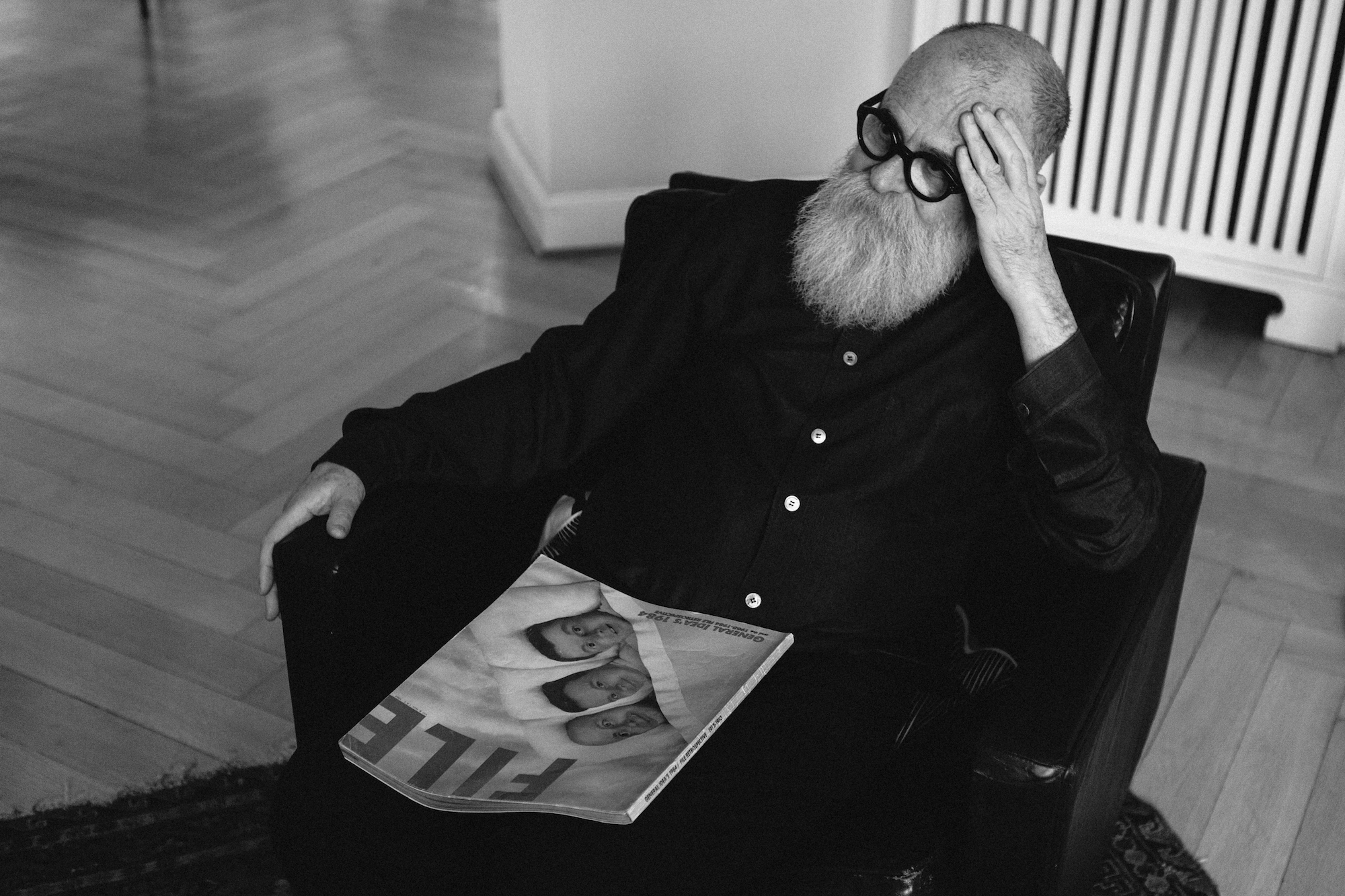

It’s early in the morning when I visit AA Bronson at his apartment just off Berlin’s busy Kurfürstendamm. He moved to the city with his husband—the architect and designer Mark Jan Krayenhoff van de Leur—and set up near Galerie Buchholz, which represented Bronson’s infamous art collective General Idea (GI) in the 1980s. Opening the large, ornate wooden door to his home, Bronson is unmistakable: impressive white beard, rounded glasses and kind eyes. I regularly see him from afar at Berlin’s art book fairs, carrying tote bags loaded with printed material.

