Artworks come in many shapes and sizes but, for all the infinite variety of their contents, exhibition spaces have a tendency to look resolutely the same. White walls, high ceilings and intimidating front desk; no matter if you’re visiting a gallery in New York, London or any other city in the world, you’re pretty much guaranteed to encounter these tried-and-tested tropes.

The environment is so uniform as to have spawned a term all of its own: the white cube. But from the domination of this one-size-fits-all model has emerged a movement of resistance; one that takes a grassroots approach to exhibition-making. In recent years, artists and curators around the world have developed galleries in active, working venues, from supermarkets to factories to hairdressers—and even in their own fridge.

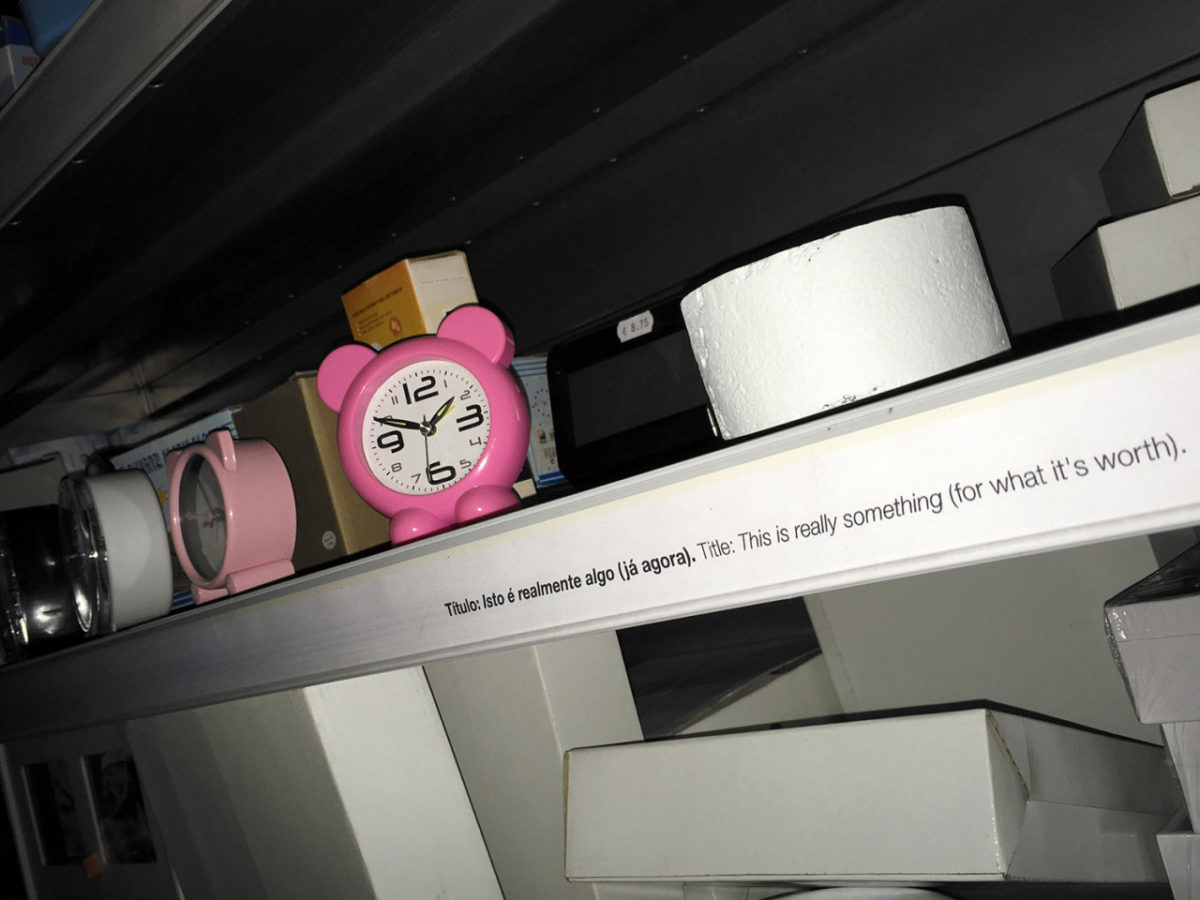

Bruno Zhu has run A Maior, a gallery in his parents’ 3000-metres-square home goods store in Portugal (“It’s a bit like Poundland,” he explains) for the last three years. “I started it as a response to a previous project that I initiated in 2015, when I invited my mum to curate a show of mine in a museum set-up. I was working with domestic interiors, and so to have my mum come and rearrange my works was very important. A mother is a curator of the household, in a way. I wanted to continue that conversation through opening the gallery. It came out of a whim, asking, why not?”

The same question was the driving force behind INOX, started by Danish artists Benedikte Bjerre and Asta Lynge last year in Copenhagen. It has so far hosted three group shows and one solo show by international artists, featuring sculpture, painting, sound works and film projections. It also happens to be located in Bjerre and Lynge’s fridge.

“People don’t overestimate what they’re going to see here,” Bjerre explains. “I like the combination of lightness with seriousness, of joking but meaning it for real. It gives a freedom that we wouldn’t have if we had rented a gallery space. It gives space for us to feel free, but also for the viewer to feel free—to not have to feel something in particular in the space. There’s not that pressure.”

“It gives a freedom that we wouldn’t have if we had rented a gallery space”

Bjerre and Lynge are part of a wider movement away from the traditional gallery. Beyond those confines, artists and curators are able to engage with different audiences and offer an alternative set of parameters for exhibitions. Formic is a gallery housed in an ant terrarium, ostensibly for the viewing pleasure of the ants. The information on its website explains that “It can be visited by the ants 24/7. Humans are invited to experience the documentation available on this site.”

Primer, a platform for artistic and organizational development, is located in the headquarters of water purification company Aquaporin. While Platform 1 Gallery and Metal Culture, in London and Liverpool respectively, are both set on station platforms. Bjerre and Lynge tell me that they have known others to start a gallery on their wristwatch, in their car and even on their nails—adding that they themselves have exhibited at a mini golf course, a ski resort and at the top of a parking lot. Lynge has an upcoming show slated to take place in a London brothel.

“We had both just moved back here from other places in Europe, and we had a wish to open some sort of exhibition space to show artists here in Denmark that we know from abroad. As in other places, housing is expensive and space is difficult in Copenhagen, so it makes sense to work with something that feels light, free, flexible and easy,” they explain. It is a similar story for Zhu with A Maior: “I had peers whose work I really liked, and I felt it could speak to this weird idea of exchange—not just financial but emotional and symbolic. The programme came together really fast; I was following a lot of artists who could contribute to the space.”

There are obvious advantages to running a gallery, quite literally, on a smaller scale. “There are not a lot of running costs; we don’t have to apply for funding; you have a lot of autonomy and it’s very independent,” Lynge says of INOX. “While you still have all the same issues and negotiations as if you run a big space. You still have to host the artists, and you have the same kind of discussions: what the lighting is, how we’re going to hang it, what materials are we going to use, how does this work with our previous planning, and of course the concept of the show. All of these things are the same, which is just really exciting that the format is so scaled down, so miniature, so handy.”

At A Maior the entire store is open for use by artists, meaning that customers are likely to encounter the exhibitions while out shopping. Similarly, the artists who exhibit in INOX must share space with the groceries housed in Bjerre and Lynge’s fridge. “The shop is turning eight years old this year, and we have our loyal customers who live around the corner; they are our primary audience. I am project manager of this space, and my aim is to tune into this audience. It interests me a lot to see how they react, to see how they consume and interact with the work,” Zhu says.

“We have our loyal customers who live around the corner; they are our primary audience. It interests me to see how they react”

“To have this gallery in a place that is more ordinary and quotidian, it’s a challenge for myself as a practising artist to be aware of what’s outside the bubble. Some of the customers, they don’t really care but they look at it. Sometimes they pick it up and bring it to the counter, and are annoyed when they can’t buy it,” he continues.

“It’s an exposition of the hierarchies of privilege here; I’m riding on my position of being the boss’ son. It’s not just about displacing the artwork from the white cube to a lived space, it’s about upsetting the order and it exposes a hierarchy of labour. I’m trying to create exhibitions, but I ask artists to be aware of the conditions of the store. What does it mean to be ethical in this case, or appropriate?”

- Kenneth Goldsmith, Hillary: The Hillary Clinton Emails, curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, exhibition view. Photo by Giorgio De Vecchi

These are some of the concerns raised by Milan-based curatorial duo Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, who curated an exhibition of Jonas Mekas’s late films in a Burger King in 2015, and this year staged an exhibition in collaboration with Kenneth Goldsmith titled Hillary: The Hillary Clinton Emails in a branch of Despar supermarket, both in Venice. For the Clinton exhibition (on view until 24 November) almost 60,000 pages of her now-infamous emails have been printed out for perusal. “We tried to propose the project to museums in the US and Mexico, but everyone refused,” Urbano Ragazzi recalls. “So we decided to present the project at the Venice Biennale, and started the process of searching for our location.”

