Can you tell me a bit about Ophiux?

The ideas for Ophiux started out on a residency at Wysing Arts Centre in the spring of 2015 for their programme titled The Multiverse. Rather than thinking about the multiverse as something outside of our own worldview, something that lies beyond, in outer-space or elsewhere, I wanted to focus our own environment. Much of the world’s natural life remains undiscovered, for all our technologies we still don’t know most of the bacterial life that exists on the palm of our own hand. We frequently hear about scientific discoveries that dispel our preconceptions; life-forms that have evolved to deal with intense conditions and hostile environments. One of the most perplexing is the existence of complex communities of creatures in deep volcanic ocean trenches that survive in extreme heat without light or oxygen. To us they are inhabitable ‘alien universes’ and have the potential to change our preconceptions and theories. They are not part of speculation or science fiction and indeed are much stranger — these ‘alternate universes’ exist here on earth.

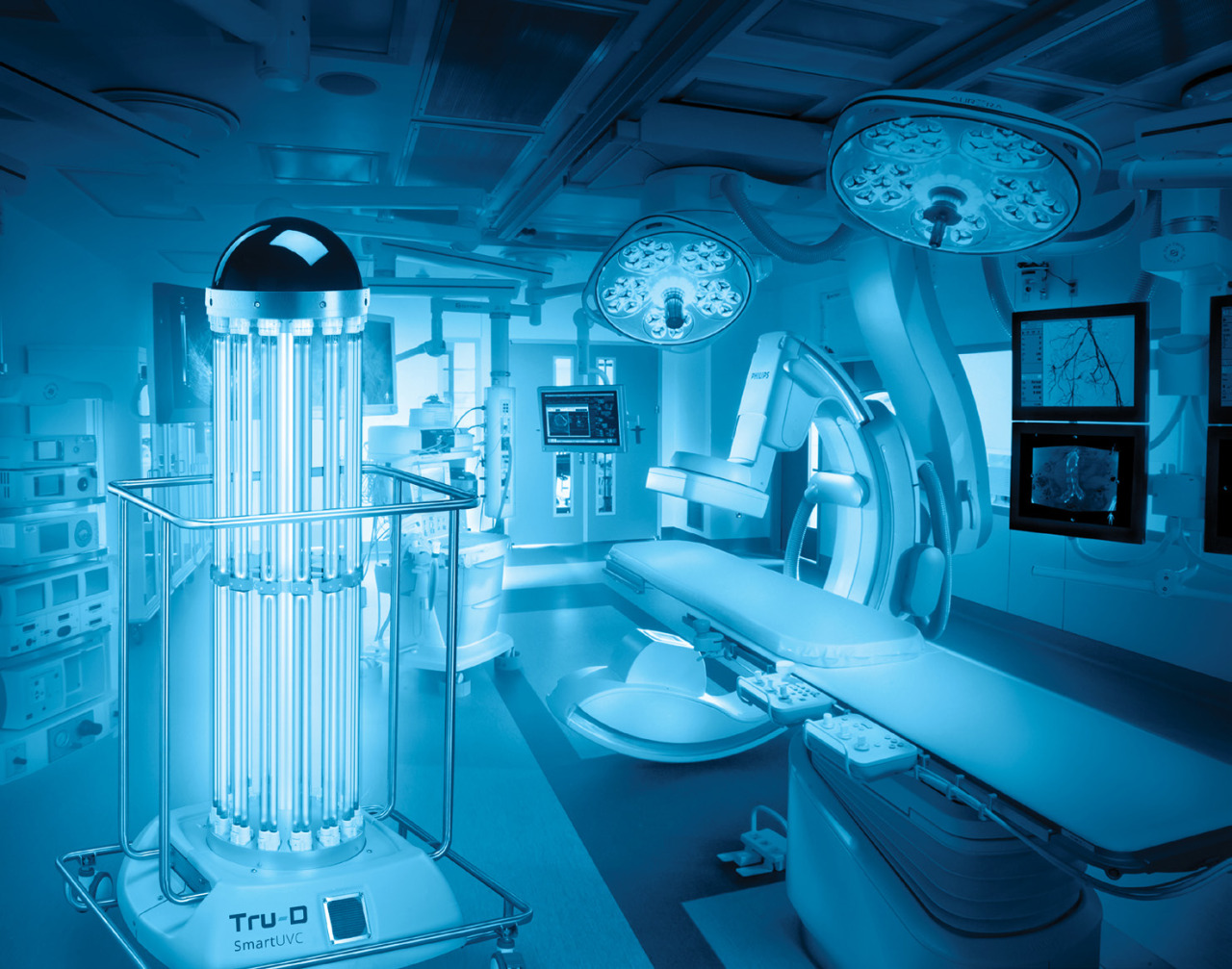

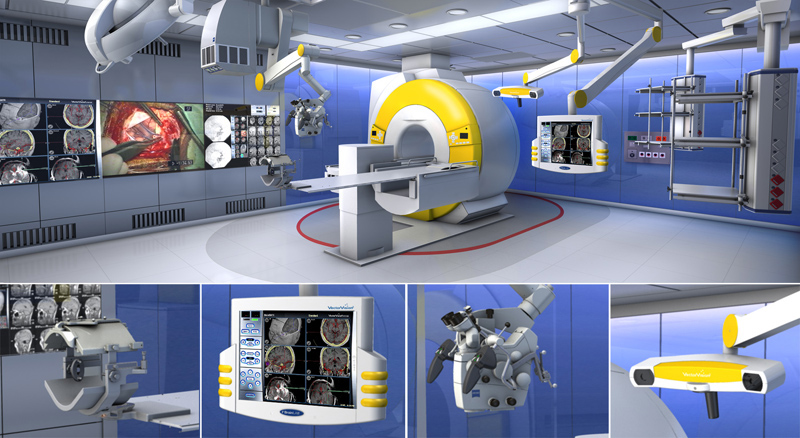

On the residency I was introduced to two scientists working in Cambridge, one of whom was a biologist specialising in these creatures which live in the deep Antarctic Ocean. The other was a computational biologist whose specialism was in genetics. I began to think about how different species of animal and plant life are sampled in science and utilised for our own means. I imagined a future in which every single life-form, human and animal, had been discovered and used as ‘data’ for human evolution — which is where the idea for Ophiux began. I imagined a high-tech medical room, completely automised which was being fed information from a diverse data bank sampled from the furthest regions of the natural world. The title of the exhibition is also the name of a speculative pharmaceutical company.

Obviously this is an imagined company, but based on some very real research. Does the level of reality or fiction that viewers take away from the work concern you? Or is it exciting to have it existing somewhere between?

