The combination of artists based purely on their femaleness can at times feel gimmicky. Here, it feels fun and celebratory, drawing on far more intricate common threads than gender alone.

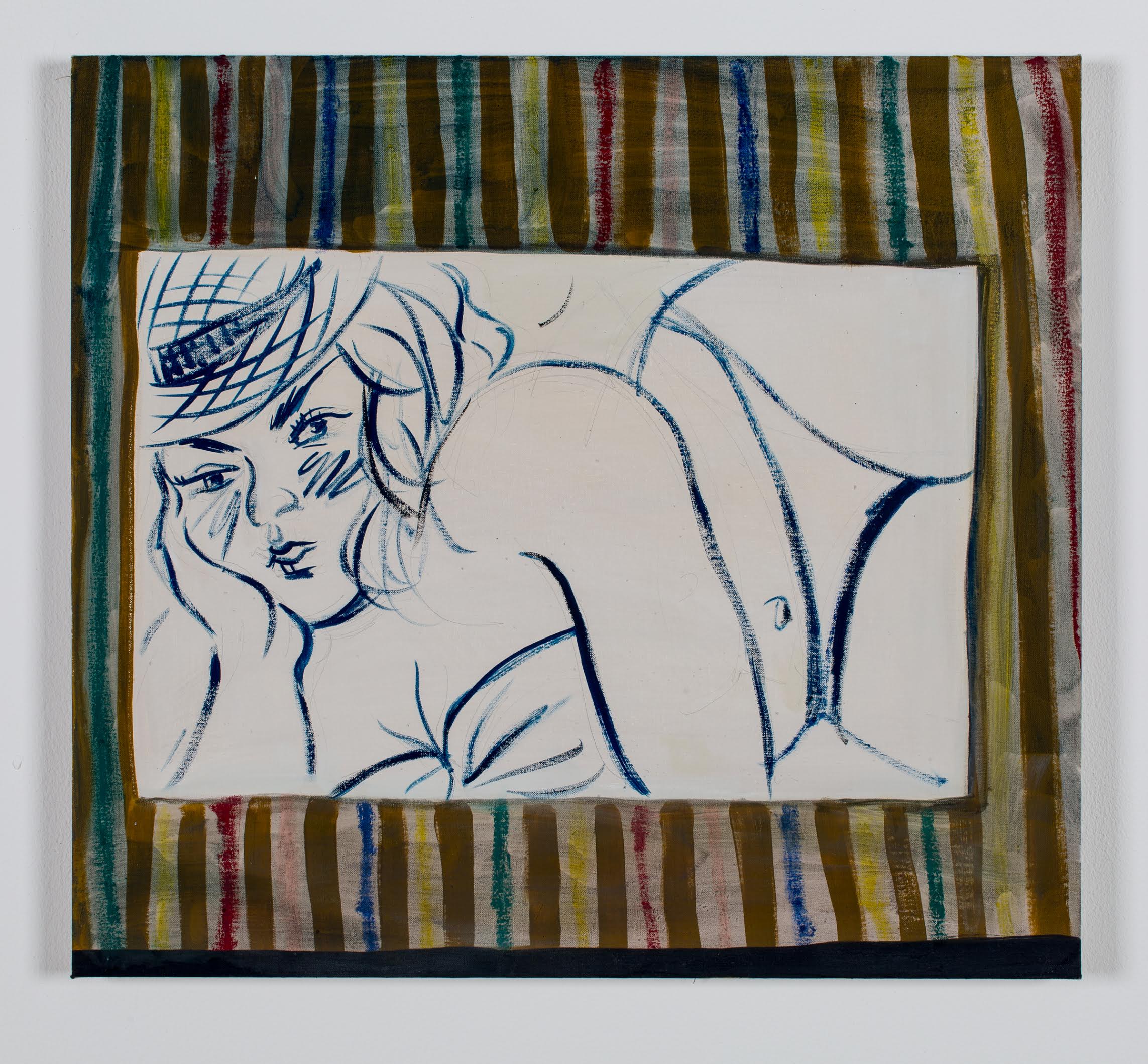

A giant yellow sunshine from Laura Aldridge (Be a Nose! #2, 2014) greets visitors as they enter the clean, white space, grinning down from a big blue disk which is hung from the ceiling. To the right of this, Cornelia Baltes’s Twiste wo ich swinge I shows under-panted skinny buttocks (presumably male, but perhaps not, viewers spent a while pondering this on opening night) jiggling against a sunflower yellow background—one of the few outright depictions of the body in the show.

