Can you tell me a bit about I Sing of Armoires…, which is showing now at Sims Reed Gallery in London?

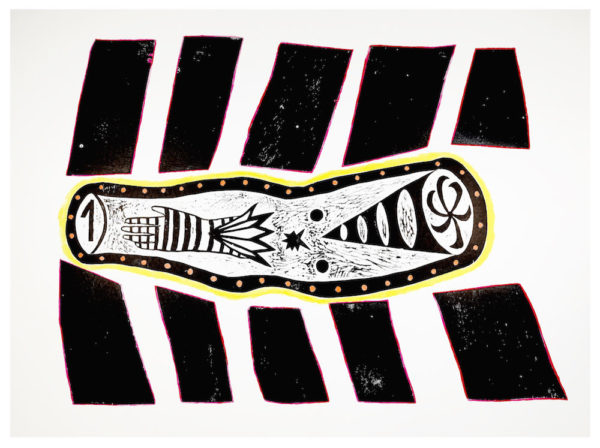

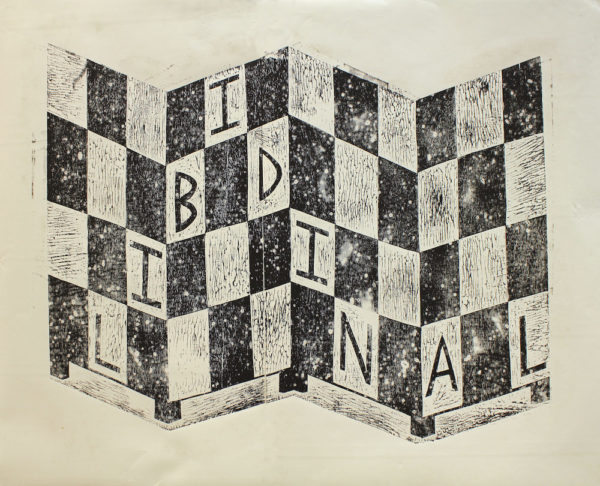

I Sing of Armoires… is my first solo show and I’m extremely excited about it! I will be showing a new body of work featuring imaginary furniture, weapons, enchanted spaceships and dreams of humanoid beings. Over the course of this year the theme of furniture began to emerge in my work, I wanted to use the block to imitate a three-dimensional object, creating a confused space somewhere between two and three dimensions.

I’m attracted to the theme of furniture as I enjoy the poetic rigidity of wood. Furniture is an effort to accommodate this material to hold and support the body. I like the way that a chair, say, implies the human form, almost becoming a surrogate body in itself. Magritte achieves this brilliantly in his painting The Balcony, a reimagining of Manet’s earlier version. Magritte shockingly replaces the women in Manet’s work with coffins. It is strange how effectively they substitute for the figures.

Many of my prints are shaped and in some way also echo my own body. In some sense they are the shadow of my person. The word armoire is French for wardrobe. It is derived from the old French word armaire, a large cabinet originally used for storing weapons. I see the woodblock in similar terms, as a sort of container for an image or idea, perhaps something powerful or unsettling like a weapon. Sometimes I feel the block is an alchemical device I’m using to capture some quality, a kind of talismanic camera that traps or focuses on images floating up from my unconscious.

We often–perhaps rather unfairly–think of woodcutting as a traditional technique primarily. How did you first come to working in this way, and how would you define the status of woodcutting in the twenty-first century?

Well, even a cutting edge technology can be limited to the conveyance of cloyingly conservative visions, while at the same time any medium has the potential to be revitalized. I do not use woodcut in an academic or traditional manner and luckily I’m self-taught and have not been burdened with the normative conventions of craft. The scale of my prints goes far beyond the traditional size of woodcuts, so in that sense they are melodramatic. Shaped woodcuts aren’t unknown, even Judd produced a few but the silhouette-like quality of my images implies that they are just as much props as prints, like swords hanging on a wall. I think we are living in an era when any medium can be taken up and used in a dynamic manner. Gert and Uwe Tobias are two artists who have succeeded in making some very powerful and contemporary woodcuts. The challenge is to stretch a medium, to make it do things that it couldn’t if it were to obey traditional commands.

You engage with many other ways of working also, including performance, video, sculpture and more. Do you see yourself as an entirely mixed-media artist or is there one that you feel most at home with?

It’s true that I’ve made works in other media, but I think that the fundamental difference is that with performance, video and sculpture my work is primarily ideas-driven–it’s form and structure is determined by a proposition. My woodcuts, on the other hand, do not set out to manifest a specific concept but open up a space for interpretation and suggestion. I like the idea that they can hold many meanings simultaneously. And they lay out an intuitive formal architecture that does not derive from a clearly thought-out objective. My prints come into being through the process of drawing and making whereas my performance work tends to follow more predetermined plans. With the woodcut I feel like I am working from inside the medium as opposed to using a medium to convey thought or language. Both ways of working have their own merits but I have recently come to feel more at home as a printmaker. There is something nourishing about the day-to-day engagement with a medium, the slow burn enjoyment of improving over a long period.

Discomfort is a recurring theme in your work and there are violent moments too with the inclusion of items such as guns. Where did this aspect begin for you?

I suppose some of the discomfort reflects my own discomfort as a person existing in the world. Printmaking provides a catharsis through which I can externalize or perform this anxiety to free up my mind. I like Chris Kraus’s description of desire as not being borne out of a lack but surplus energy–what she calls a “claustrophobia inside your skin”. So perhaps image-making is a way of emptying out some of this energy into the world. In that sense, there is a definite therapeutic aspect to my work.

I’m not sure the gun is necessarily a violent moment, I feel it is more a symbol of causality, the image of an irreversible action carried across time, like a pistol being fired. If it’s talking about violence it’s more of the sort which is embedded in the universe, the sort of energy that causes comets to crash into planets rather than a reflection on the politicised violence that we see taking place every day.

Your works feel claustrophobic but also economical with space. They aren’t cluttered despite at times feeling as though they need to burst through their outer edges. How do you strike this balance?

Space is an essential ingredient in my work. It can be stretched, compressed, pulled one way and back the other. My prints set up an exchange between the image and the space in which it inhabits (the paper). The prints address the space around them–I would say that Fontana or Knoebel have been of influence in this direction.

It’s important to add that this space isn’t that of the Renaissance (one-point perspective). It doesn’t present objects positioned in depth (unlike say the nature morte) it’s more like the space of the page; a flat, glyphic field. My images aren’t built from tone but emerge out of rhythmic marks and patterns that vibrate across a two-dimensional field–more like what you encounter in cave painting. A sense of movement is a quality that they can create.

If my work embodies balance it’s more the primordial balancing act of positive and negative space, dark and light areas, the sort of equilibrium that can only be achieved through the intuitive manipulation of form.

“I sing of armoires… ” runs until 29 September at Sims Reed Gallery in London. simsreed.com