Reality and fiction is often blurred, and I don’t adhere to these binary oppositions. Pharmaceutical companies wield enormous power and influence over the prescription drug and medical device markets around the globe. The staging of Ophiux is heavily influenced by the way in which these companies brand themselves; often making claims that seem far beyond their reach. Some of them even sound like they have named themselves after secret societies, like Ilumina — a company that produces genetic sequencing machines. Ophiux claims it holds the biological data of all lifeforms on earth, a claim which although seeming far-fetched, is something that is aspired for by scientific research. For example, since 2003 scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute have been on a quest to unlock the secrets of the oceans by sampling, sequencing and analyzing the DNA of the microorganisms that live there. They claim that they can ‘rapidly accelerate scientific discovery and unlock the secrets of DNA, leading to better solutions for the health of our planet, and ultimately, for all its inhabitants’.

How did you work alongside the scientists involved with this project? Did you have an overall idea of what you wanted to find out from them beforehand, or has this been quite an organic process?

I have been interested in this kind of research for a few years so it was great when Wysing arranged for me to meet scientists working in these areas. I went to visit them at their respective institutions and from there we had some really nice follow up conversations. Our relationships have developed as such that now they are giving me critique and advice about the presentation of the work.

Katrin Linse, a biologist from the British Antaric Survey has been kind enough to supply me with many hours worth of footage from an ROV (remotely operated vehicle) deep at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean where the strange landscapes of black smokers (underwater volcanoes) and completely unique ecosystems are found. This footage features heavily in the film which will tour to several arts and science venues after the exhibition has taken place.