There are two key modes of thought here: the first looking at artistic positions which explore psychological, erotic and instinctual elements; the second at abstract mark making and production. This springs from the exhibition’s starting point around 1940, when both Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism coexisted in New York. The influence of these two movements can be seen in moments throughout the show, but the work moves in many directions beyond this (it is important to consider the heavily male weighting that these movements have been imbued by history, however).

In the lead up to the exhibition, it seemed unimaginable to picture so many artists fitting into this space without seeming too noisy, but the floor has been used economically, with only a few works to navigate away from the walls, and the many wall-hung works are kept within relatively tight sections with plenty of white space around them.

Painting is a key focus here, and some of the non-wall-hung works have painterly aspects to them also, especially Aimee Parrott’s deep aubergine Pelt (2017) which droops rug-like in the middle of the room, the nude body hung upside down in the manner of a drying animal skin.

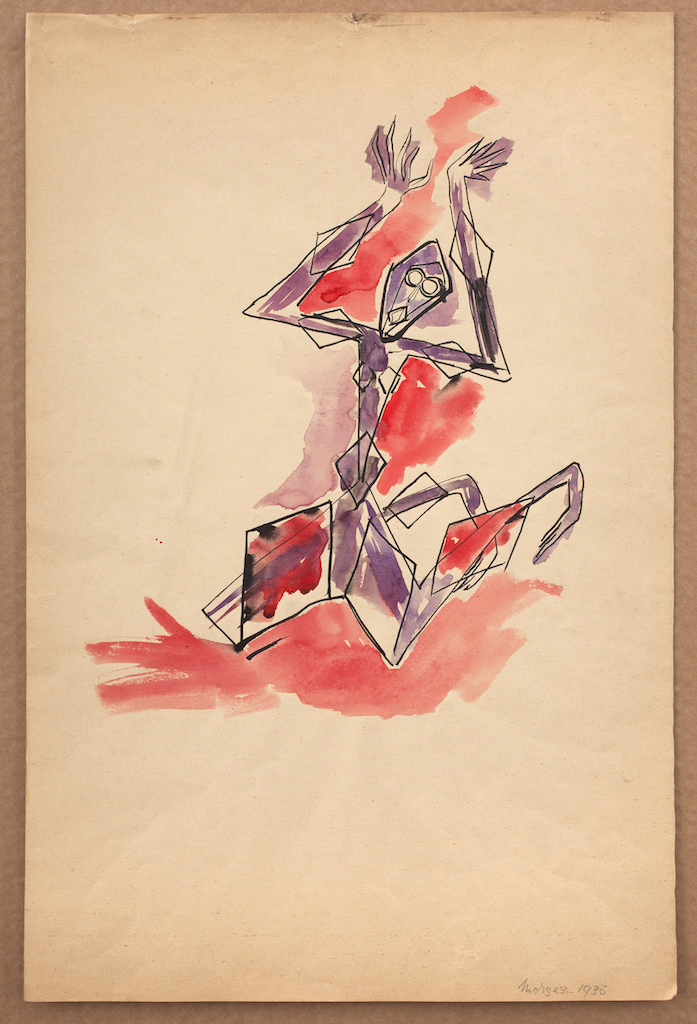

One small section of wall holds thirteen works, nestled together in close proximity. Clare Woods’s Babs the Impossible (2014) is a lusciously painted highlight in the middle, a single foot depicted in deep pinks, dusty blues and browns. It plays well with the Catherine Yarrow’s neighbouring Kneeling Purple Figure (Morges) from 1935 which is both soft and hard—watery red and purple tones depicting an angular figure which looks as though it is screaming in despair or possibly on fire.

