Detail image of part of: Oscar Santillan , Solaris (noon) 2017 Inkjet print 100 x 120cm

Santillan’s Solaris (noon) 2017 is currently included in a group show at Copperfield gallery in London. We have the weights, we have the measures brings together multiple artists–aside from Santillan there is also Ewa Axelrad, Daniel de Paula, Marco Godoy and Ella Littwitz–to explore the relationship between culture, learning and geographical claims.

This particular piece by Santillan is complex and thoughtful. Not only is it technically complicated (as he goes on to discuss), he has also chosen a site which is loaded for a number of reasons–the main one being that it is it the site of both the new, and rather hilariously named, ELT (Extremely Large Telescope), and a past site of great significance for indigenous people. That this contraption has been designed to look towards potential cultures on other planets while squashing another’s far closer to home is an irony that is not lost on the artist.

His works tend to be multilayered and these important considerations on how cultures operate and people make their mark is often underscored by many different aspects–in this case, a technical approach to the material and subject matter. In the past, it has been humour, as in the 2015 work The Intruder in which in the artist removed the top one inch of rock from Scafell Pike’s summit, the highest mountain in England, to a mixed response of both horror and amusement.

I spoke with the Ecuadorian artist.

Can you tell me a little about Solaris (noon) 2017?

Solaris proposes the notion of the landscape as an observing subject rather than a passive object to be looked at; the possibility of a self-conscious landscape capable of reflecting upon itself.

