“Flirtatious” is a suitable word to describe Chen Fei’s paintings. The Beijing-based artist’s first North American solo exhibition, Reunion, has just opened at Perrotin in New York, nestled in a Chinatown panorama marked by local business signs covered with Mandarin text, and hipster-favourite bottomless-brunch spots. Chen’s pastel-coloured universe accordingly bats between the old and new, as well as the hip and traditional painting tropes from contemporary art and Western history—nudes, still lives, portraits and interiors proliferate.

“The Internet showed my generation that what we thought of Western art was totally different”

China’s socioeconomic ascent is key to Chen’s work, which reflects the country’s aesthetic tastes. In sprawling buffet paintings, Western-trained eyes may seek hefty bunches of grapes or carafes full of wine, but in Painting of Wealth or For Breadth and Immensity (both 2019), the fetes include mouth-watering red bean buns, bright-skinned yuzus, fat dumplings and juicy lychees, rendered in a flatness that Chen humorously comments on by asking me: “Is my apple’s sphere not a sphere?” He explores the common notion of flatness in Chinese painting, and the traditional artists’ eschewal of rendering daylight or shade, unlike Western masters who were fascinated by dramatic candlelit shadow effects.

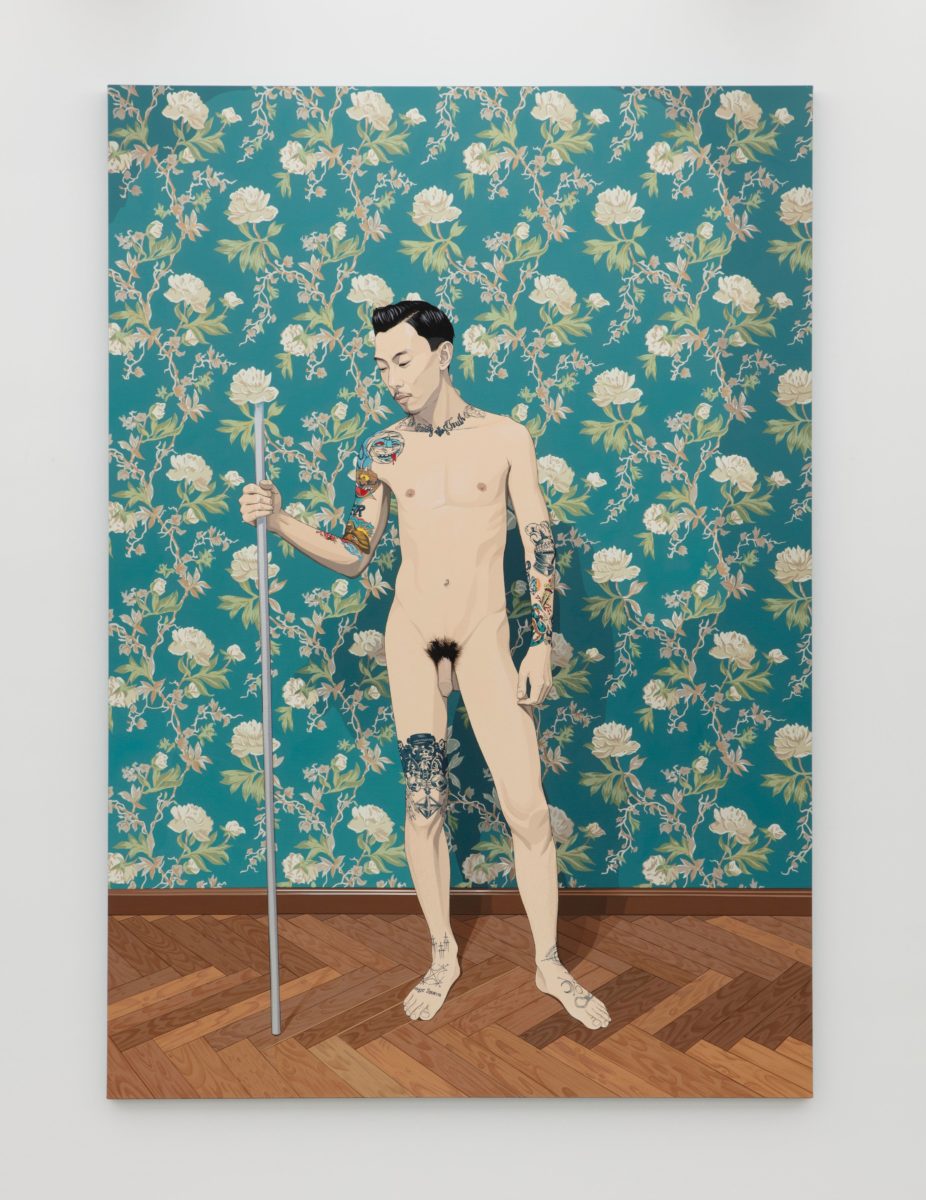

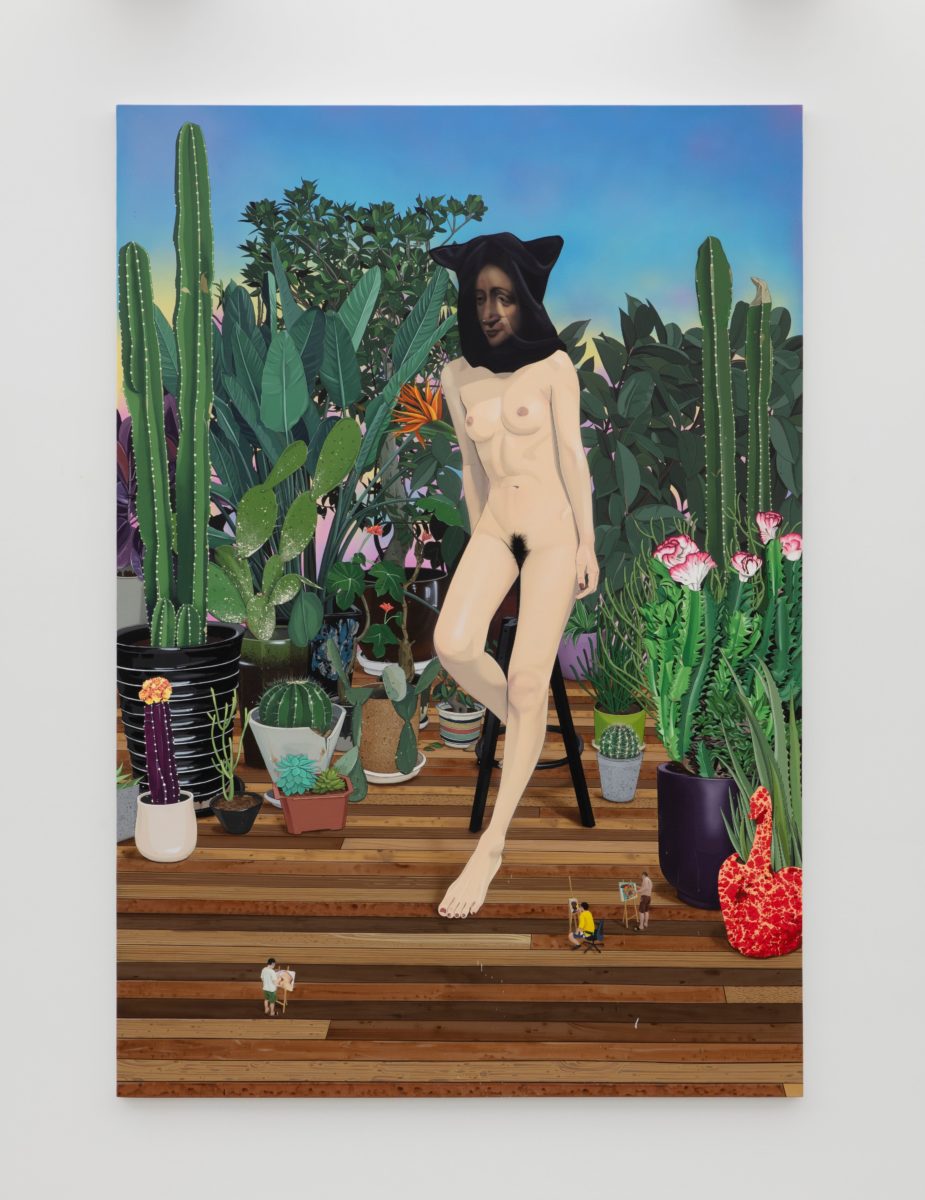

- Left: Big Model, 2017. Acrylic on linen, 290 x 200 cm; Right: Studio Portrait, 2018. Acrylic on linen, 290 x 200 cm

