There’s something about the light in St Ives, the way it filters through the streets and glints off the sea. Turner delighted in its woozy effects in the early 19th century, and after the opening of the Great Western Railway in 1877 more artists sought to capture it in paint. From the 1940s to the 1960s, this unassuming fishing port on the Cornish coast became a centre for modern British artists, who produced abstracted views of its boat-filled harbour and the local landscape. But it turns out that another, more spiritual, kind of light was also guiding their work.

“After the Second World War, Western artists found comfort and inspiration in Eastern spirituality and philosophy,” says Calvin Hui, co-founder of 3812 Gallery, hosts the exhibition Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism

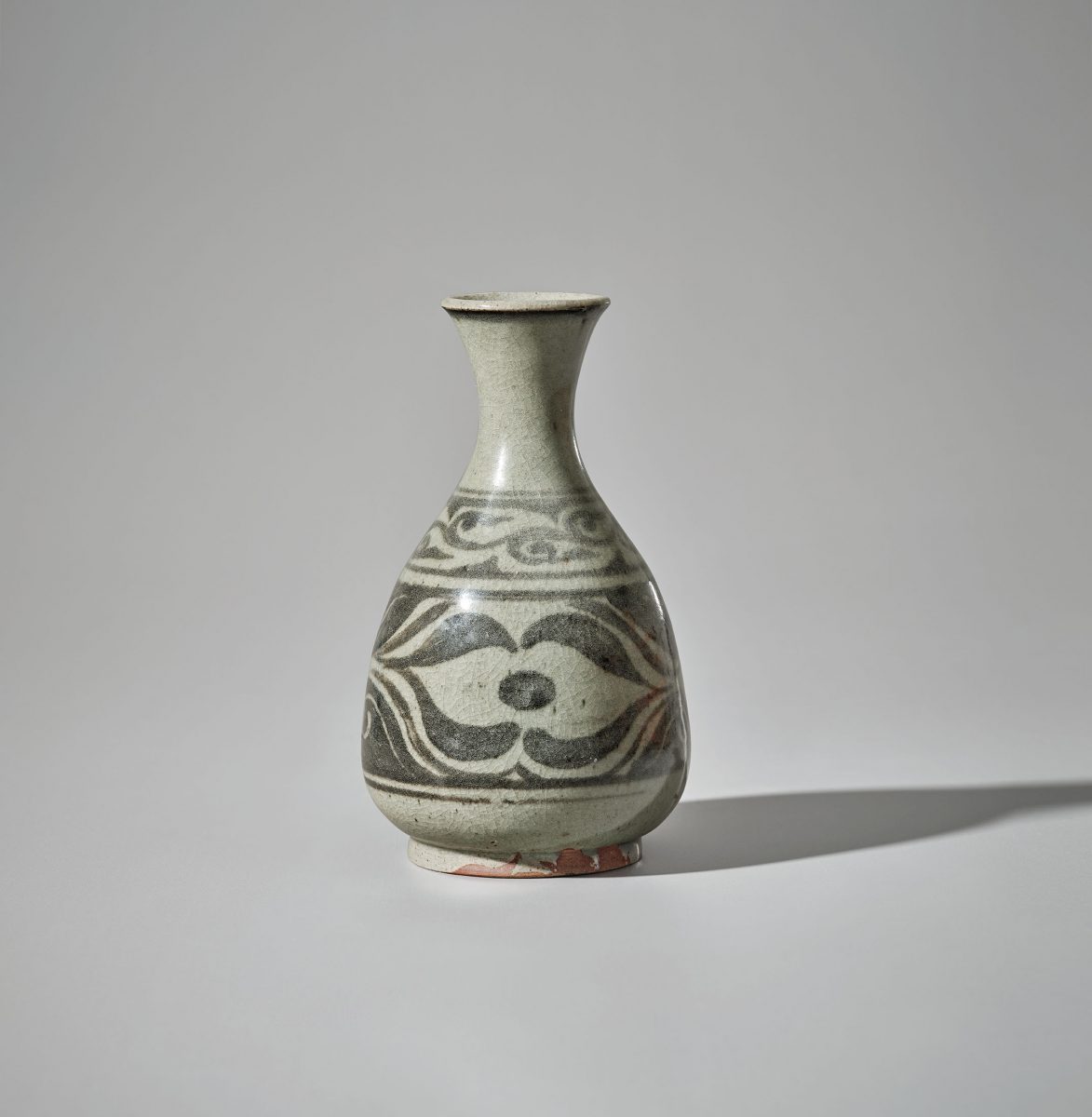

. In fact, Buddhist ideas of art and culture were introduced to the area in 1920, when Bernard Leach and Shōji Hamada travelled from Japan to St Ives and established the progressive Leach Pottery studio. Leach, who was born in Hong Kong and trained in Japan, saw himself as an interpreter of the Japanese ceramic tradition, and a bridge between East and West.

Timing is everything and in the wake of the Second World War individuals and ideas began to cross countries and continents more freely. Texts such as Zen in the Art of Archery (1948 in German, 1953 in English) by Eugen Herrigel, a German philosopher previously based in Japan, found international readers, among them the St Ives artist Bryan Wynter.

“It was almost inevitable that Wynter should find and be compelled by Zen in the Art of Archery,” writes Philip Dodd in the exhibition catalogue. “After all, in the 1940s he had written a dream diary and undergone Jungian analysis. What might initially seem more surprising is that Wynter then went on to experiment with drugs, or rather mescaline. But if one zooms out from St Ives and looks at the wider cultural world, what Wynter did was not at all unusual, to explore Buddhist and psychedelic routes to spirituality.”

“Timing is everything and in the wake of the Second World War individuals and ideas began to cross countries and continents more freely”

The foreword to Herrigel’s text was written by the Buddhist scholar Daisetz T Suzuki, whose teachings heavily influenced Leach’s designs, which often adhere to the Buddhist principle of harmony. In 1955, Leach invited Suzuki to stop off in St Ives on his way from Japan to California, and he spoke at the Leach Pottery studio to a small audience that included artists Trevor Bell, Barbara Hepworth and Brian Wall. In 2012, during an interview for a film about his work, Bell said, “[Suzuki] seemed to be saying everything that had to be said about what I was feeling, feeling that I had to do. That concern has been with me all my life, it’s affected the way I’ve worked.”