Marco Galardini from The European Bioinformatics Institute has given me an insight into the computational technologies involved with the sequencing of an organism’s DNA and how scientists can use genetics to ‘programme’ life. Both of the scientists have heavily influenced the work, I can’t thank them enough: the project wouldn’t be what it is without them.

Do you find the computer programming of human biology a problematic idea for the future, or have you approached this from a purely inquisitive mindset?

Within most scientific practice and indeed all other areas, it seems as if everything has become a branch of computer science, even our own bodies probed, imaged, modelled and mapped: re-drawn as digital information. I think it is very problematic for everything to be reduced in this way; life is far more complex. Increasingly computation is taking over human knowledge and I think we need to seriously question this new landscape — examining the ethical implications of such technologies and who is governing them. Google Genomics already exists: ‘Big genomic data is here today, with petabytes rapidly growing toward exabytes’.

And finally, how do the film and installation relate to one another?

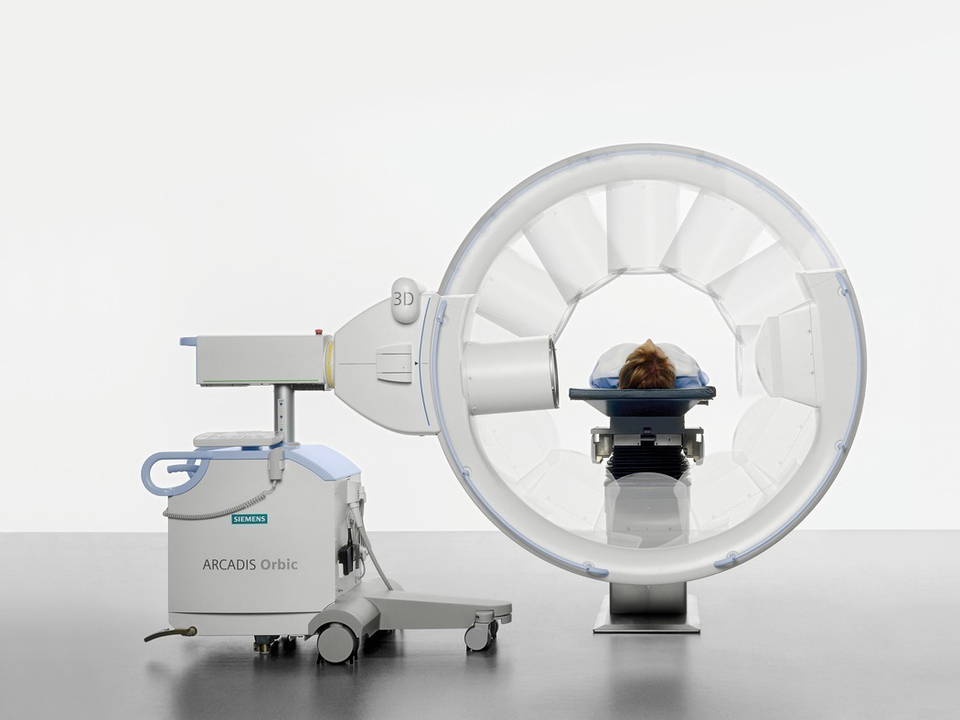

The exhibition installation includes larger than life-sized models of biological imaging machines including an MRI scanner and C-Arm X-ray machine. I see these sculptural pieces as defunct technologies, a mix of sci-fi and sci-fact left over from a time where humans once ruled. The film is a stand-alone piece based upon the same concepts, but adds deeper layers of narratives to the work overall. In the film the machines are very much ‘alive’ performing robotic surgeries and visualising biological data. The text based narrative which runs throughout the film is the voice of Ophiux whose mission it to ‘develop solutions to accelerate human health and evolution’.

‘Ophiux’ runs from 25 September until 20 November at Wysing Arts Centre. In conjunction, Holder will deliver a Study Day on Saturday 29 October, 2-6pm at Murray Edwards College as part of the Cambridge Festival of Ideas. Aspects of Joey Holder’s research will be shown at AND/OR Gallery, London from 14 October-12 November. The film has been co-commissioned by Deptford X and will premiere at their festival this month, followed by a tour to venues across the UK to be announced at a later date. All images: Joey Holder, found image (research), Ophiux, 2016