communities– feature more easily discernible objects such as prayer mats, open doorways and cats carrying night skies. Most, however, are nebulous and meditative, revealing whispers of decorative patterns and layered colours.

I tell Saleh that a few days prior, another artist friend who had grown up in London had told me that hanging his work in the Tate would be his ‘I made it’ moment. “I couldn’t quite believe it,” Saleh replies regarding her invitation to show with the institution. “It felt like a really big deal– it is a really big deal. My family came to visit, and just to see my mum and younger brothers in this space in my home town was really nice. The Tate is such a grand space; they were like, ‘Zeinab, this whole room is yours?’” I ask if she has ever visited on a public day to eavesdrop. “It’s always interesting to hear what teenagers and school students have to say,” she tells me, smiling over rosemary lemonade. “They’re very unfiltered.”

Predictably, Saleh orders the cacio e pepe, so she barely looks at the menu before choosing. I’m happy when she takes the lead on the starters. As we return our menus, I notice her intricately hennaed hands, which she tells me are for her upcoming Eid al-Fitr celebrations, to be spent with family. Ramadan has been “spiritually cleansing… you become more mindful of what you’re taking in, more conscious of what you’re listening to, what you’re looking at, what you’re eating; you become more in tune with your surroundings”. It strikes me that what she is describing is the same kind of feeling her work provokes: an appreciation for the poetry of the everyday; an adjustment of scale.

Much of Saleh’s early work was derived from her family’s photographic archive, though she does not come from an artistic familial background. In fact, art didn’t occur to her as a career path until she finished school. “When I started my A Levels, I thought I’d become a psychologist,” she says. “I was really obsessed with the TV show Dexter”. Instead, she studied for her BFA at the Slade, where it took until her final year there to switch from the media specialty to painting. In 2018, at around the same time, the university was the setting of various protests sparked by the employment of a racist professor who had hosted a conference on eugenics on campus. It was the latest development in a tangled racist history surrounding the institution. In response to the Slade’s problems surrounding diversity, Saleh, alongside the performance artist Rosa-Johan Uddoh, curated a monumental exhibition and conference titled ‘Widening the Gaze’. The show, held at the Slade Research Centre, aimed to “explore the role of race in creative practice”, and included many celebrated artists such as Alvaro Barrington, Clotilde Jiménez and Ebun Sodipo. “Before we started the conference, which Rosa organised, there were no people of colour teaching permanently at the Slade,” Saleh says, “but now it’s totally different. As a reaction against the university, it definitely had an impact.”

Our main courses arrive. Elephant has asked me to take pictures, which I’m slightly nervous about since the restaurant is dark and crowded. Saleh is much more confident and takes the camera off me determinedly, photographing the backs of the chefs who stood before us. Later on, we’ll be asked to switch the flash off in case someone else on the premises has epilepsy, by a restaurant manager who reassures us, only half-jokingly, that “nobody has died yet”. I’m mortified– I still am, so much so that I have to skip the few minutes in question when listening back to the recordings from our evening– but my companion seems calm and nonplussed.

As we eat, Saleh tells me that, after graduating, she “couldn’t afford to have a studio, so I was working at an arts funding organisation full-time. When I had the opportunity to do my first show, I shared one with a friend. I would be there all weekend, and she would be there on the weekdays.” This first exhibition was CONDO London in 2020, in which the artist showed with Olivia Barrett’s Los Angeles-based gallery Château Shatto, who now represent her. From there, she began showing increasingly, until 2021, when her debut solo exhibition (and institutional show) at Camden Arts Centre enabled her to quit her full-time job. The show, titled ‘Softest place (on earth)’ after a 1998 single by the girl-group Xscape, was my own first encounter with Saleh’s work, and featured a series of richly textured charcoal paintings and drawings in earthy and grey tones: illustrations of the ephemeral nature of intimacy on a monumental scale. It was this show which also caught the Tate’s attention, namely that of Isabella Maidment, their Curator of Contemporary British Art at the time.

We both clear our plates. I am learning that interviewing over dinner is kind of like a dance, requiring equal parts talking and eating from both parties. As we order dessert– tiramisu for Saleh, dark chocolate sorbet for me– I ask the artist about her involvement in Muslim Sisterhood, a creative agency and community platform, also founded during her time at the Slade, alongside Sara Gulamali and Lamisa Khan. She tells me that the group has worked on campaign consultancy centring Muslim women with brands ranging from Nike, Disney, Converse, and recently, Crocs (she has bought her siblings the shoes as Eid presents). The Crocs campaign was cast by Saleh, who also provided consultancy for the project, and was inspired by her recantations of familial excitement and communion during Eid. She sees her work with the Muslim Sisterhood as an antidote to the oft-solitary working life of an artist; a way to “work with other people”. The artist tells me about the public programme she curated alongside her co-founders, to run at Camden Art Centre throughout ‘Softest place (on earth)’: belly dancing classes and self-defence workshops, both prioritising the inclusion of Muslim women.

At this point, it’s late in the evening; the restaurant has almost cleared, and the carbs have made us both sleepy. I have a few final questions, about Saleh’s own personal art collection: she collects art she loves by people she loves, such as a monoprint by Sola Olulode, painting by Okiki Akinfe, and an artist edition of Tunisian olive oil, by the French-Tunisian artist eL Seed. She tells me that her dream acquisition would be a sculpture by the Palestinian installation artist Mona Hatoum, or a painting by Kerry James Marshall. She also likes to collect souvenirs from exhibitions: “I have a little piece of cracked paint that was on the floor of Anselm Keifer’s retrospective at the Royal Academy in 2014, and a Yoko Ono sky puzzle piece from the Tate 2024 show.” Then it’s time to hug and part ways– as well as, in Saleh’s case, to go home and pack. Plus, work doesn’t cease for the artist– she is returning to London in November for another solo exhibition. It’s enough to make anyone stressed, but I get the impression that she’ll handle every bit of it with that which exudes from her work: a sense of calm resolve.

Written by Ella Slater