Can you tell me a little about the work that is showing at Johnen Galerie?

I am very happy to exhibit my new works in Johnen Galerie’s Marienstraße premises, before the space closes in a few months. The exhibition consists of three very distinct works in three separate areas of the space.

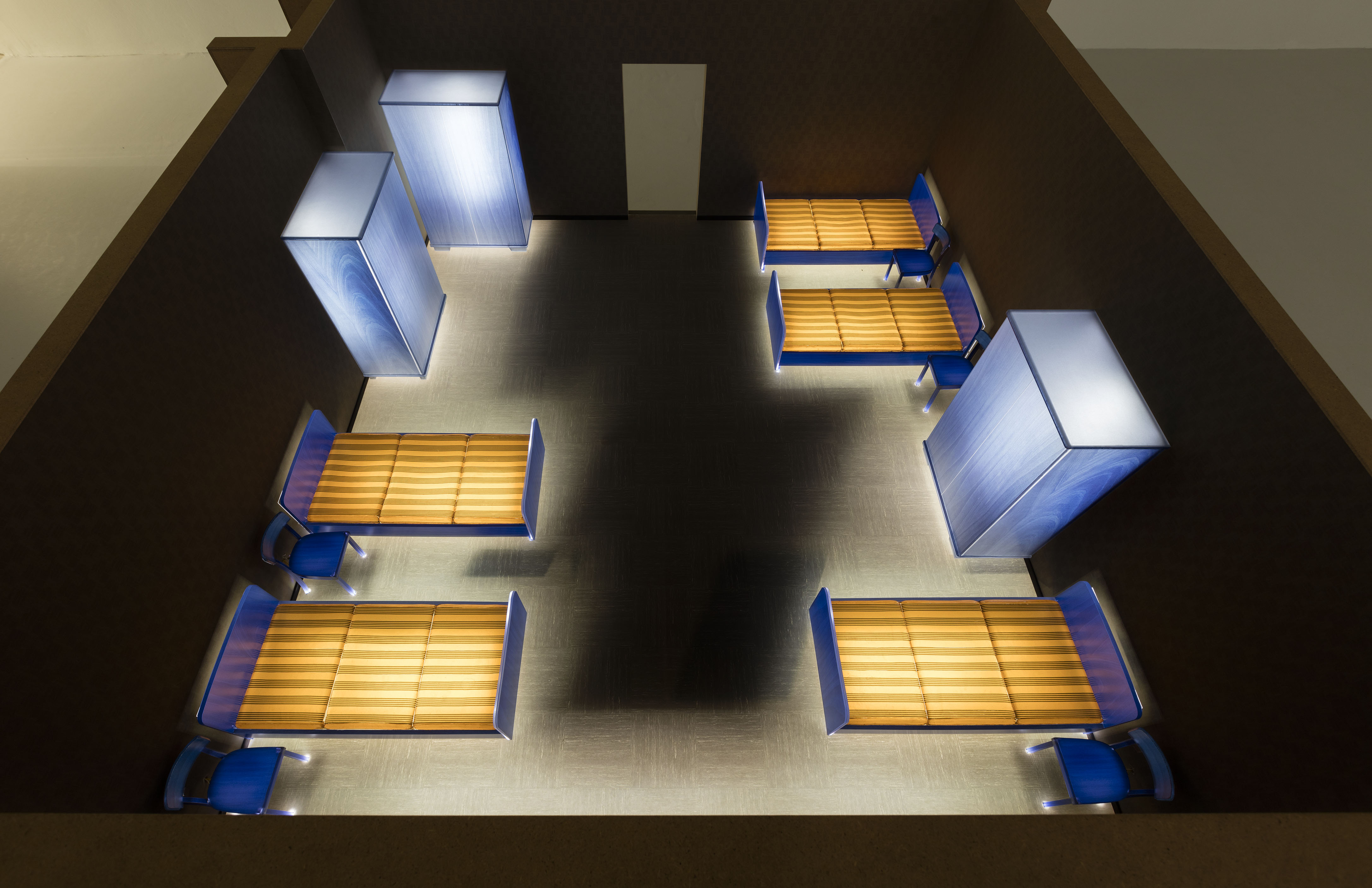

Upon entering, on the right hand side, Ziegelei (Brickyard) is installed in a small, darkened room. This is a re-creation of a vantage point I remember having as a child: looking out from among the racks in a shed used for drying tiles made in a nearby brickyard onto the houses of my familiar environment. In the dimly lit middle room of the gallery, I have installed a rather modest-looking box, which only on approach reveals a view into a lit up room with five beds, five chairs and three cupboards. The title of the work is Schlafsaal, 2013 (Dormitory) and it’s a 1:5 scaled model of my dorm room at my boarding school in Eastern Westphalia. The light-colour situation is negatively inverted. Through a small corridor visitors enter the very bright third room of the gallery. Taking up the entire width of the space, I have installed VSG-Gruppe (VersehrtenSportGemeinschaft), 2015-16 (disabled athlete group). The image of these six athletes, visibly amputated, sitting on a bleachers-like structure is an exact reconstruction as a life-size installation of small photographic print. The installation has the qualities of an enlarged photograph: the surface appears grainy and the outlines of the figures appear slightly blurred.

How did you come to the idea of childhood in your practice? Is this something that has always been of interest to you?

It’s quite true that, for some time now, childhood has been a central theme in my work. But to be more precise: memory is my central theme. And the further back a memory lies–the better! So, in a way, childhood is unavoidable.

You’ve spoken about exploring memories that exist as an image. Do you find that making these works takes you, personally, closer to the full memory or ‘emotional truth’ of the moment itself?

I don’t really think that I can arrive at a deeper level of knowledge by realising my memories. In my work, I’m especially interested in the vague, emotionally indifferent memories that are and remain incomprehensible, even after intensely working on them. I find it really appealing to put things out into the world that I don’t really understand myself.

Your three dimensional works often play with the effects found in photography. Do you see your practice as photographic as well as sculptural?

Neither…nor. I neither consider myself a photographer, nor a sculptor–and I am not a mixture of both. My work also has nothing to do with photorealism. I find it easier to say in a figurative sense: I create images. It’s true that photography is an important theme in many of my works, probably because the medium addresses the notion of memory in a particularly interesting way. Working in a three-dimensional way, in turn, allows me to question the medium of photography. Of course, I hope that in this way a third option presents itself.

Each of your works are produced by hand, and it’s been noted that they are very time consuming. Do you have a very strict process for making works? Do you know exactly where they are going in advance or do you tend to develop them more spontaneously?

Firstly, it’s important to note that I try to realise every image using new methods. It’s a very exciting moment for me in the process of creating a work, when I find out what technique, material and medium is required for the image. At this point the production method is clearly determined, which leaves little room for spontaneity.

‘Martin Honert’ is showing at Johnen Galerie until 28 May