Writer and educator Karen Wong on Dominik Tarabanski’s ‘Roses for Mother’, currently on view at WSA, NYC.

During the hundred years of the Dutch Golden Age, flower paintings emerged as a genre of delight and desirability. The burgeoning middle class generated a demand for a dynasty of skilled painters. They infused religious and philosophical meaning into highly organized depictions of dozens of floral species. These arrangements felt abundant and wild, bursting at the seams. Each blossom is lit with dramatic ambiance and vies for attention against sumptuous velvety backgrounds.

One of the sought-after still-life painters was Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), who began her illustrious career at fifteen and worked well into her 80s. Atypical of the period, she took the cut flowers out of the vase and placed the drooping stems on a stone slab, creating seemingly casual yet compelling compositions. One can trace the tension between the organic state and the obsessive control of Ruysch to the present-day artist Dominik Tarabanski and his photographic series Roses for Mother.

From 2018 to early 2020, after finishing his day job as a fashion photographer, he was left with the vestiges: unwanted flower displays, plastic bags, metal clips, gaffer tape, fruit nets, rubber bands, and twist ties. With these materials, the photographer pivots to sculptor, substituting his animated human body for a withering floral object. Like the still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age, Tarabanski constructs artful tableaus of beauty that belie an additional reading of melancholy and isolation. Leaning into an aestheticized anthropomorphism, he tapes and clips his subjects like a model of yesteryear. Tarabanski contorts, stretches, and molds his flower characters with humor and pathos, reflected in sagging petals like bowed heads shedding tears.