In fact, Bronson is often referred to as the “Grandfather of Zines”, as Van de Leur points out, while I browse the artist books stacked neatly on the living room table. After participating in the early days of Canada’s radical underground publishing scene, Bronson lent his knowledge of publishing networks to GI’s mischievous foray into magazine making and later to New York’s Printed Matter bookstore, where he was director and subsequent founder of the New York and LA Art Book Fairs. Today he publishes regularly under his own imprint, Media Guru—he’s currently got three zines at the printer, he tells me. With my interest in publishing piqued, Bronson dashes past his cluttered white desk, covered in mail, to grab a stack of GI’s File magazine. Van de Leur brings us coffee—lots of it—and Bronson starts at the beginning.

Born Michael Tims in Vancouver in 1946, Bronson’s first move into independent publishing was in Winnipeg after a stint studying architecture. During the early sixties he founded a commune with a group of fellow dropouts; together they edited an underground newspaper in a distinctly un-hierarchical way. “We’d all get stoned, sit around on the floor and put it together—it was a quilting bee approach to publishing,” remembers Bronson. “Although the word ‘network’ didn’t really start being used until the seventies, that’s what this was: the underground papers were people outside mainstream society, all in touch with one other and sending each other work. It meant that in this little city in Canada we had contact with the international situationists.”