The St Ives School, as the artists associated with this stretch of the Cornish coast are now known, came into its own during this period. In the 1950s, a clutch of younger artists gathered in the town together with Hepworth and her then-husband Ben Nicholson, who had settled there at the outbreak of the war in 1939. “They were young, dynamic, avant-garde: they wanted to explore new things and build a better world in their art,” says Hui.

“Suzuki seemed to be saying everything that had to be said about what I was feeling. That concern has affected the way I’ve worked”

When Buddhism arrived in the remote town, it was exciting, exotic even, and after the dark days of war it gave new light. A deep affinity developed between Buddhist philosophy (with its spontaneity and its freedom of expression) and these painters and sculptors who through colour and form were giving a new lease of life to the landscape.

Although Buddhism manifested itself more in their work in a spiritual rather than a physical fashion, Hui notes that there are visual cues on the canvases of the St Ives artists that point to an Eastern disposition. In the 1950s and 1960s, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (who had left her Scottish hometown of St Andrews for St Ives a decade earlier) became drawn to circles, which in Zen Buddhism symbolise continuity, perfection, the circle of life. Cornish painter Terry Frost turned to the motif of the circle, too, and in keeping with the Buddhist mantra of “less is more” restricted his colour palette. Buddhist monasteries and shrines became a point of reference in the work of Bell, whose abstract drawings and paintings were also increasingly pared back.

“They were young, dynamic, avant-garde: they wanted to explore new things and build a better world in their art”

The London outpost of 3812 Gallery, which was founded in Hong Kong in 2011, opened in November 2018. That summer, Hui had spent a weekend in St Ives and encountered the vivid creations of this generation of artists. Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism tours to London from Hong Kong, and Hui’s plan is to produce an annual exhibition of British modern art that bridges both spaces.

“We want to explore the cultural connections between East and West in art, and to provide a new perspective on this movement,” he says. “Today, we’re so close, and the influence is clear in contemporary art. This is about showing that globalisation started earlier. It’s about building a cultural dialogue.’

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, was published in April 2022

Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism is at 3812 Gallery London from 13 July to 3 September 2022