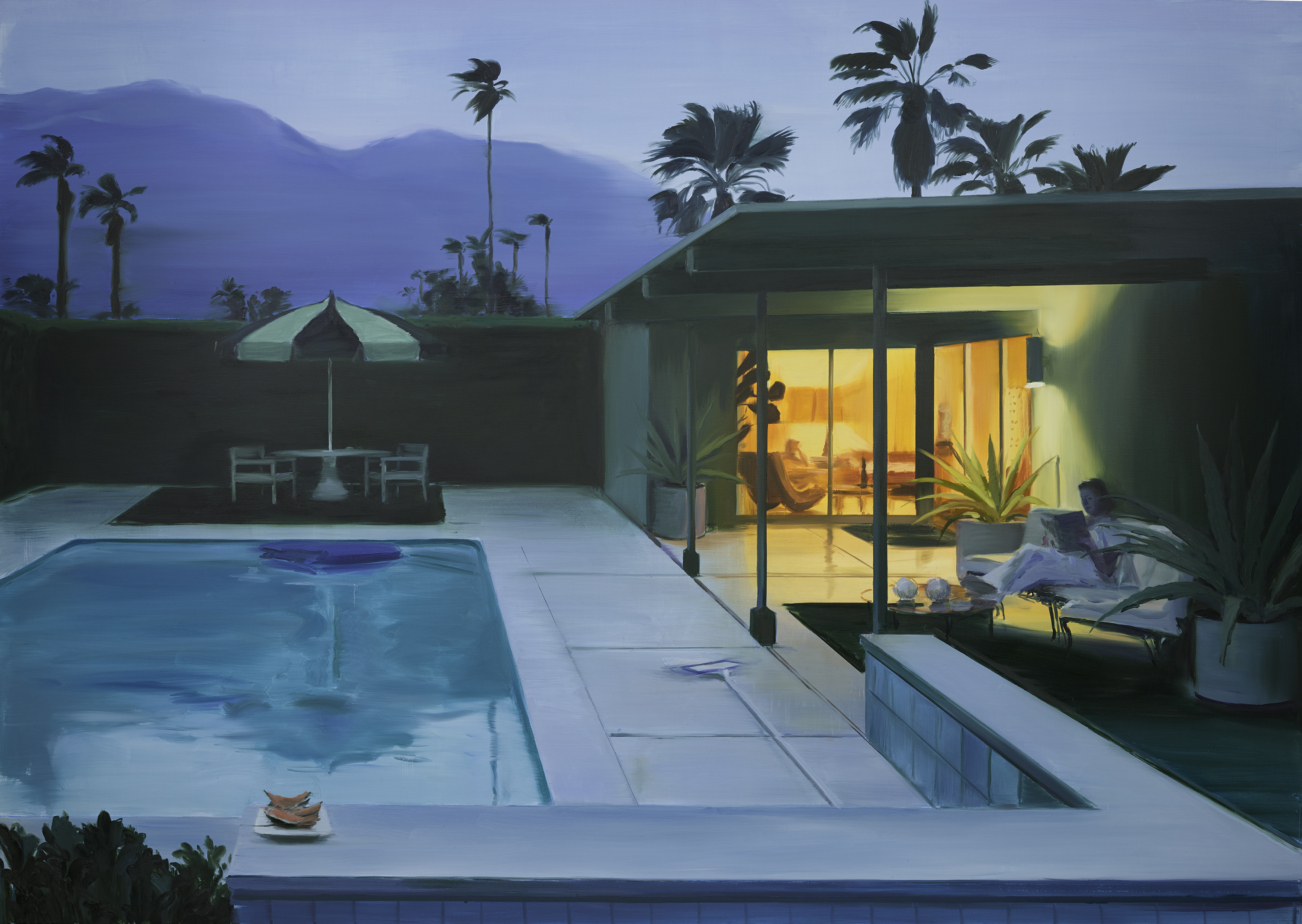

It is impossible not to be seduced by the paintings of Caroline Walker. Her seemingly effortless painterly style, which reveals strangely familiar environments exclusively populated by women, invite you to imagine yourself within the confines of her pictorial plane, and bask in the glow of her carefully calculated palette.