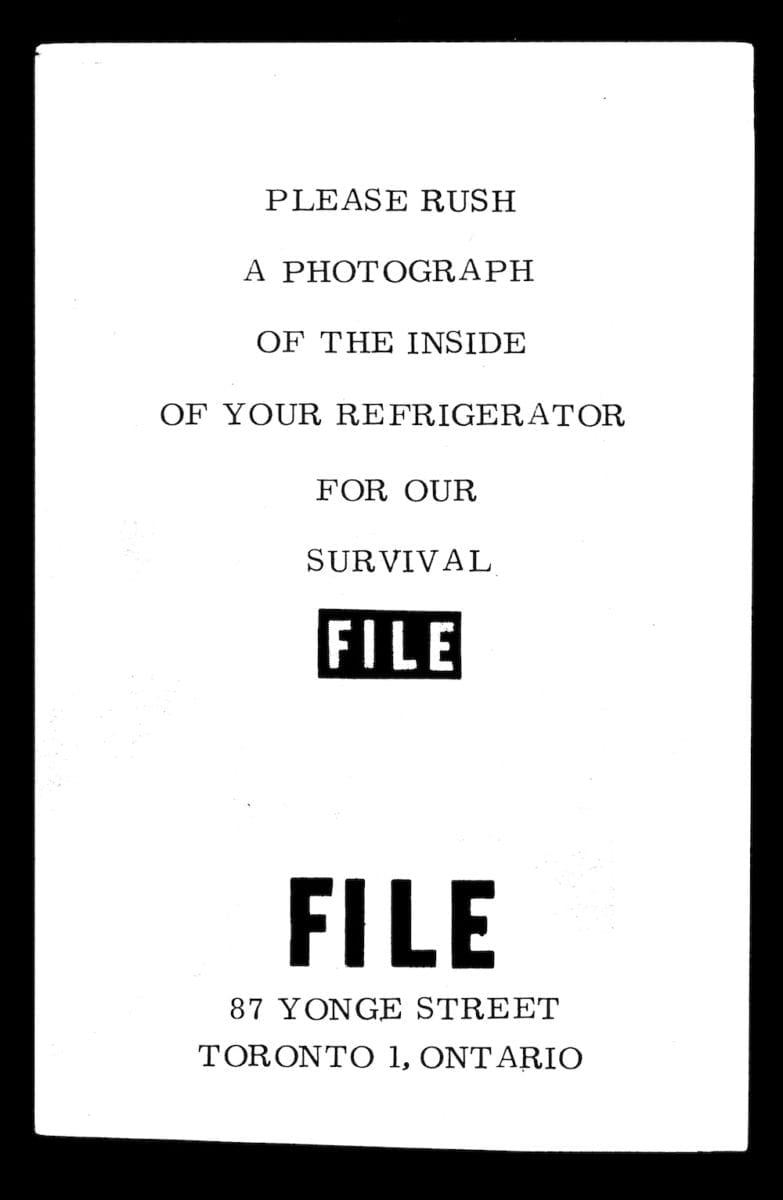

- General Idea, The Inside of Your Refrigerator, 1972

In 1968 Bronson moved to Toronto to participate in the Rochdale College experiment, a notorious commune that functioned as a student-run free school. He also began an apprenticeship at the experimental publisher Coach House Press, where he acquired skills for letterpress and book design. “In the meantime,” he explains, “General Idea started with all of us moving in together.”

In their home at 78 Gerrard Street, Bronson and fellow GI founders Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal sent chain-letter mail art projects out into the world and in 1972, they started publishing a magazine to document it all. According to Bronson, File wasn’t simply a magazine but an artwork by GI, integral to its project as a whole. They appropriated Life magazine’s red and white logo and reordering its name, a decision that spurred Time Inc to threaten to sue. “That was great publicity for us,” he chuckles. File was parody and performance, but perhaps most vitally, a Trojan horse. It flaunted its glossy, colourful cover on the newsstands, artfully disguising the cheap newsprint inside. “It was a parasitic thing,” says Bronson. “It could go into a certain system, into the distribution network of bookstores and so on. Because of that cover, it could go where smaller magazines from the time might just disappear.”

File took the form of mass media, but queered the content, parodying the stereotypes of gender with camp bravado. The “megazine”—as they often called it—reported on the group’s ever-evolving activities, beginning with mail art and then antics such as a “fake” beauty contest—the Miss General Idea Pageant. Bronson shows me the penultimate issue of the pageant, which the magazine had fervently promoted for years: the cover features an illustration of the pyjama’d trio together in a bed, eyes wide open to greet the morning. GI would set up “shops” in galleries to sell File along with other multiples, circumventing art world economics much like the Fluxus artists.

“The underground papers were people outside mainstream society, all in touch with one other and sending each other work”

Myth making was central to File. It satirized commercial conventions and the role of publicity, its cynicism coupled with a deep-felt optimism about the form’s untapped egalitarian possibilities. Especially during its early years publishing mail art, GI would use the magazine as a vessel, distributing its work and that of other unknown artists to a wider public. “The poor mailman would come in with this huge pile of submissions every morning,” remembers Bronson. “That’s how we’d start every day. By opening the mail.” These days, his routine involves sharing photos of his legs in floral pyjama bottoms with social media followers—another network of sorts.

Publishing File spurred new connections, generating new iterations and inspirations. Famously, its first subscribers were Joseph Beuys

and Andy Warhol; Bronson would hand-deliver the magazine to the latter. “When I gave Andy his first copy, he turned to Glenn O’Brien—the editor of Interview at the time—and said, ‘We’re going to put a colour cover on ours and leave it flat like File.’ They’d been folding it like a newspaper.” The following issue of Interview did just that. During this moment in the seventies, a new kind of publication rose from the gritty ink newspaper print of the underground: the independent magazine.

File was crucial in extending GI’s network across the ocean as well. For the collective’s first UK exhibition at Canada House on Trafalgar Square (“Who would want to go to an opening there?”), Bronson recalls only a few people turned up: Gilbert & George, Richard Hamilton, Derek Jarman and Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle—all avid File readers. “We went dancing afterwards in a little basement gay club. Gilbert & George started insisting we get up, twirling us around and throwing us into a bank of tables. That was our introduction to London. The magazine was partly what started that network.”

