What can we expect from your upcoming exhibition at von Bartha?

A well-organized mess! I decided to ignore the vast rooms in the gallery and instead create a straight path running from the main entrance all the way to the back of the gallery, stretching through the entire space. All the works in the exhibition are emerging from this slice, like sparks of life bursting out from a single DNA string.

How will the idea of the membrane be addressed in this show?

Many of the works have a two-dimensional physical structure, opening up to a third and fourth dimension once you start exploring them. Pieces of paper become ancient or future landscapes and the note board in the video becomes a gateway to unseen scenarios. When I used the term membrane to explain some of my works I was referring to something organic, a surface that is evolving differently depending on its surroundings, and that is the way I relate to the structures I take use of. Out of these membranes I make collages, where different times, stories and facts are openly patched together. In the exhibition at von Bartha these collages map a situation of change, where some pieces illustrate an overview of this shift and others expose new structures being formed. In any case the works together form a carbon copy paper, attempting to trace that very moment where one state of mind is changing into another one.

What is it about natural history and museum displays that excites you? And do you remember a starting point for this interest?

When I arrive in a place where I haven’t been before I often try to make time for a visit to the natural history museum in that specific town or city. The way nature is organised and labeled in those museums often tells you a lot about how that geographic area looks at nature and its history. Depending on where in the world you are, what objects and theories are highlighted differs quite a lot. This semi-transparent power has always fascinated me and one could claim that this attitude can be found in museum collections generally. The futile attempt to use a limited collection to explain ‘history’, ‘art’ or ‘nature’ of course creates blind spots, stories or events sorted out. These missing links, existing but invisible, have always fascinated me. You could say that my interest in museum displays is about what isn’t there, what was left out.

When I was a kid, living in Stockholm, I visited the museum of natural history there a lot. Some might say too much. I had my own favorite place, a big hall where whale skeletons were hanging from the ceiling. These enormous, floating bone structures never ceased to amaze me. In the middle of this hall was a small booth, completely dark, where you could listen to the recorded sounds of different whales. I sat there in the dark, imagining that the sounds came from the hovering skeletons in the hall. It’s still one of the most impressive sensations I ever had in a museum, and from then on I’m sure I was hooked.

You’ve previously mentioned that you wanted to begin working with film as it would add ‘a clear notion of fiction’ to your work. Now that your films have shown, and been seen, in various places, do you feel this has added the dimension that you were looking for?

If anything, I realised that many of my works actually are a work of fiction, or at least some kind of hyper-fiction. Perhaps it took the production and reception of Dreamcatcher to make that clear to me. I also became aware of the fact that I treated the video very much like a sculpture, or even more as a method of tracing the physical elements found in the video. I set out to make a metaphysical statement, but seen from one point of view the video is very concrete: the film is basically about a pin board in a room being scrutinised to absurdity, and from this scanning the surface comes to life and starts dominating the whole structure of the film. It’s really like a crash-test film, testing the limits of certain documents, spaces and creatures by forcing them together in one single document.

How do you begin planning a work like Dreamcatcher? Are you quite loose with your approach, or are you very set in what you’d like to create?

In 2011 I made a big installation called From Lucy With Love, based on a variety of stories and objects on display in a big vitrine. That work became a set of footnotes for my obsessions and inspirations during the years leading up to that point. In many ways the Dreamcatcher document is a Lucy 2.0, using the same source code to further investigate certain areas I like to dwell in. The difference is that Dreamcatcher

carries a quite cannibalistic tendency. While the stories in Lucy were safely organized behind glass, with the different parts claiming their own territory, Dreamcatcher is gradually dissolving the barriers, or membranes if you like, between the different parts. This finally leads up to a collapse of the very structure of the narrative, with a new story being born because of the end. It’s not an ending, but a break.

To answer your question: the idea for Dreamcatcher started and developed in a very organic manner. The piece is filled with ideas and images that have been with me for years and now I decided to make a map out of them. The big difference compared to earlier works was that I deliberately invited other minds to shape specific parts of this map, with animations, editing, sound design, etc. This was a way for me to actually lose control over this configuration, to heighten the feeling of all these different ideas and events being autonomous, bound together only by this map. I told someone that I designed the piece to try to have a clearer meaning in the future, to carry some future sense, and it’s still true. Dreamcatcher is a sketch, designed to fully unfold in a future when ideas and events have caught up with it. Of course I can’t be sure that this will ever occur, but that is nevertheless what it’s designed for. The point for me here is to use imagery to convey the feeling of a deeper future insight yet to be experienced. This is tricky, partly because it also involves myself, since I don’t fully understand this either. I simply share my confusion with the viewer, proposing a couple of guidelines that one day might lead to a wider understanding of this visual entity, and the material it is entwined with.