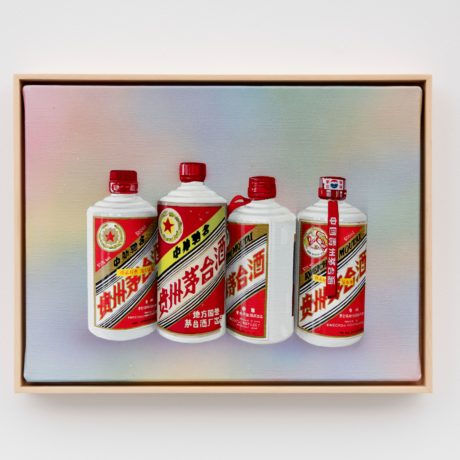

Two My Morandi paintings (both 2019) are a tongue-in-cheek twist on Italian still-life painter Giorgio Morandi’s powdery renditions of Mediterranean feasts, which are full of wine bottles and fruit bowls. In Chen’s version, half-consumed soy sauce jars, rice vinegars and soju bottles encapsulate typical Chinese kitchens, reflecting a traditional domestic lifestyle and giving some insight into “their amiss users”, according to the artist. Remaining Value (2019) is also humourous, placing Merda d’Artista—another Italian maestro, Piero Manzoni’s, notorious, faeces-filled tin can sculpture from 1961—next to various types of fertilizers used in agriculture, coffee production and farming.

