Can you tell me a little about the body of work, Lausanne, which you recently showed at Ellis King gallery?

Lausanne assembled sculptures and paintings that attempted (and succeeded to a large extent) to design an art exhibition. I was trying to satisfy my idea of what makes an exhibition good, interesting, cool, meaningful, and what it looks like. I had an instinctual desire to understand; it was an almost uncontrollable desire that became crucial in the process, more than a fresh set of works of art ready to be shown, more than bringing the art out of the studio and into the world.

The first section of the accompanying text reads like a love letter (albeit, perhaps a less than simple love!) to your current hometown, Lausanne. What was it about the place that interested you and how has it influenced the direction of the work?

The title appeared to have more heft than others I had in mind. Lausanne is the fascinating city where I live, it was more elegant than logical to use this title. The text came after. The enigmatic late 19th-century painter Félix Vallotton, born in Lausanne, in a letter to a friend describes Lausanne as a place that invites indolence and contemplation more than action.

Your pieces—similarly to your written texts—swing between poetic and practical in feel. The sculptures and paintings sometimes reference known items and objects and at other times veer into abstraction. Are you interested in the tension and apparently opposite nature of these elements or do you hope to convey a sense of clarity, breaking down fixed ideas of how we imagine things should be categorised?

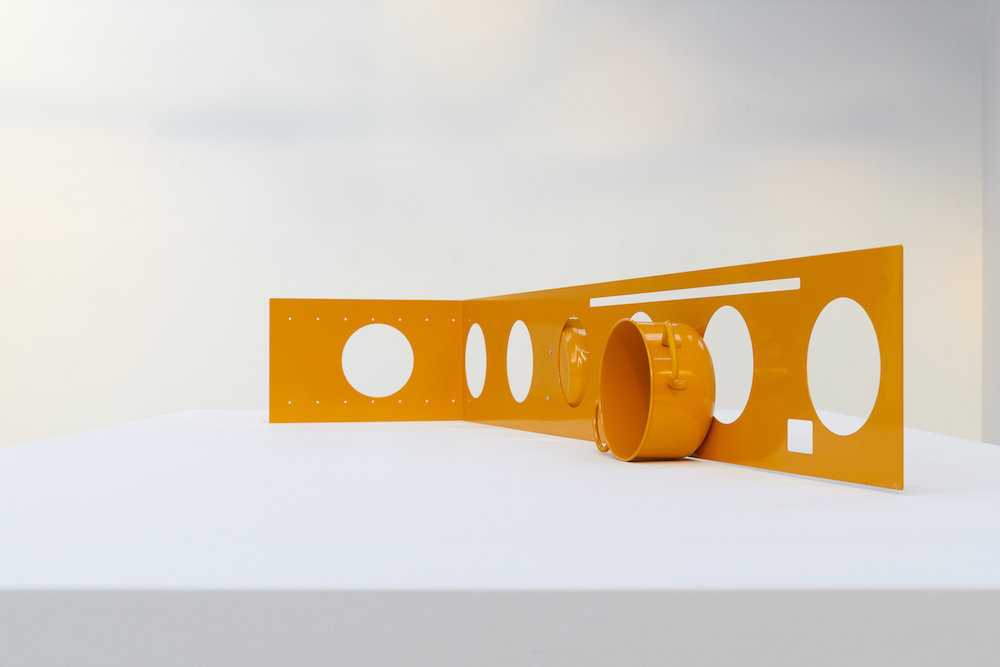

The show granted a kind of equivalence, each piece is made to seem more or less equal… equally important. Paintings are props, boxes are positioned to fill the space and to “balance voids”. The show was specially designed to be clear. I wanted a normal, established look.

It’s previously been mentioned that you create self-issued obstacles in your practice. What might these be and do you aim to overcome them in the work?