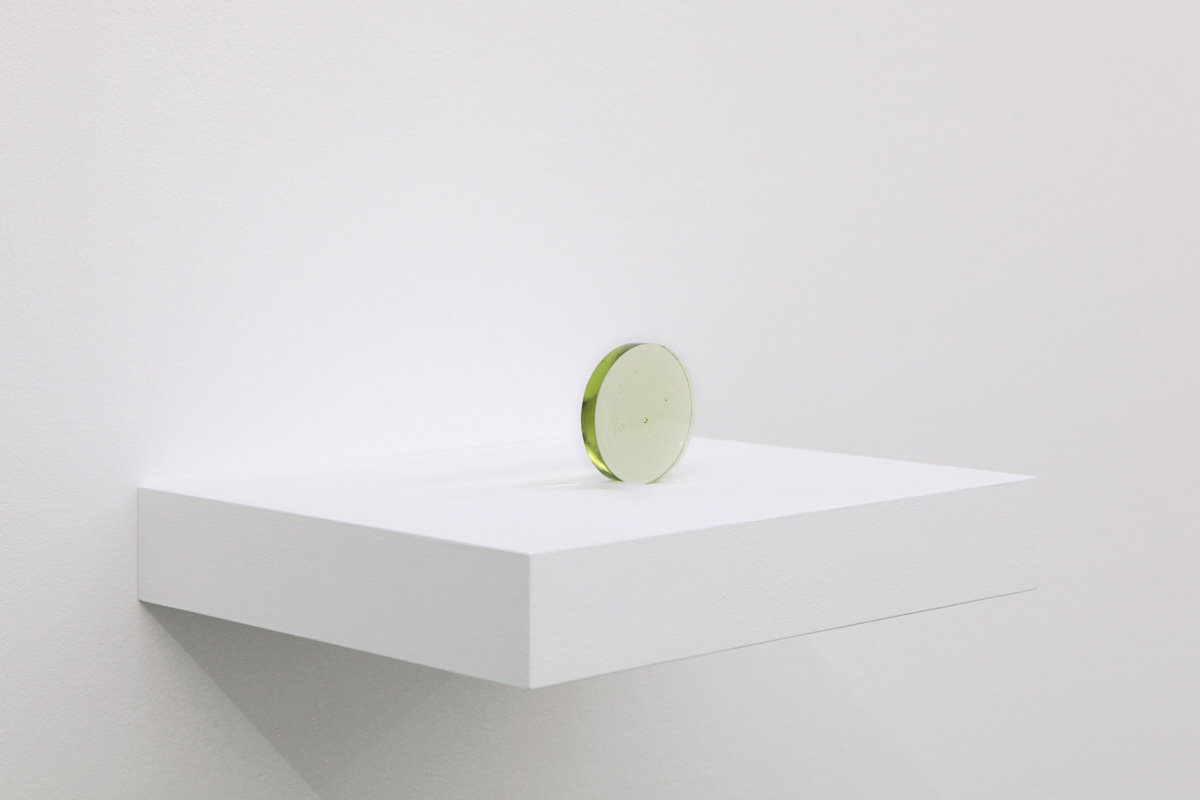

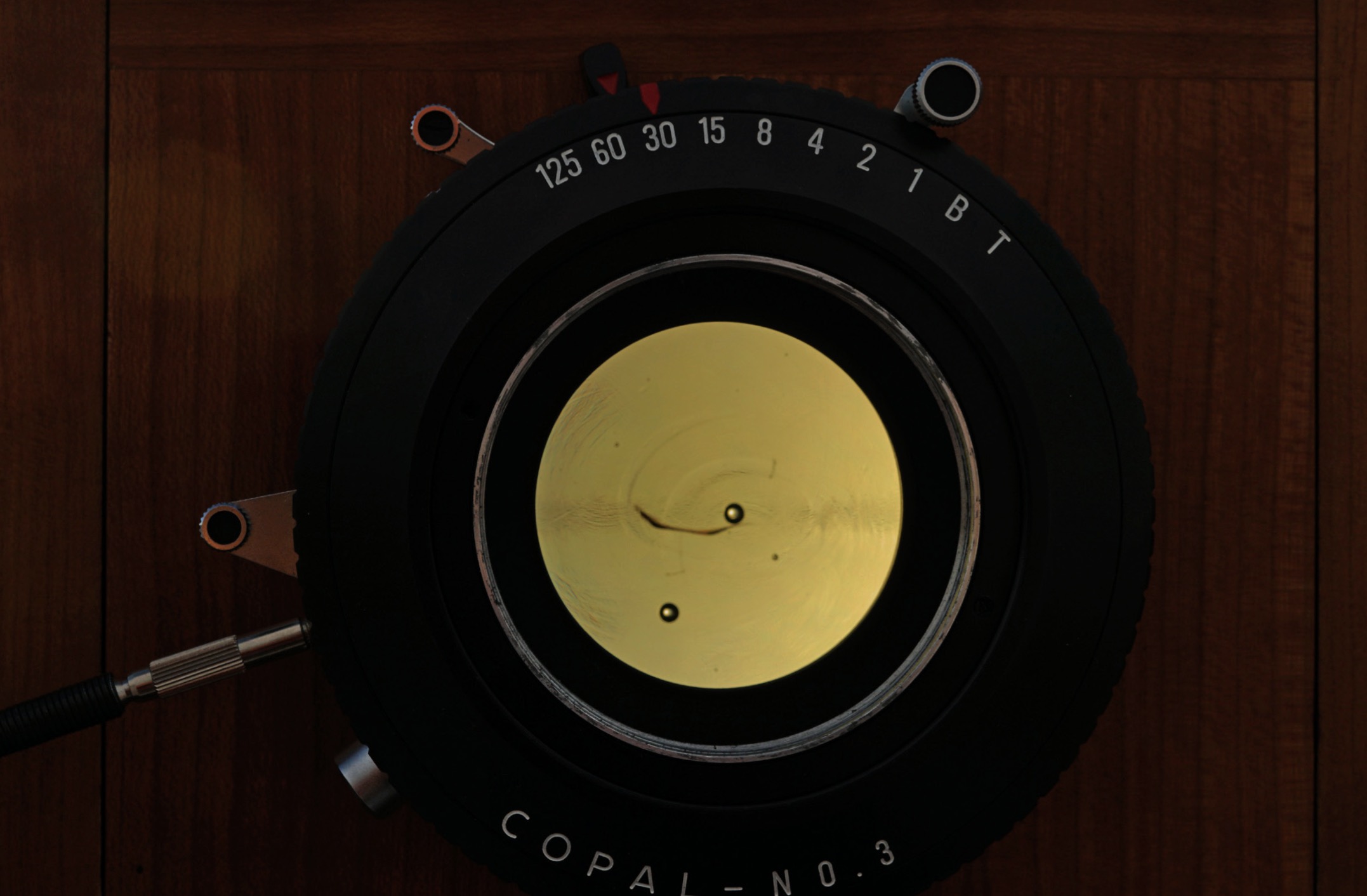

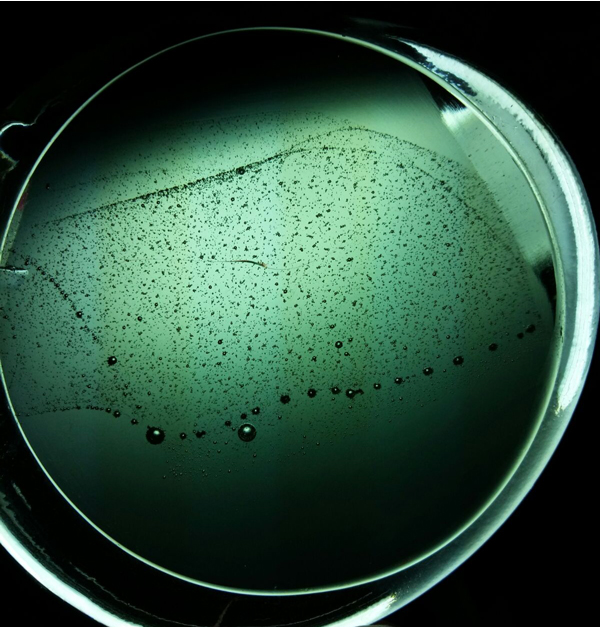

The Atacama Desert in Chile is the most arid place on the planet, therefore, its atmospheric conditions are perfect for astronomical observations. This immense territory has hosted many different human populations throughout history, including the Incas, and nowadays, impressive telescopes such as ALMA and VLT (Very Large Telescope) are installed there. At the moment the largest telescope ever built is under construction, which is known as ELT (Extremely Large Telescope). For Solaris I took desert sand from the ELT location and, by working with scientists and specialists, this sand was melted into glass that consequently was shaped and polished into a photographic lens. During my final journey to Atacama I used the lens to photograph the desert; in its most physical sense, the desert becomes an eye capable of looking at itself.

Solaris is evidently inspired by the sci-fi classic written by Stanislaw Lem in the sixties, which explores a potential type of intelligence that is not centred on a brain but rather emanated by the sea of a far-away planet called Solaris—a kind of self-conscious sea.

How did you first come across the site for the proposed ELT?

For some time now I have been in close dialogue with astronomer Frans Snik, who is part of one of the teams working for the ELT project. Those conversations were critical in igniting my curiosity.

Solaris, which was originally commissioned by MUAC (Mexico), is the first large project of an astronomy series that I will be working on. My hope is that the dialogue with Frans and other astronomers whom I have met in the last months, such as Steve Haveneers and Alejandro Farah, will deepen and expand into new projects.

There is a message in this piece, as in many of your other works, and it raises questions about how indigenous people and other cultures are, and have been, treated. Do you see yourself as taking a moral stance as an artist? Are these outright political works?

