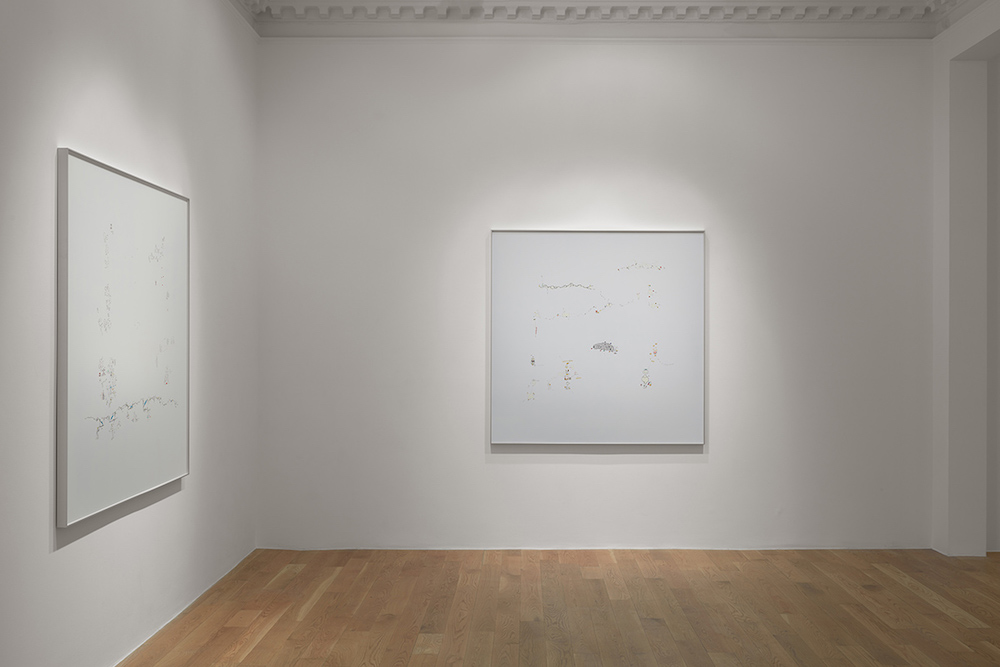

Italian artist, Gianfranco Baruchello is fantastically energetic. In his early nineties, the artist has just wrapped New Works at London’s Massimo de Carlo. His carefully handcrafted works focus on the idea of the gesture, and the relationships between the mind, ego and the contemporary external world.

Inferiority Complex, the beginning piece within New Works, indicates a new exploration into psyco-geography. How did your fascination with mapping out the innards of the intellect, and the workings of the mind in relation to ego begin?

The idea of the eye stopping to observe the mere surface of things has bored me since the 1960s, when I first started creating these openable and explorable objects. The voyage of my mind was guiding me in all directions, inside and outside, never one-way but always focused on fragments and emptiness. These Interiority Complex are female bodies that open up, not that much for the gaze but more for the harmonies of feelings and the desire to understand the complexity of the other: a little personal exercise that aims to leave to the side egos that are too monumental or cumbersome.

Could you tell us a little bit about the ganglions of connections? How is this idea realised in these works?

It is the first time that in my objects–which are thought as three-dimensional spaces–I transform the external transparent surface in another layer that challenges the gaze and the mind of the viewer. The gaze of the viewer finds itself in front of a space that incorporates and wraps him in. These spaces are created in order for this possibility to take place. If they had been larger they would have become rooms, if they were smaller they would have been dominated. The ganglions, as I called them are just possible starting points for the varied directional imaginary of our mental tracks: in front, above, below, on the side. The multiplicity of the images here function as an allegory of the complexity of the real, that we only see certain aspects of. The invitation is to imagine first of all a different way of seeing that starts from connecting and disconnecting all the logics and systems that work in a unilateral way.

You have traditionally seemed to distrust the veracity of language, do you feel that this is represented within these works too? Do you feel that exploring psycho-geography goes some way into making up for the inadequacies of language?

Language is not absolute, it is not ‘true’, and it is not the truth: it is an infinite practice, at the borders with the possible that can be thought and expressed. Though what the language says sometimes becomes system, reference, words with restricted significance. I am interested in exploring the possibilities of language that I constructed but I am also ready to risk. Every new work I make functions as a tool, a device to understand and test if my language is still working. I am not very sure about what you mean with psyco-geography. Though I can say that language is also made by feelings and affections more than just ideas and concepts. The complicity between all of these things produces something, physically and mentally.

Going back to your beginnings as an artist, could you tell us a little about how you managed to break away from your position at your father’s business, and how you came to realise that you needed to be an artist, instead of continuing with a traditional career?

It was that moment in time just after WW2, I was twenty years old. My father was struggling financially. I was a young Law graduate, a degree that at the time was meant to ‘open many doors’. It was quite clear what I had to do: try and help my family’s business and my father. But it did not last long. Although the factory I found to direct was working, my personal crisis came quickly and in the mid-1950s I already had paintings I made behind my desk.

On your return to Italy from New York, how did you find your artistic practice transition back into the context of Italy? Did you feel relatively free to pursue the art you wanted to?

After what I could call my American years, even if I went for many months at a time, not much changed–never definitely. I kept thinking that art was the way for me to build and create a tool and a language that went beyond the fashions and customs of the time, which in Rome and in Italy were far too prominent. With Paris instead the relationship never finished, I have had a studio-flat there now for forty years where I live and work when I can leave Rome. I walked my road on my own and I don’t regret anything. Between risk and opportunity I chose a third road that stands between the two and is far more full of risks.

All images: Robert Glowacki