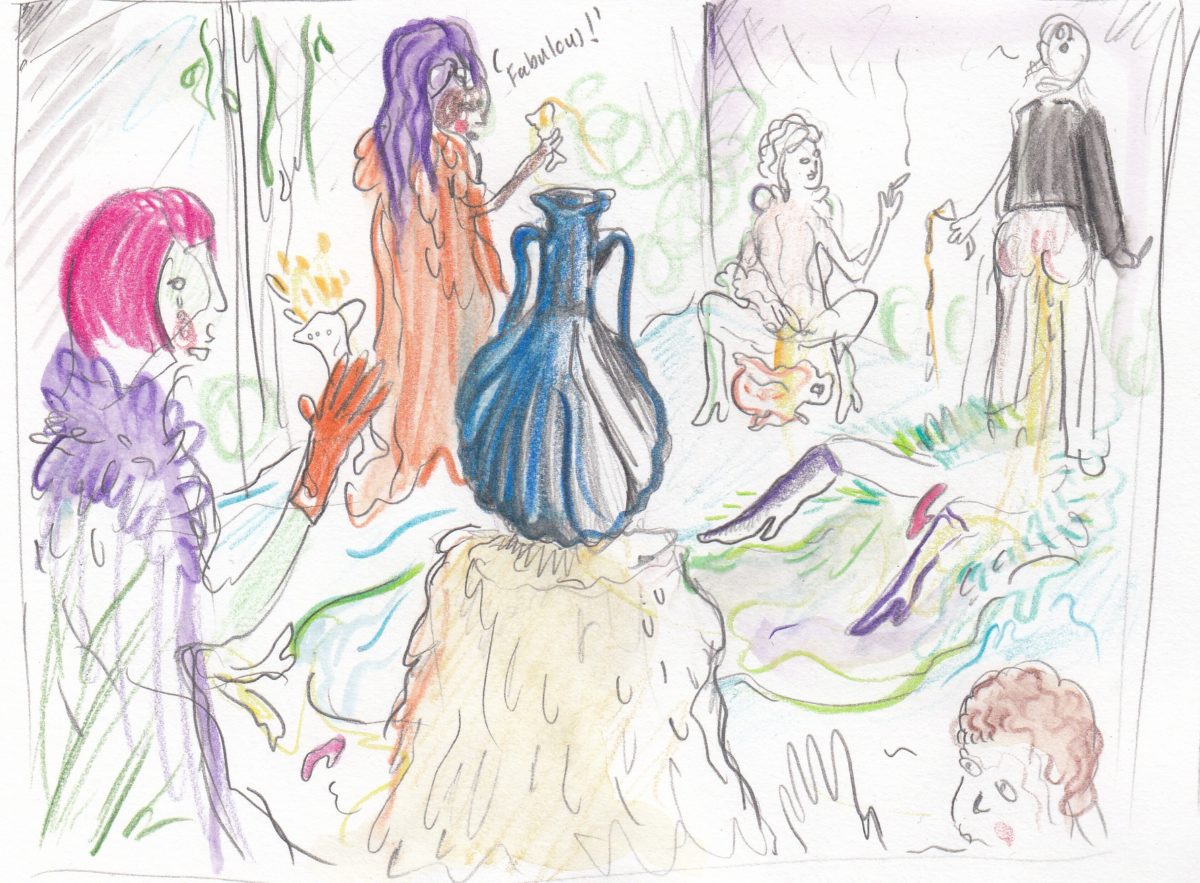

Ceremony of the Void, 2017, installation and performance in DRAF Studio. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Antoine Levi, Paris. Photo by Dan Weill

What happens when you combine cake, ceramics and lots of colour? British artist Zoe Williams has made a name for herself with her joyously exuberant work, spanning performance, video, sculpture and drawings. Here, you’re as likely to find over-the-top wedding cakes as you are a magical perfume bottle with the power to unlock your darkest fantasies—as is the case in her brand new installation and film.

