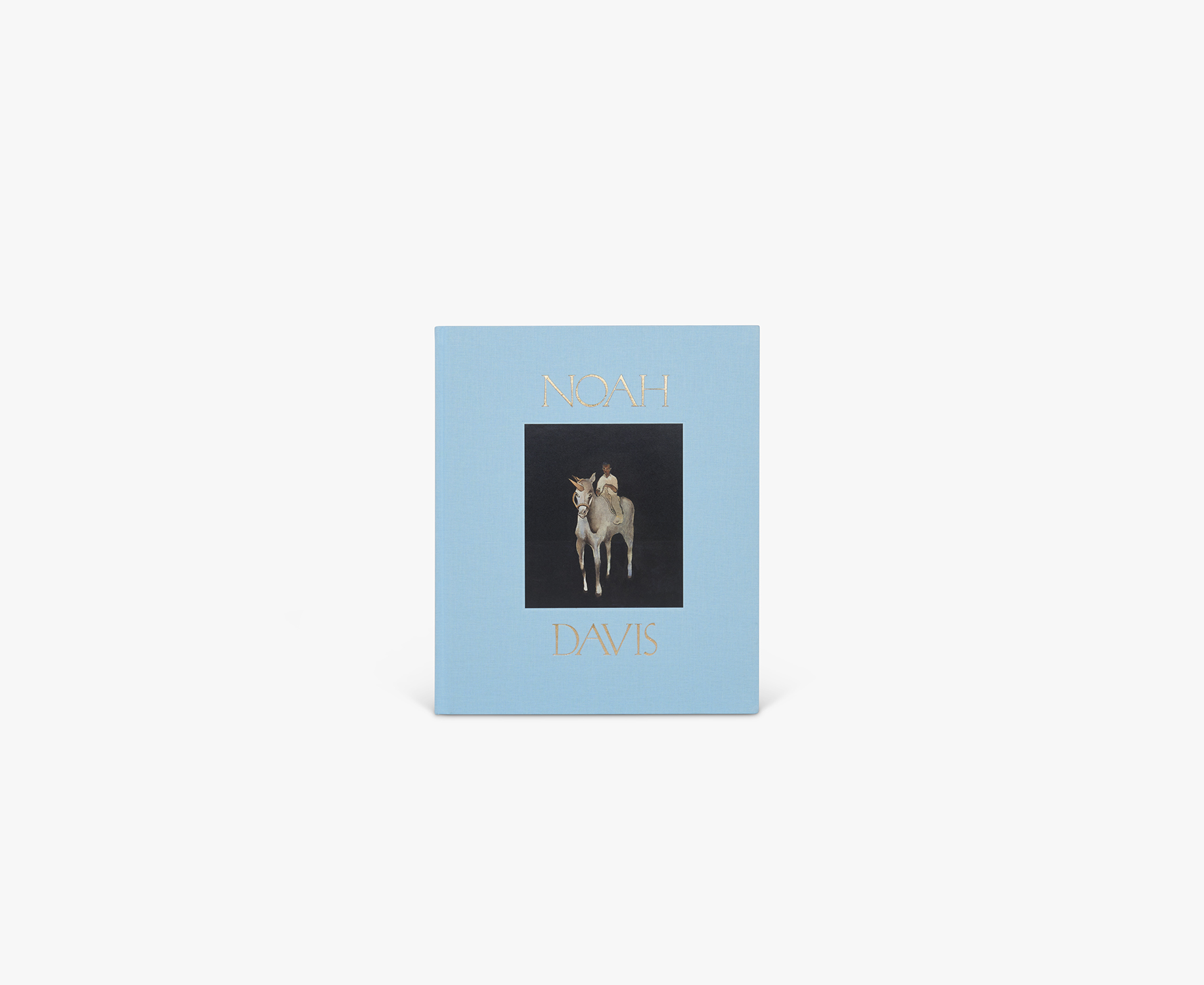

On the cover of a new monograph about the late American painter Noah Davis, a man sits on the back of a unicorn, a pose otherwise reminiscent of traditional depictions of masculinity, commanding and imposing. Yet the 2007 painting, titled 40 Acres and a Unicorn, shows the pair shrouded in darkness as if emerging from a dream. Though not a self-portrait, sandwiched between gold letters spelling Davis’s name, the suggestion is of the artist as a kind of mythic traveller moving between worlds.