The scale of reality is not the scale of politics. I am deeply interested in expanding our sense of what is possible; of the limits of reality itself.

Being political right now, at least for me, is not about making the correct claims that the critical consensus of the art world expects; being political does not consist of adding more critical discourse or analysis into the public arena; being political is not about reflecting upon the obvious crisis of representative democracies; being political right now is about being able to expand our sense of what is possible, to show actual physical proof that unknown layers of reality exist.

History is often at the core of my work, although it is not a “History of the Past”, in the sense of pursuing an event that occurred, rather it is a “History of all the potential Pasts”, since I believe that the past is a material that is just as speculative as the future.

There is a humorous element to lots of your work, which is very powerful for some people and is somewhat lost on others—the most obvious example of this is The Intruder. Who, in the end, are you hoping to reach?

I hope to find viewers that care as much for the genitals of dinosaurs as for the invention of the guillotine.

You’ve taken inspiration from the self-conscious sea in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris for this piece as well as a very real, current piece of technology. Would say you’re more led by science fiction or reality in this kind of work… or do you enjoy blurring the two?

I try to think of the visible and the invisible, the real and the non-real, as equivalent terms rather than opposites. While I feel very close to Lem’s writings my work is not metaphorical. Indeed it is extremely physical, I see my work as the tangible evidence that elusive phenomena can be crystallized. This impulse is not a romantic one: recently curator Cuauhtémoc Medina described my practice, as “an investigation of the margins”, and those margins I believe reveal the limits of our senses, allowing us to consider a larger reality.

‘We have the weights, we have the measures’ runs until 29 July at Copperfield gallery in London. copperfieldgallery.com