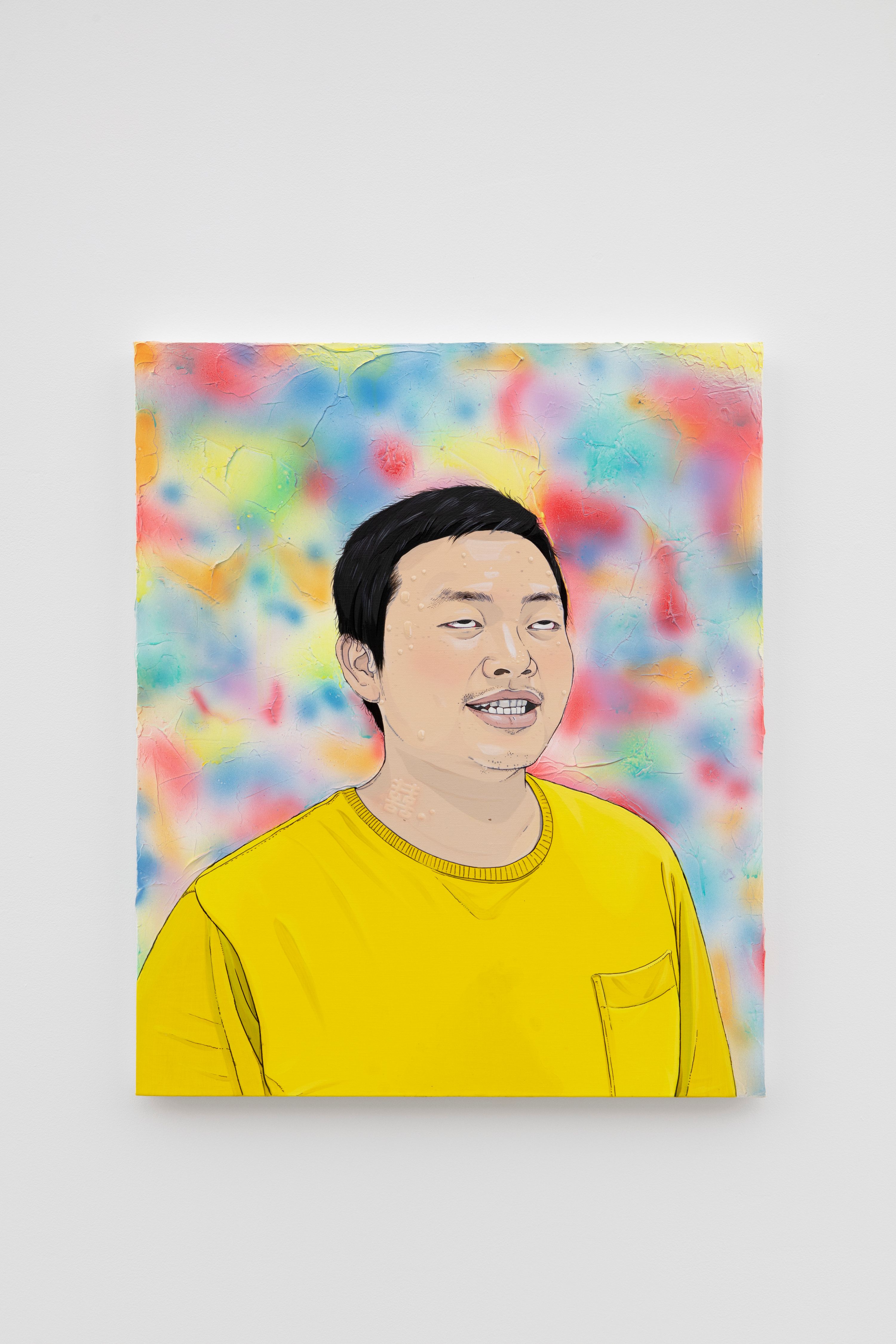

Chen is at the forefront of a wave of artists who emerged in the era that followed China’s one-child policy and the economic boom that dotted the county’s metropolises with Louis Vuitton stores and starchitect-designed contemporary art museums. His visual lexicon borrows cues from a society committed to its cultural inheritance, yet fuelled by the West’s representation of the body and its sense of spatiality. “Our learning of Western painting always started with France, until the education turned to the Soviet Union after World War Two,” says Chen, standing in front of Big Model (2017)—a life-size acrylic on linen depiction of a tattooed nude Chinese man in an elegant, David-like contrapposto in front of a turquoise, heavy floral wallpaper.

- Left: Painting of Opulence, 2018. Acrylic and gold foil on linen mounted on board Unframed: 43 x 120 cm; Framed: 65 x 142 cm; Right: Painting of Harmony, 2019. Acrylic, gold and silver foil on linen mounted on board, 100 x 200 cm

Until the mid-nineties—a breaking point that the Chinese refer to as the “opening of the market”—the access to Western art remained strictly limited and political. “The Internet showed my generation that what we thought of Western art was totally different. Physical postures [such as the one assumed by David], which we grew up considering to be polite, we later realized are art-historical,” adds the artist while petting my dog, who has tagged along and unexpectedly matches a few canines that Chen has placed in his works, such as the mammoth-scaled, Painter and Family (2018). The image shows the artist and his family posing at his studio, populated by paint tubes and artist books with spines emblazoned with names such as De Kooning, Tom of Finland and Luc Tuymans. The work recalls Las Meninas, but the innuendo stops there, according to the artist. Similar to Velázquez’s, Chen’s gaze is subversive; however, the thirty-six-year-old notes that his only direct homage to the seventeenth-century painter is his own presence in the work. “Icons of Western painting are always in the back of my mind due to education and the media, but I never seek or construct direct references.”