Davis died in 2015, aged just 32. This book is authored by his friend and collaborator, curator Helen Molesworth, and must reconcile this fact with the revelatory nature of his achievements; it follows on from a show of Davis’ paintings at the gallery’s New York outpost at the start of this year, and while both contend with the subject of loss, their substance comes from all that Davis left behind: a comet trail of artworks, exhibition outlines, ambitions for his friends and community. As Molesworth writes, “It is a privilege to leave such traces, and it is an honour to tend to them.”

Throughout the book, Molesworth returns to the personal nature of the task before her and others who survive Davis. Rather than navigate his career in a straightforwardly linear fashion, she instead divides the book up through seven interviews with friends of his, including artists Deana Lawson, Venus X and Henry Taylor, whom Davis met at different stages of his life. These, she says, are the people “who knew and loved Noah long before I met him”, and it is through the prism of their perspectives that a sense of Davis emerges.

That is not to say the book doesn’t operate as a traditional catalogue. The separate conversations are divided up with plates of Davis’s paintings, arranged in chronological order. But alongside the interviews themselves, personal snapshots prevail––Davis painting in his studio or goofing around with friends, hanging out with his wife Karon, or carrying his baby son, Moses. The critical appraisal of his work as a painter is interspersed with and inseparable from memories and anecdotes about him as a person, an artist, but also a brother, friend, father and neighbour. Being all these things at once mattered to Davis.

“Davis knew how the art world privileged certain voices, certain perspectives, and understood the lie of universality”

It is a multiplicity that explains the nature of his atypical legacy, spanning both artworks––paintings, which form the focus here, as well as drawings and sculpture––and a pioneering arts space, the Underground Museum, which he founded with Karon, primarily for his friends and family. Today the Underground Museum is well known, with the likes of Barry Jenkins, Solange, Angela Davis turning up to shows; but before it cemented that reputation (with the help of his wife Karon and his brother, artist-filmmaker Kahlil Joseph), it was just Noah’s dream, a set of keys and a few vacant shop fronts. To understand it properly, Molesworth explains, you need to understand who Davis was: “the deep DNA truth of Noah was that he was first and foremost a painter”.