Just unveiled at new London gallery on the block, Mimosa House, which focuses on representing female and queer artists, her exhibition (titled Sunday Fantasy) explores the imaginative potential of desire. The film, created in collaboration with photographer and filmmaker Amy Gwatkin, unpicks the power structures and representations of the erotic to question what really feeds our fantasies.

You often use ceramics in your work, making full use of its very tactile and sometimes even lumpy potential. How did you get into ceramics, and what appeals to you about it?

I’ve been using ceramics on and off since my degree, which I finished in 2006. I’ve always been really attracted to it as a material. It’s somewhere between craft and functionality, and it hasn’t been traditionally related to being a fine art process. It can be very sensuous—it can mimic the body—and the way that you make it is very physical and performative. It’s quite organic. I find that really seductive. It’s a therapeutic process too, and can be quite grotesque.

I started to make ceramic shoes partly because I’d been really obsessed with Carol Rama’s shoes. I wanted to extend people’s bodies into shoes. My latest show is about creating an imaginative, childlike world. There’s an immediacy about it. Shoes are a desirable object that I really wanted to make, but making them in clay renders it sort of redundant, and a bit wonky.

“Colour is good for playing with excess, and I want things to be mesmerizing but also a bit too much”

Your work is very attuned to colour and striking colour combinations, in pastels and bright contrasting shades. How important is colour for you, and where do you draw inspiration for this from?

It’s really important for me. I like the idea of a seductive palette, some that are more soft on the eye and then others that pop out or disagree with that. Colour is good for playing with excess too, and I want things to be mesmerizing but also a bit too much. Colour can be quite hallucinogenic.

My practice started in painting and drawing, and that’s always a foundation for me. I always seem really drawn to older paintings, Cranach for example, and almost a sacred use of colour. Also, colour can have some quite heavy associations, and there’s something about gendering it and then messing around with it. People can dismiss colour for being decorative rather than having a critical angle, and it can be dismissed as frivolous. I want to challenge that.

Food has come up several times in your work. What role does it play?

The tension between seduction and repulsion attracts me. Also, food is a medium that’s not traditionally an art material, although it has been used and referenced a lot as a symbolic material. There’s the ritualistic aspect with things like dining, and I find it interesting how food has been represented in different cultures. For me, it’s very good at representing a kind of excess, and there are a lot of taboos around food, where you become disgusted by things early on.

I have been using cake in performances and my work in general as a material that is associated with decoration and celebration, but that can easily be tipped into something that becomes more grotesque. It starts off very fairytale and baroque-wedding, and then it becomes abject and quite confrontational. I’ve done performances where it goes towards horror and gore, and then there’s the ethics of waste too. The last performance I did I had some quite visceral reactions. It was in Monte Carlo, and some people thought that this banquet of excess was about them.

- Left and right: Sunday Fantasy, 2019, film still, co-directed by Amy Gwatkin, courtesy of the artist and Antoine Levi gallery, Paris. Commissioned by Mimosa House and supported by Arts Council England

In your new show at Mimosa House, you are presenting a film that explores the language of fantasy and the erotic. What does this mean for you?

Fantasy is not necessarily politically correct, but it’s giving you freedom to dream about something. It allows your imagination an access-point to a subconscious idea. How do you represent that in film? It could be seen as quite frivolous but I think there’s something quite important to look at how desire functions. It’s not about straightforward depictions of sexual gratification, but rather this other, more complicated way of dealing with fantasies that could be about many things.

The film has aspects of B-movie, and it’s quite silly in places, and then there are much more vulnerable aspects. I’ve wanted to make this work for a quite a while. I felt it was important to use fantasy as a transformative tool.

“Fantasy is not necessarily politically correct, but it’s giving you freedom to dream about something”

You’ve collaborated with a number of other artists, filmmakers and set designers. How do collaborations like these feed into and define your practice?

It’s really important to me that the work doesn’t just exist within the art world, and that there are these other disciplines that it can feed into. I want it to be functional in another realm. It’s that idea of not being too precious, and trying to mess a bit with that hierarchy. Working with people who aren’t all visual artists, it just brings other voices in, and we all have different roles. In terms of ownership, I don’t really like the idea of one dominant artist or author, and I think it’s good to play with and allow other voices to be heard.