Clare Woods, Babs the Impossible, 2015, Oil on aluminium, 70 x 45cm, Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, Breese Little

The perpendicular wall holds some of the most exciting artists of the last few generations, with well-established names such as Bridget Riley, Rachel Whiteread and Tracey Emin alongside newer and no less brilliant artists such as Ella Kruglyanskaya. Whiteread’s Step is particularly enjoyable, a simple plaster and resin work that again holds both hardness and softness—the bottom plaster bricks looking as though they have come directly from a building site, the upper pink and orange resin bricks looking jelly-like and rather tempting to take a bite out of.

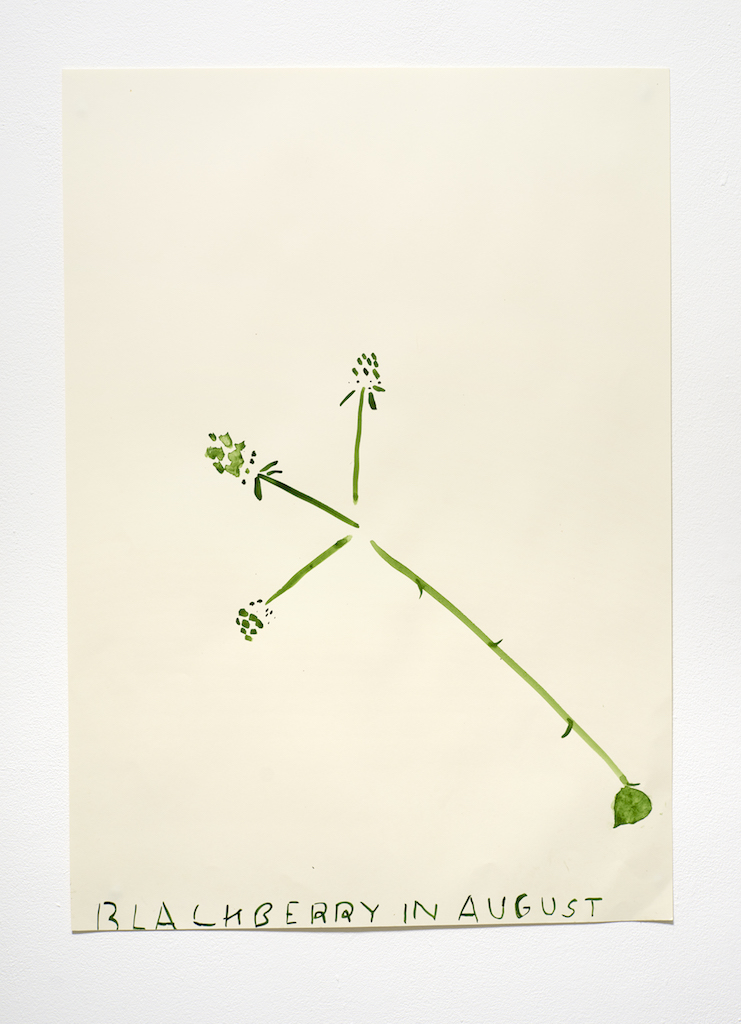

It’s good to see such a mix of career levels here—this isn’t about presenting the female artist as a new or changed phenomenon, but a constant force. Some are just getting started, others, such as Rose Wylie, have been working for years and are just getting the recognition they deserve (a discovery later in life which is being reflected frequently at the moment, not least in the career of Phyllida Barlow and her current representation of Britain at the Venice Biennale), and others have been part of the art world fabric for a long while. A celebration of female artists but also of art in general, at its most spirited.

- Rose Wylie, Blackberry (Minimal), 2015, Watercolour on paper, 84 x 60 cm, Courtesy Union Gallery, Breese Little

- Catherine Yarrow, Kneeling Purple Figure (Morges), 1935, Pen and watercolour on paper, 43.8 x 28.9 cm, Courtesy Austin Desmond, London, Breese Little

’31 Women’ shows until 31 July at Breese Little gallery in London. breeselittle.com