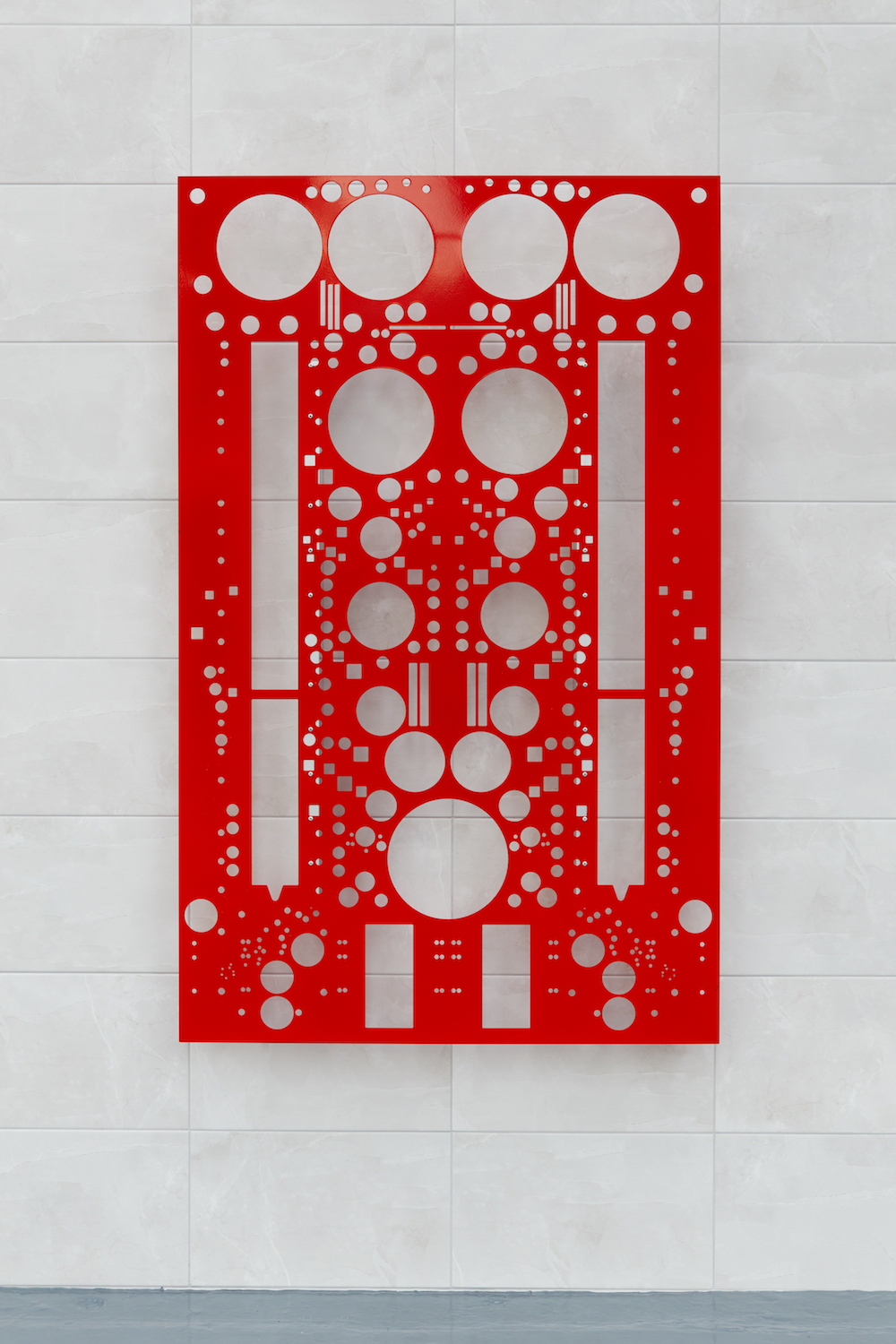

I definitely created self-issued obstacles, delegating the production of most objects in the exhibition to other people. My intervention comes only at the moment of installation. I had a show in mind that could contain a single artwork–again, a perforated metal plate–which is why I was not worried about being in control of the rest, this in itself could be an obstacle. I leave a large margin of indeterminacy to the fate of the exhibition, but not as an attempt at conceptualism, it’s more about my attitude. I could have exhibited a minimal set of plates all around the gallery, but that would have been a celebration of art. Although in some ways I did the expected; using art clichés as a mural, a soft sculpture, an appropriation, a chair, bad paintings and so on. I hardly accept these objects as my own, but they help me flatten the setting and create a useful scenography for a non-hierarchical show. It’s about rejection of authorship. In this show in Dublin, there was a certain hidden irony that represents both respect and disenchantment for art.

Your studies were in New Technologies for Art, before taking a Visual Arts MA. How do you think that eventually influenced your work?

It definitely influenced me. The name New Technologies for Art in Milan stands for “no facilities”. The university shares the classrooms with a decadent high school in the suburbs. I never produced a single artwork in the three years of my bachelor. It was great.

ellisking.net. Emanuele Marcuccio is part of a group show at Carl Kostyal in London in July.