‘Christian Andersson’ is at von Bartha, Basel from 15 June to 23 July 2016

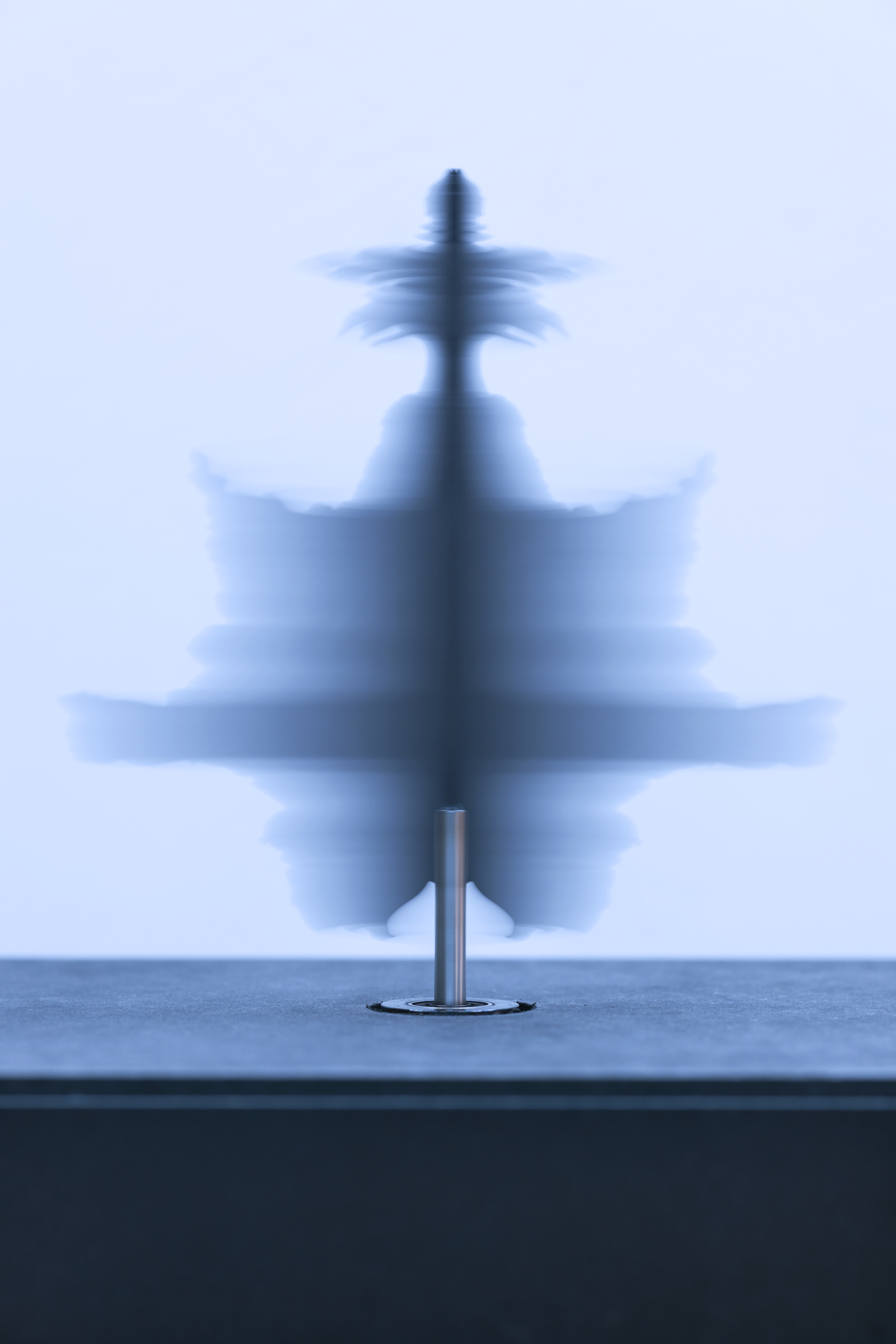

Christian Andersson, Self Portrait / Living Fossil, 2013, Framed C-print, (69,5 x 96,5 cm), courtesy of the artist, von Bartha Basel, Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art, Lisbon, Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm