Writer Lydia Eliza Trail writes of the role of color and the socio-political implications of ‘gas’ in Coumba Samba’s Red Gas, on view at Arcadia Missa.

The combination of wall-mounted radiators and landlord-style blue carpet at Coumba Samba’s Red Gas, on show at Arcadia Missa until October 25th, is Unheimlich. The atmosphere is one of beige familiarity. Nine works from the series Radiators (2024) line the walls in baby blue, bright red, sand, light pink, and navy. The carpet, reminiscent of spaces ranging from school hallways to doctors waiting rooms, recalls impersonality. It has the off-putting spatial lure of a theatre set.

Over an email exchange, Samba explained to me how the mundane appearance of the radiators was purposeful: “I found some designy ones that screamed art object, but they wouldn’t have worked.” Focusing on the politics of design in all eight pieces, sourced from Gumtree and Ebay, Samba picked those that were most commonly for sale. She employs ephemera that one could quickly identify with the internet’s grainy, poorly cropped, poor image, “ a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances” (Hito Steyerl, 2009). Our visual association is not Duchamp’s Object D’art; it is simply the debasing “Column Radiator” listing on Gumtree: “Brand new column radiator 1600 x 544, with brackets and fixing. Purchased in Error”.

As you walk the upstairs room of Arcadia Missa, you’re provided with a bright red A6 pamphlet containing Mischa Lustin’s essay detailing the interwoven history of West Africa, Russia and the West. Sanctions on Russian gas exports have existed since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, but the West still buys through legislative loopholes (Lustin, 2024). At the same time, both superpowers scramble to mine untapped gas reserves in Western Africa. The legacy of colonialism in Africa, which Walter Rodney identified in his seminal text, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972), underlines the context of Russia’s anti-colonial (and anti-capitalist) stance in Africa. Through these layers of political negotiation, “the worst of capitalist reality” is exposed, and gas is sought.

It’s just gas, but it’s never just gas. Lustin writes, “The history of transnationalism is about flows, ideas, and influence, but also gas.” Samba emphasizes radiators’ objecthood because she wants us to focus on their functionality as vessels for gaseous currency. Samba engineers a “theatrical encounter” with the body turned monstrous; the radiator, our heat sources, and our domestic familiarity are perverted into weird diplomatic sentinels. The issue of colonial capitalism, which, to those in the West is often dismissed in the face of domestic issues, has become embodied. It is not via literal anthropomorphism but in what Michael Fried identified while discussing late modernism: the looming presence of objects (Art and Objecthood, 1967). Radiators appear as actors on a stage. Our heaters are the by-product of international relationships dating back decades – their objecthood dictated by dodgy politics and imperial logic.

Samba’s process applies memory into the built environment through color. Abstracting a singular image through color-picking is a method that generates a novel relationship between object – viewer – source. This strategy was used in World as a diagram, Work as a dance, a show held at Emalin Gallery in 2023. For Stripe Blinds (2023), the colors of the wooden slats are picked from a 2005 image of the artist’s sister. Hues of the images are sampled and abstracted, and a source-specific semiotic of colour is developed. “I see colour as a material for all works I create. It has its language with the viewer”, writes Samba. For a generation spent observing the world through a screen of imagery sifted for minutiae – what does it mean to give block color so much power?

