Jon Serl had many lives—even names and characters. The late 20th century American painter grew up with vaudeville actor parents who put him on stage at early age and dressed him in costumes. Like a puppeteer, this knot of a blessing and a curse holds the strings of his enigmatic painting practice.

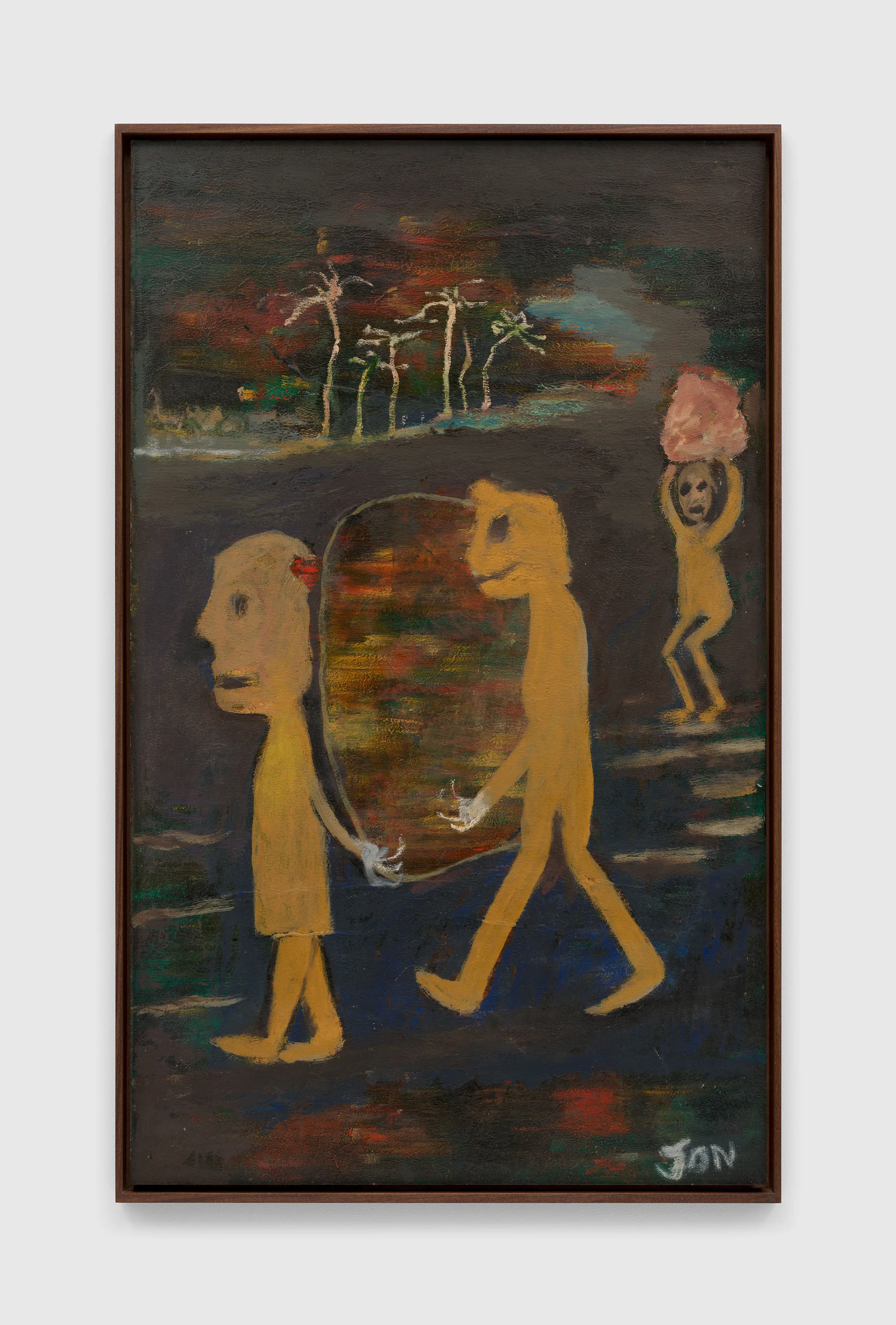

Between holding onto the reason and letting the imagination loose, Serl who throughout his life had other names like Jerry Palmer and Slats painted trivial daily endeavors in unusual ways. David Zwirner’s exhibition No straight lines which artist and Serl’s good friend Sam Messer curated to pair his friend’s work with contemporary painters revitalizes the artist’s psychologically complex take on the mundane. Next to paintings by Louis Fratino, Dana Schutz or Katherine Bradford, Serl’s villagers carry shopping bags, frequent the local church, or at times commit to indescribable feats. Their manners and activities, as well as Serl’s approach to figuration, feel like they belong to the 19th century Eastern Europe. They in fact depict American west, particularly Lake Elsinore where the painter lived most of his life in a self-built shack.

Courtesy David Zwirner

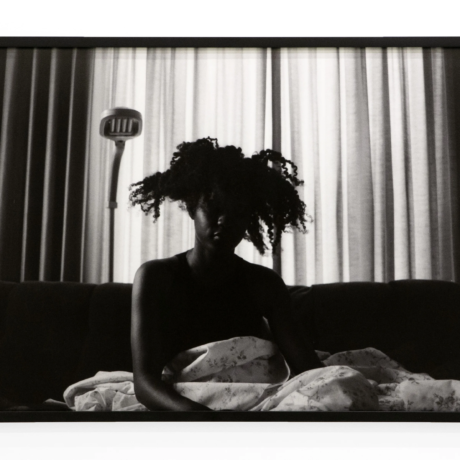

The detached eye of an introvert adds a veil of imagined relationships amongst Serl’s subjects, as if he never engaged with his figures but attributed them roles. Messer’s portrait of his friend, titled Even my dogs know that (1993-2024), possess a similarly willing unknowingness, a decision to leave the door ajar into a dim room. The gallery’s Upper East Side location which is housed in a historic townhouse operates as its own stage. An untitled portrait from the early 1980s holds the potential of an auto portrait. The clown-like face is powdered with colorful lips and solemn eyes, alluding to the archetype of the sad Pagliaccio. The earthy-toned painting which holds a thought bubble-esque lightbulb lit on its top right corner is mounted atop a marble fire place between two ornate wall moldings, like an altar or the ghost of a former inhabitant. A dark wood cubby hole exhibits a single painting titled Funny Man (1988-1990). The instance of an elderly man hopping around with pieces of undefinable stuff on both hands has a folkloric finish. The domesticity of the gallery setting where the emptiness and the art seem to be in a combat builds an eerie experience.