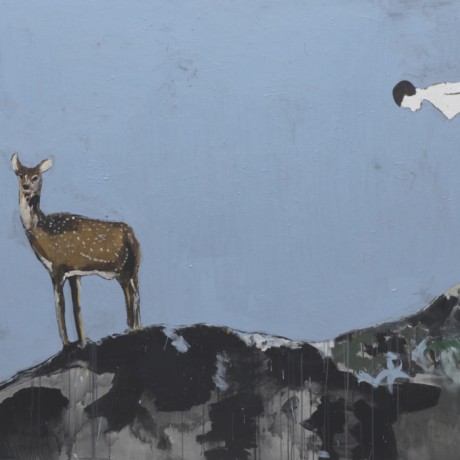

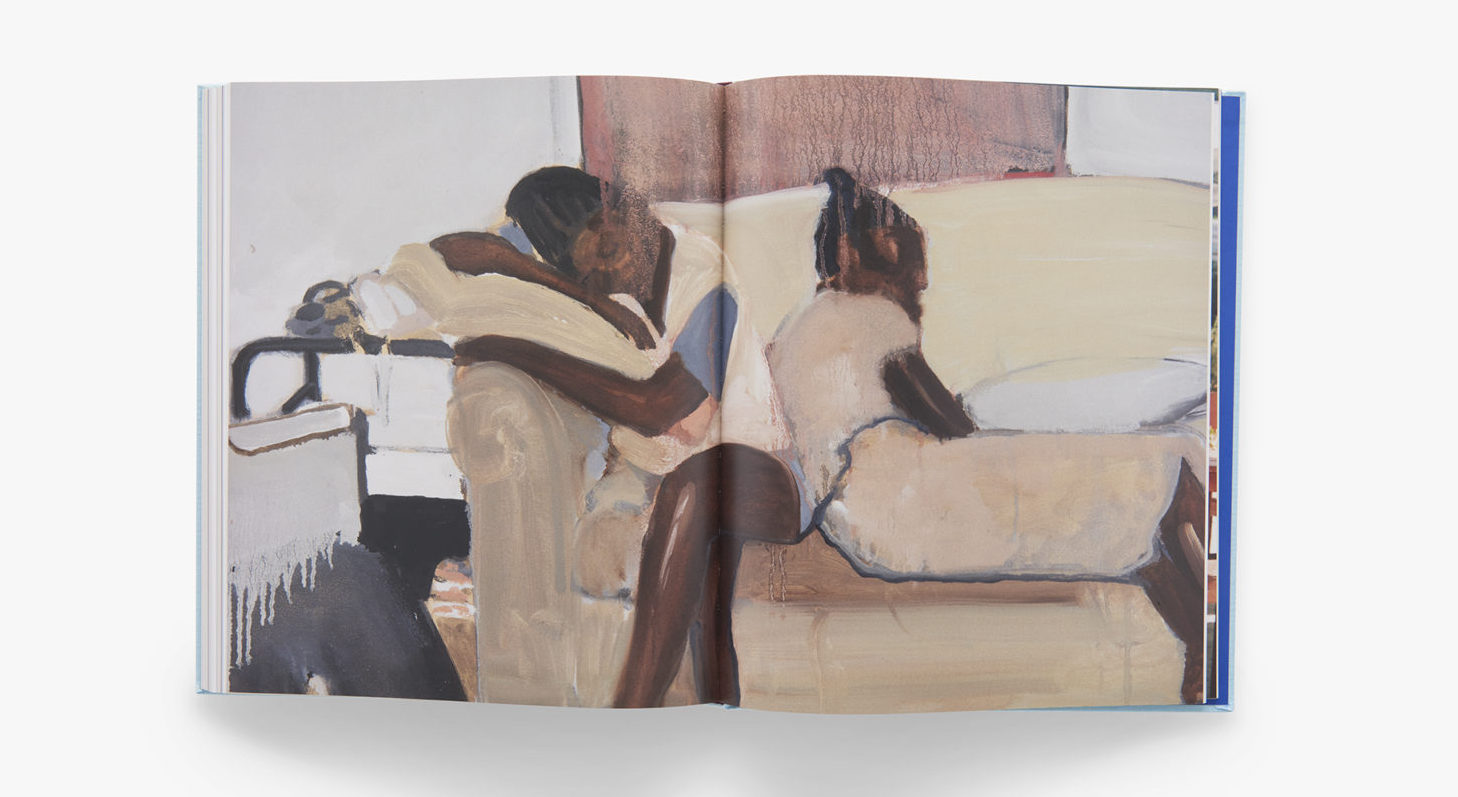

Getting to grips with the paintings is a central pleasure of the book. Davis was deeply knowledgeable about art history, able to intimate towards numerous, varied references while making them new. In his hands, painting is a medium with radical potential, and he used it to blend ideas about figuration and abstraction to create widely resonant work. As the years progress, motifs emerge: his figures are often depicted alone, suspended like the unicorn rider in space. In busier scenes, a detail or surface pattern—a pair of geometric leggings, some bathroom tiles, a striped wallpaper—will break free from the rest of the canvas, as if insisting on a life of its own. There’s a signature atmosphere too; things are always a little off-kilter, as if to look at the world through Davis’s eyes is to see what is here, and what is elsewhere.

The Underground Museum was established in the same spirit as these formal and aesthetic concerns in Davis’ painting, working both with and against art historical tradition and its codified ways of doing things. Davis knew how the art world privileged certain voices, certain perspectives, and understood the lie of universality. When he set up his own museum in Los Angeles it was decidedly elsewhere, and deliberately so, in Arlington Heights, a historically working-class Black, Asian and Latinx neighbourhood ill-served by the city’s arts institutions. He wasn’t trying to replicate what had gone before.

And where Davis went, others followed. Soon, the UM became a centre, not just for those in and around Arlington Heights, but for scores of artists, filmmakers and musicians based all along the West Coast and beyond. It offered exhibitions, but also talks, events, wellness activities. It was “Noah’s Ark”, chuckles the artist Henry Taylor: “motherfucking crazy but he just did it.”

“Things are always a little off-kilter, as if to look at the world through Davis’s eyes is to see what is here, and what is elsewhere”

To turn back to the painting that graces the book’s cover, Forty Acres and a Unicorn (2007), it takes its name from the Civil War promise of land and a mule to families freed from slavery, a radical pledge but one that was never realised, as much of the land confiscated in the South was returned to slave-owners.

In his painting, Davis simultaneously shows this promise for what it was––the stuff of legend––and for what it symbolised: hope, the space to prosper, emancipation. Picturing the world like this, both looking at the one we’ve inherited and turning away from it, towards something better, is at the core of everything Davis created. Where his paintings left off, The Underground Museum continues. It is through these twin bodies of work that Davis’ legacy operates, creating space for change on earth and for magic in the beyond.

Noah Davis

Edited by Helen Molesworth. Published by David Zwirner Books / The Underground Museum

VISIT WEBSITE