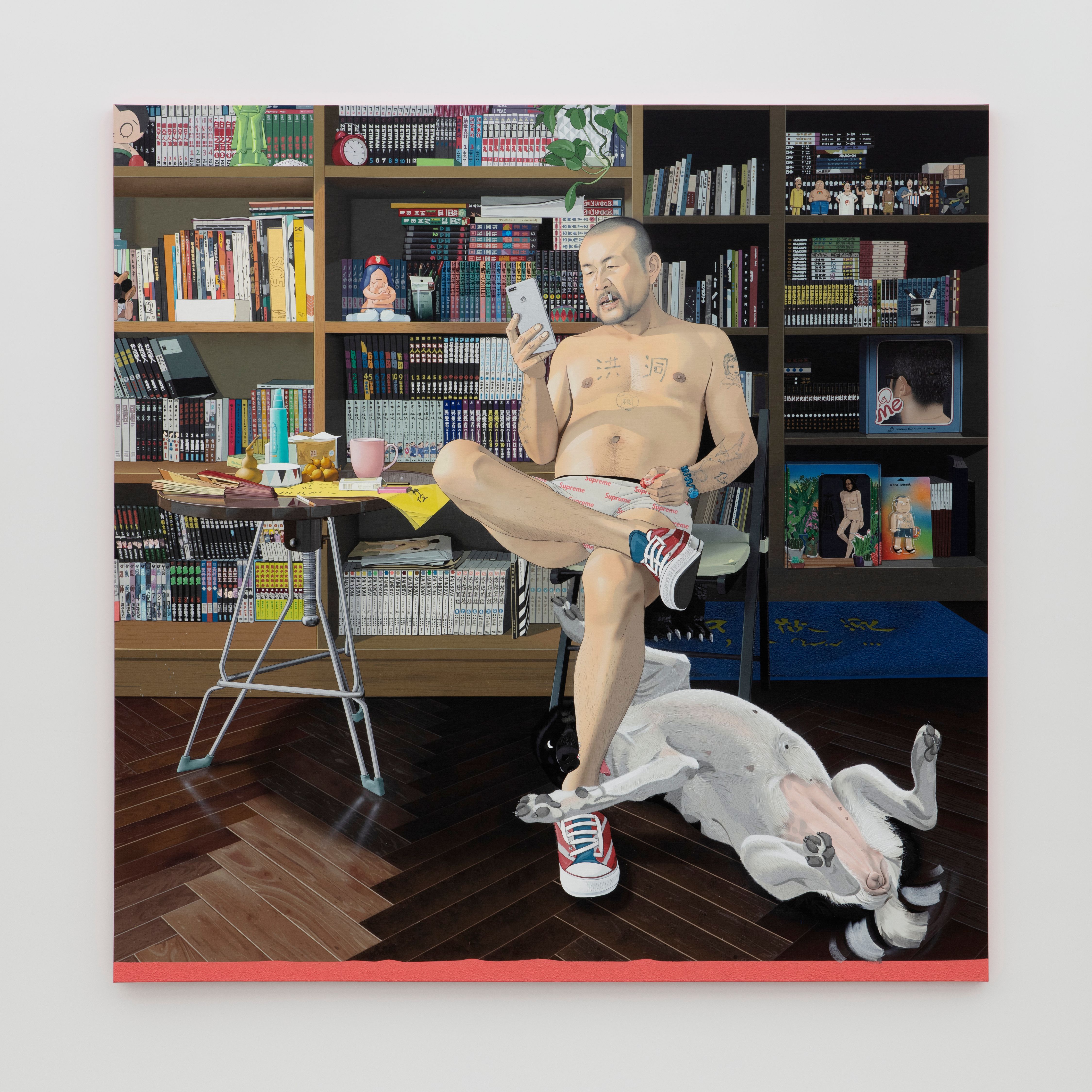

Chen’s own dog makes a cameo in Cousin (2019), which shows Fei donning nothing but Supreme-branded underwear and Converse sneakers while checking his Huawei smartphone. “I thought about painting myself with an iPhone, but I wanted to prompt viewers, especially those in the United States, to think about what Huawei politically means today.” Behind Chen is his personal library from his own Beijing house, consisting of books on art from a broad geographical range and time period, as well as his personal collection of sofubi: Japan’s highly sought-after soft vinyl collectible toys that he is an avid fan of.

The painting is a stark representation of the artist’s merging of public and private, East and West, real and fiction. Frozen in an ethereal, mundane moment, in which Chen swipes through his smartphone in his underwear while his dog chews his ankle in his library, the life-size painting bridges the candidness of a private moment with the accepted historical canon of art in the backdrop. When I ask him about the dog’s wagging tail, which shows off his loose brushstrokes unlike any other painting on view, he refers to manga. “Before manga built its visual language, two lines on both sides of a hand did not mean waving,” he tells me, “and this is my way of linking myself back into art history.”