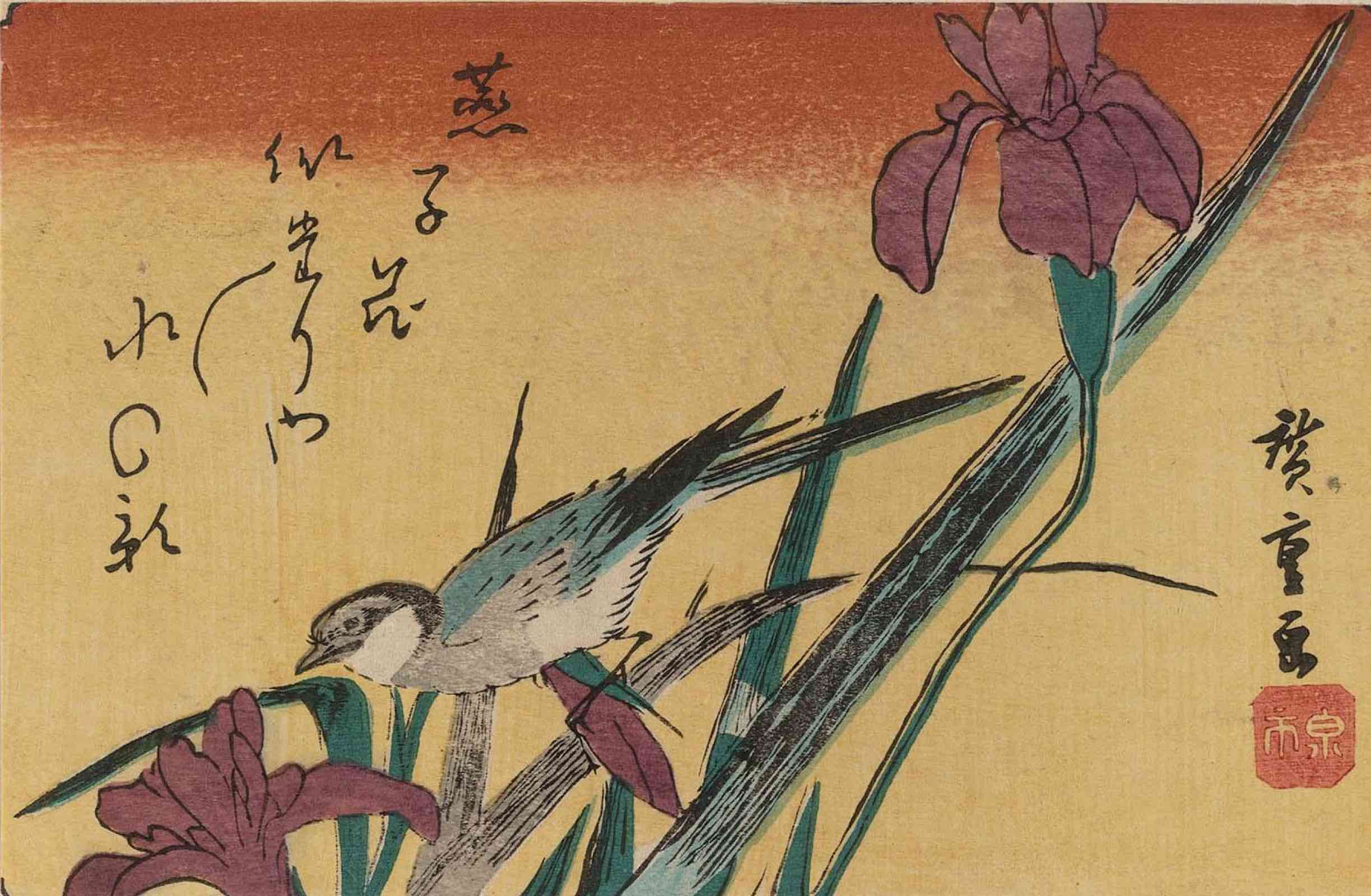

Tarabanski’s ability to choreograph his flower subjects recalls the work of Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), the last master of the ukiyo-e tradition. Hiroshige’s woodblock prints and paintings often depicted flora, fauna, and landscapes of his travels. In his renderings of branches, birds, and fishes, Hiroshige employed strong diagonals that produced a sense of urgent movement. He was undoubtedly instructed by the tradition of ikebana (making flowers alive), emphasizing the totality of the floral specimen. Having spent significant time in Japan, by osmosis or deliberate homage, Tarabanski uses a minimalistic language like Hiroshige, highlighting the slant of a leaf or the angle of a twig. His photographic results eschew the symmetry of classical flower arrangements for something stranger and operatic.

One usually doesn’t associate sounds with flowers as foliage is silent in its ability to convey a range of dispositions. German artist Isa Genzken defies this broad assumption in her series of monumental public sculptures, Roses and Two Orchids. Three-story-high steel structures clear their throats and announce, “I am flower, see me roar.” By isolating each floral stalk and concentrating on nature’s architecture, Genzken achieves a sentinel-like authority through towering heights. Tarabanski also leans into the flower’s structure and engineers a voice by manipulating his specimens as puppets — stems outstretched, buds singing in unison, and a bloom calling out for love.

The enchantment of Roses for Mother is the ritual before Tarabanski snaps the photograph, an archival product of an arduous creative process with numerous false starts and finishes. These diorama meditations require him to possess a variety of skill sets; perhaps the most natural one is akin to that of a fashion designer. Key to the trade is the sculpting technique of draping fabric over a mannequin until a form materializes, such as balloon trousers or a couture dress. Tarabanski sorts his day-shoot remnants and spends hours nipping and tucking his flowers with clips and tape.

In New York 2018, a wine cork is a counterweight for four pods of tiny floral spikes of Banksia hookeriana, a well-regarded blossom in the cut flower industry. Minute rubber bands hold the twigs in place while Tarabanski draws viewers’ eyes down to the roots with a single unopened Cyclamen bud. The artwork suggests that all life is a balancing act.

The tortured composition of West Bengal 2020 features arcs combating verticals as a shriveling Etlingera blossom stands in for a fading sun, all while the cantaloupe moon readies for orbit.

In Paris 2018, a metal clip holds together an unlikely pair — a Medinilla magnifica with regal leaves embracing the delicate Lilium candidum. The Medinilla’s stork-like stance protecting the foundling gives rise to the motivation of this series: a son’s bond with his mother.

Written by Karen Wong