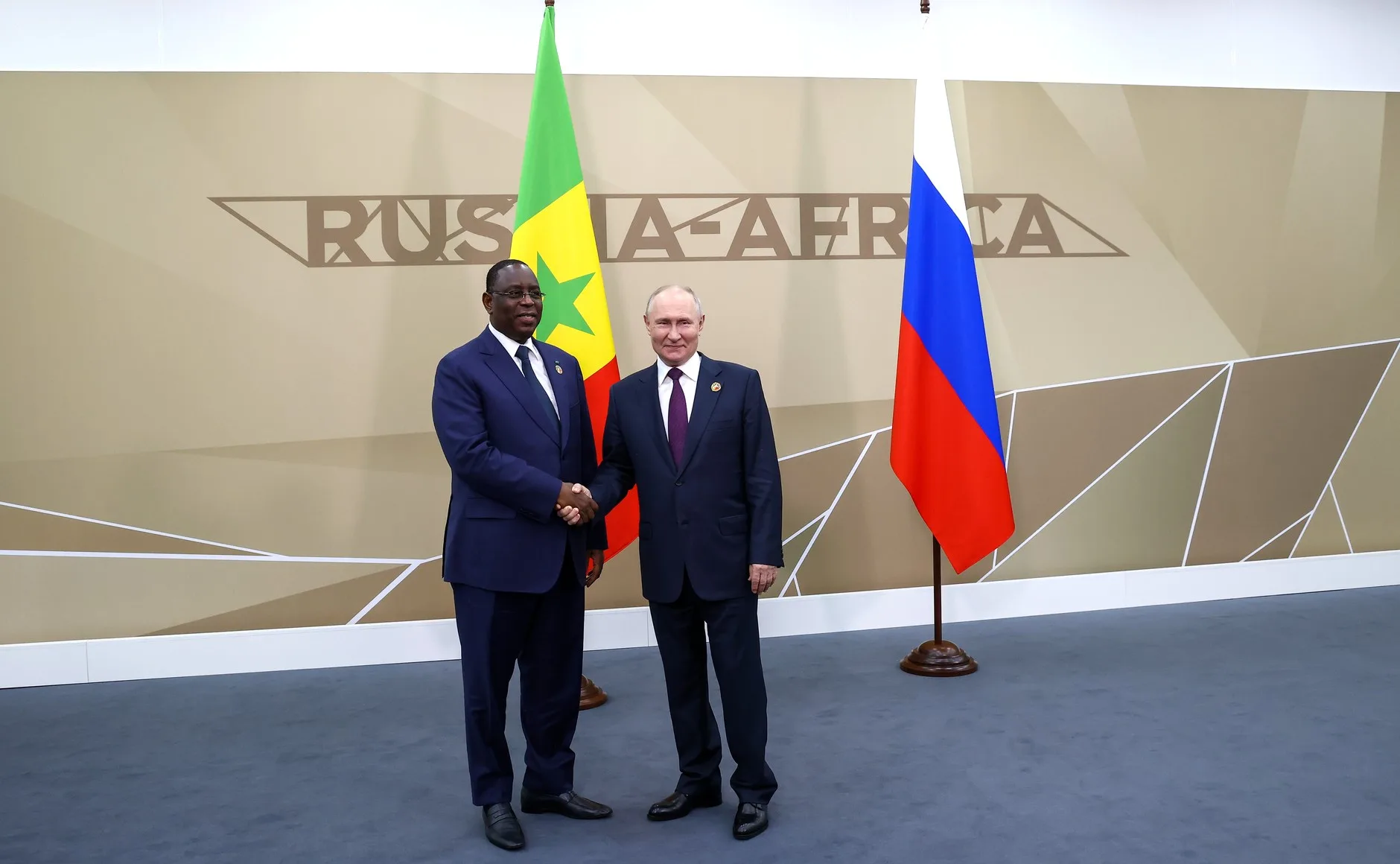

In Red Gas, the source material is again a singular image: Vladimir Putin and former president of Senegal Macky Sall (2023). Samba tells me that the blue carpet in the gallery matches that in the conference hall. Her choice of imagery in both World as a diagram, Work as dance, and Red Gas at Emalin is novel for its lack of aesthetic. One exists in an intensely private realm (a photo of the artist’s sister from a brief modelling stint) and the other a highly public one (president of Russia’s official website). Both avoid the middling sphere of “core” related imagery now rampant in the post-Tumblr vacuum of social media. Now that aesthetic categorisation dictates our consumption of online images; they are created and circulated with the pure purpose of referentiality. Once circulated, they are abstracted from their source to become an entangled footnote within capitalist self-identification or “cores”. In more unfortunate instances, this referential imagery has generated a genre of contemporary art entirely lost to a meaningless core-core. It is refreshing to see a reference that is not solely about references, as it allows for the essential political impetus of Samba’s work to stand on its own.

Samba’s ‘colour picking’ is not unlike the Instagram tool you use so that your text’s chromatics closely align with the image upon which it sits. An arrangement between text and image parallels the huge “Russia – Africa” text across the conference hall at the Russia-Africa Summit, colour-matching the corporate background. Block colours and modern art have a longstanding love affair. Russian constructivism, led by Rodchenko, influenced the modernists of the West. The Russian Avant-garde favoured minimalist art as a conduit for Russian Socialism; the object would be treated as a whole – “of no discernable style” (Constructivist Manifesto, 1920). These principles formed the visual language of anti-colonial propaganda produced by Russia during the Cold War. Nationalistic colour schemes were a vital part of the propaganda levied at Africa as part of forging a new Russian-African agreement that bypassed the West, as seen in images from the Wayland Rudd Archive.

The joy of color picking is that it obfuscates the relationship between source and image. Samba has previously spoken of her interest in the politics of national flags, describing her 2024 show This is Money at Drei Gallery as “a study of flags, of colonialism, of color.” Modern history saw block color emerging with socialism. As criticism progressed, color became more of a hindrance to form than a dynamic component; as stated in the press release, “minimalism and the history of modern art, in general, lends from the rest and reduces it to whiteness.” Samba asks how color can be transfigured into a vessel for memory, marrying the personal with the political through domestic objects and image-to-color abstractions. I ask Samba if Red Gas is resistant to classifications of minimalism: “Definitely not, but also yes.”

Words by Lydia Eliza Trail