After rejecting a number of classical palazzos, they stumbled across the supermarket, which was formerly a university building and before that a cinema. “We really wanted to deal with reality and daily life. It’s related with the contents of our project; choosing a non-traditional space was really linked to the Clinton emails. Almost everybody thinks about these emails as a very mysterious subject, containing secrets, so putting them in a public, daily life space, allows us to claim the opposite.”

Unlike Zhu, Bjerre and Lynge, Urbano Ragazzi must collaborate with external companies to see through their exhibitions, often relying on permission from corporations. “Curating this way becomes a more complex job or task. You are talking with the art system, with a general audience who are living their daily life, and also you have to enter into a relationship with a company. Curating becomes closer to a social role,” they reflect.

“It’s about creating a temporary community, and putting together people who were not interested in meeting in the first place. This concept is really related to queerness. You can’t decide on the identity of Despar: it was a theatre, a university and a supermarket, so its identity is always put into question. I consider our curating activity has a lot to do with building a queer space where everyone can question their own activity and identity.”

- DKUK. Photo by Jim Stephenson

This mingling of people from beyond the art world bubble can help to loosen preconceptions and transcend cultural stereotypes. “I’d say about seventy per cent of our audience don’t usually go to galleries,” Daniel Kelly, founder of hair salon-cum-gallery DKUK in London’s Peckham, says. He started the business five years ago, but moved to their latest location this March. “The art is an integral part of the business; we see it as a fifty-fifty split. It’s not just like a coffee shop with a bit of art in it.”

Kelly trained as a hairdresser when he was seventeen years old, before leaving the industry to study at Camberwell College of Arts in 2004. “People say that they find it very relaxing, which is specific to our context as a hairdresser. We have a captive audience, and it’s quite unique to spend that duration of time with a stranger—taxis are probably the only other place.”

“How do you produce something artistic under capitalism? Spaces like these can initially sound super silly, but they’re so visceral”

There is a long tradition of presenting art in surprising spaces. The gallerist Gavin Brown famously staged early exhibitions in diverse locations such as his apartment on the Upper West Side, an office cubicle in midtown Manhattan, an abandoned building in TriBeCa and a room at the Chelsea Hotel. In 1974, the curator Harald Szeemann created a small exhibition about his grandfather, who was a hairdresser, in his apartment in Bern. And for a time during the 1980s, Hans Ulrich Obrist ran a gallery in his kitchen, which he had never cooked in anyway, inviting artists such as Fischli and Weiss to show work there. “The non-utility of my kitchen could be transformed into its utility for art,” he remembers in Ways of Curating (2015).

What sets the recent spate of galleries apart is their ingenious use of fully functioning spaces. Unlike Ulrich Obrist, Bjerre and Lynge continue to actively use their fridge and kitchen. Of course, there are numerous galleries to be found in houses or apartments—often belonging to wealthy collectors—but these carry with them their own set of inherent privileges. For generation rent, the thought of even hammering a nail into a wall can be enough to conjure nightmares of disastrous landlord negotiations.

Meanwhile, in the case of domestic exhibition spaces in former artist homes or studios—such as Gustave Moreau in Paris or John Soane in London—the artists are usually dead. “We’re still alive, and this is where we eat,” Bjerre and Lynge laugh. “Plus, everyone has a fridge, everyone knows this feeling of coming home, opening it, staring into it, it’s this mental pause,” Lynge adds. “For me, it’s an action that I do a lot, and it’s something that a lot of people can relate to.”

It is largely this relatability that has driven the success of these alternative gallery spaces, both in terms of drawing new audiences and bringing artists together. “I think contemporary art right now is so elastic and fluid in its forms. It’s great that in 2019 people don’t feel intimidated or alienated by the fact that this is not a white cube, and actually embrace it, to find a place for thoughts in their practice that doesn’t have a space in an institutional set up,” Zhu reflects. Kelly of DKUK adds, “Artists seem to really love having something to respond to. It’s more fun cooking if you’ve got a couple of ingredients to work with at the start.”

However, the financial challenges of making a living in the art world, with funding for the arts increasingly squeezed, cannot be overlooked. Artist-run spaces are undoubtedly a response to these conditions, seeking out spaces where they can regain control over their work. “I’m searching for places that are accessible. I want to work, so I find ways to work,” Bjerre says, simply.

“How do you produce something artistic under capitalism? Spaces like these can initially sound super silly, but they’re so visceral. I think they speak much louder than presenting artworks in art-devised spaces. They’re a thought, a reflection, even vomit,” Zhu concludes. “Ultimately, this is a symptom of something much bigger.”