Her works are just as compelling on the printed page, something made clear in her new monograph, co-produced by Anomie Publishing and Grimm Gallery, which chronicles her prolific output since graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2009. Her various series, which include the dreamy modernist interiors of Palm Springs; the convivial environment of London’s nail bars; and her sensitive portrayal of female refugees living in transient accommodation, are presented as singular images and installation views, which give an idea of the enormous scale of many of her paintings, along with their more diminutive oil sketch counterparts.

Marco Livingstone’s introductory essay places Walker’s work within the canon of historical painting, be it the legacy of David Hockney’s LA swimming pools or the complexities of the female gaze as presented by impressionists Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. Further political contexts are offered up in Dr Rina Arya, concerning the intimate yet transactional nature of salons, and Andrew Nairne, who commissioned Walker to produce a body of work titled Home, which was based on the particularly sensitive subject of female refugees for an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge.

These brief texts punctuate the veritable flood of beautifully executed paintings, with each one inserted as a delicate half page, not unlike a bookmark. Conversely, some of these markers are devoid of any writing at all, and simply present a few of Walker’s scribbled notes or hurried sketches. In this way you always feel rooted in looking as much as reading, which is one of the luxuries Walker’s work affords, according to Livingstone:

“This is an art powered by, and giving permission to, the pleasure principle. I don’t mean that to sound like a trivial matter. During a period in which ‘aesthetics’ and ‘beauty’ have come to be seen as problematic concepts, ones that are to be pushed to the sidelines in favour of critical theory, disruption, subversion and irony, it takes a certain kind of courage for an artist to persuade us that this is permissible, even welcome, to yield fully to the pleasures of the senses.”

I have to agree—leafing through these pages is an absolute joy. A handful of additional zoomed-in details allow for an even closer examination of deft brushwork, which comes together to form strangely cinematic images that all seem to harness a powerful inner glow. Sometimes this is literal, as Walker presents the warmth of a living room seen from outside, or the artificial luminosity of a swimming pool at night. In other cases, there is simply something inherently and implacably vibrant about her pictures.

Although you could easily luxuriate in simply looking at these works for many an hour, Livingstone’s extended interview with the artist also gives valuable insight into her practice. They cover her interest in “unfashionable” historical movements such as the Scottish colourists, her rigorous approach to materials and process, and the influence of cinema. Given the scope of her subject matter and the boundaries she so often erects between viewer and subject, they also discuss her “interest in the voyeuristic gaze, or those boundaries between public behaviour and private space”. This encompasses her systematic approach to the Sunset series, which involved hiring a former Miss America contestant as a model to construct a broad, fictitious narrative, and the far more intimate process of getting to know the women portrayed in Home. In this case Walker explains her considerations, concerns and extensive research around the commission, which involved visiting a refugee camp in Calais and meeting with various London charities, and ultimately conveying the very real experiences of five different women.

Considering the distinctly female universe that Walker has created, it also comes as no surprise that Livingstone asks if there is any political agenda, or whether she has found a gender disparity in responses to her work. The artist explains that, “When I went to art school and I started making paintings in this vein, of figures in interiors, I was relying on friends who modelled for me, or taking pictures of myself. I did paint a couple of men along the way, but mostly it just seemed that it was my female friends who were available and who instinctively I was more interested in painting.” She goes on to explain a latter, more analytical approach to her own interests and ways of seeing, before quoting critic and feminist academic Lucy Lippard: “It is a subtle abyss that separates men’s use of women for sexual titillation from women’s use of women to expose that insult.”

It is a powerful statement that shows the extent of Walker’s critical thinking, but also highlights the incredibly sensuality she achieves without any direct allusions to nudity or overt sexuality—it’s a bit of a shock to realize how instinctually compelling her works are, despite the absence of the ubiquitous imagery we associate with sensuality and pleasure. Walker’s paintings offer something else altogether, and although it might remain ultimately intangible, it is nevertheless utterly alluring.