Can you tell me a bit about the work that will be shown in The ends that matter at Delfina Foundation?

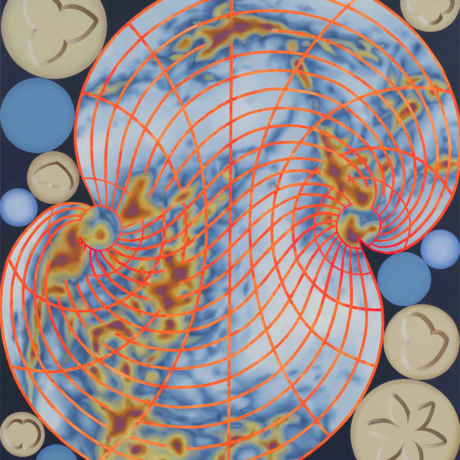

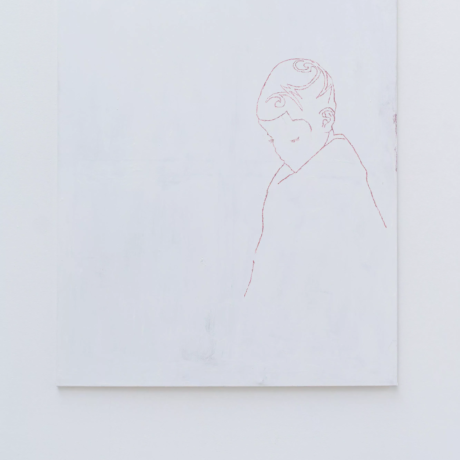

The exhibition is primarily focused around a three-channel video that ‘translates’ my experience as an observer in the City of London Magistrates’ court in central London. Related to this work are a screen-printed textile work that mimics the curtains that covered the wall in the courtroom, a metal text work installed in Delfina Foundation’s gallery courtyard, and some drawings.

How did you find your experience in court?

Court was a very contradictory experience. At one and the same time I recognized that the functionaries of the court – the magistrates, clerks, solicitors and barristers – were working with deeply held compassionate belief in the principles of open justice and that these legal systems – in the UK and Canada and elsewhere – are mired in institutional racism, classicism, misogyny, and non-gender conforming bias.

How contrived were your own recordings of the courtroom — whether in memory, writing etc. Did you have a strict process for capturing your surroundings or has this been very organic?

Firstly, I love the word ‘contrived’; and yes, my ‘recordings’, that is, my notes, were highly contrived. My process for taking notes, to remind myself later of the exact events, was to write pointed connections to things that other things reminded me of; for instance, when describing the courtroom finishes and fixtures I would make associations with textures, colours and shapes that were within things in my own house or that I saw regularly; when describing barristers, magistrates, defendants, or witnesses, I would write about them by recalling television or film stars or friends or acquaintances. It was a completely subjective process and that personal bias is, in the end, the thing that has shaped the work. Rather than ameliorate the sense that the work is contrived, this artifice is a structural and formal component of the work.

There’s a question around the ‘gap’ between documentation and experience raised in this exhibition, surrounding photographs, videos, documentary sound and so on. Do you feel these mediums all offer a different view of reality? Or are they all part of a wider mass that builds a collective world, or sense of understanding aside from direct experience?

Your use of the word ‘gap’ here is essential. Slavoj Zizek speaks of the essential ‘parallax error’ or ‘gap’ between a material, as such, and the experience of that material in the world that forms subjectivity; this is fundamental to my thinking of documentary and its function as an abstract medium – that is, as a medium that is reductive, fragmentary, compressed or condensed in its structural assemblage, its editing, as in so, a medium that can open up possibilities of sort of radicalized sublime. I attempt an inquiry into this in the videos as my out-of-focus hand caresses crisp appropriated photographic images taken from online image streams of photojournalism and personal feeds on Tumblr. This narrative structure of the image stream or news feed is central to the project: I am recounting my ‘sensed’ experience in court through photographs that I have selected based on the ‘sense’ that I was reading onto and feeling from other people’s images–telling my experience through the subjectivity of another’s online image curation. Whether it’s someone’s Tumblr page of images of sexy bodies or a photo-editor’s ‘objective’ selection and cropping of an image of conflict, I am interested in the confrontation and translation of their decisions with my own biases as form for the work. I mean, this is the reality within which we make and understand representations; the restrictions of making representations in court is completely antithetical to this and so, becomes furtive ground to step outside and analyze.

Do you feel conversations around the truth, or reality, of the filmed image have changed drastically since you began working?

The stakes around ideas of ‘truth’ in representation are so different for everyone: there are many artists turning to a more esoteric, seductive, and less ‘academically’ conceptual form of practice, and while that may be highly compelling to me, I also know that it is a privileged position to take because, for many of us, conversations about ‘truth’ remain essential to confronting the real violence of the world.

‘That ends that matter: an installation by Jean-Paul Kelly’ is open until 12 November 2016 at Delfina Foundation. All images: Jean-Paul Kelly, installation view of ‘That ends that matter’ at Delfina Foundation (2016). Photo Tim Bowditch, courtesy Delfina Foundation