Courtesy David Zwirner

Courtesy David Zwirner

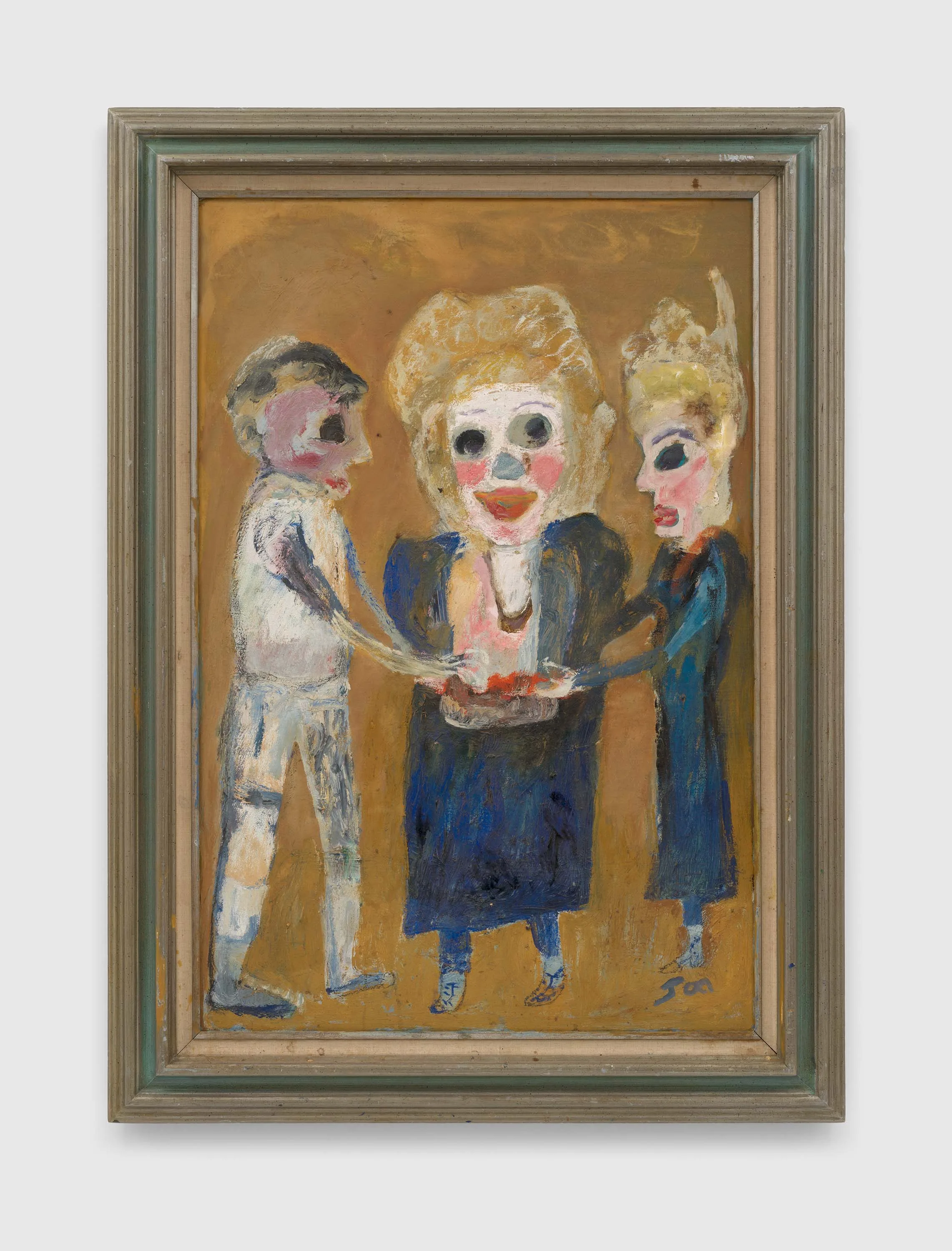

Fratino also delves into self-contemplation with his own portrait among flowers. Self with Pitcher and Candle (2017) has fiery dawn hues sliced by a queer purplish pink on Fratino’s lower body. Its romantically brutal painterly lexicon feels similar to Serl’s. Josh Smith’s untitled painting of palm trees from this year hangs adjacent to Serl’s also untitled painting with four figures on a bold red background. The trees and the humans in fact share a visual kin with the formers’ sapping branches echoing the latter’s raised arms. From the trees’ shine with their gleaming shades of red, pink, orange, and blue rises a haunting joy, not unlike the obscure sentiment shared between Serl’s characters, one of which lays over a green table and perhaps plays a flute with his hand and foot. Bradford’s Runaway Wife Shelters Her House (2022) contains the typical tension of a suburban dream house with an explosive calmness. The red roof is alarming but also like the sunset between the mountains. Serl’s The Preset with the Proposal (1962) has a similar static lunacy within its three figures’ vague exchange. Their bulging eyes hint that they might be hypnotized like an eager volunteer who jumps onto the stage in a magician’s show.

A delirious carnival and a haunting ritual, Serl’s world is at once everyone’s and no one’s. They are daydreams with firm attachment to reality while refusing logic’s mathematics for the visible world. The painter’s timeless effect perhaps stems from this peculiar handling of common human stabs with a warped emotional grandiosity, just like an actor stage.

Written by Osman Can Yerebakan