Meanwhile back in Toronto, the sacks hauled in by the mailman were growing incessantly, leaving mail art, underground papers, multiples and collaged ephemera spilling from every surface. Countless letters arrived from artists asking for advice on distribution. From all this chaos, the idea for Art Metropole emerged in 1974: GI’s library, archive and bookstore located in an abandoned space over a Greek restaurant downtown. Increasingly, it facilitated distribution for other artist’s publications. “I thought we were in an important moment in history,” Bronson determines. “There was this extremely lively and very egalitarian, horizontal movement through the art world and society. It’s quite unlike what it’s become today.”

“There was this extremely lively and very egalitarian, horizontal movement through the art world and society”

GI quickly discovered that museum shops were useless at selling File. Instead, in every mid-sized city in Northern America they looked for the one shop that had “a weird mixture of clothes, furniture and art books”, the precursors to the Dover Street Markets of today. There the publications would fly off the shelves. In New York during the seventies and eighties, that place was Fiorucci. “I think that one store got the word out about File just about as much as everything else combined. The contemporary art and culture magazine—things like Elephant—is very much a product of that history.”

In the eighties, the group stopped publishing File altogether: the critical distance from the art world weakened, as GI found itself increasingly enmeshed in its very centre. The group had also begun to focus their attention on the Aids crisis—its best-known work, Aids Project (1987-1994), appropriated Robert Indiana’s Love with the word “Aids”. In a media strategy similar to that of File, “Aids” postage stamps, posters and magazine covers distributed the image into the public—another “parasite” entering mainstream systems.

All the while Partz’s and Zontal’s own Aids diagnoses worsened, and in the early nineties the group relocated to Toronto for the healthcare system. Both Zontal and Partz died there in 1994. Bronson’s art production since has dealt intimately with the themes of trauma, loss, death and healing. In working through his grief, he trained as a professional healer, entwining this new identity with his solo artistic one.

Then, in 1998, after moving back to New York with Van de Leur, Bronson became a board member at Printed Matter, the notorious artist-run bookstore originally founded by Sol LeWitt, Lucy Lippard and a consortium of other critics and artists in the seventies. “After 9/11 happened, as the shop was near the site, business came to a complete halt,” he remembers. “Nothing was selling for months and months. The board asked if I was willing to be the director, to see if I could come up with a plan to try and save it.” Bronson, always the optimist, believed that the answer lay with the staff.

Printed Matter’s focus had been on rare artist books with hefty price tags, so their first decision was to take everything that was submitted—all the mini hand-scrawled zines. This egalitarian attitude stemmed very much from Art Metropole. Next, they started hosting small launches to activate the place, which “opened the door to the world of the zinesters”. When the store moved to the corner of 10th Avenue, Van de Leur designed the shop’s counters to look as if they were a bar, further emphasizing the idea of a gathering place.

“Meanwhile, there was this phenomenon going on where because of the Internet, bookstores were closing. Books were clearly dying. We tried to think if there was any way we could participate in improving the situation,” says Bronson. “Somebody came up with the idea of having a book fair.” The Dia Art Foundation lent Printed Matter a gallery to host the New York Art Book Fair—Bronson expected a few hundred people to turn up, but in the end there were 5,000. “We realized we had to do it every year. At the last one, 35,000 people came. I told them to stop doing music—just make it a little bit more boring!”

During April’s Gallery Weekend Berlin, an exhibition at Esther Schipper entitled Catch Me If You Can! juxtaposed works by GI with that of its surviving member, placing Bronson’s current artistic practice in conversation with the spirits of the collective. A pop-up bookstore featured catalogues, rare books, editions, and zines by both, as well as adding contemporary stock to those mischievous gallery “shops” once constructed by the trio.

Walking over to his desk, Bronson spills today’s newly-opened post across the table: queer zines, independent mags, hand-stapled photobooks and artist ephemera abound. “I get these in the mail every morning from the zinesters,” he says affectionately. “It seems to me that there are these art-intellectual clusters in zine publishing right now that are going to be important, but it’s still a little early to tell what they’re all about. There’s something going on though, another version of what happened, taking form as we speak.”

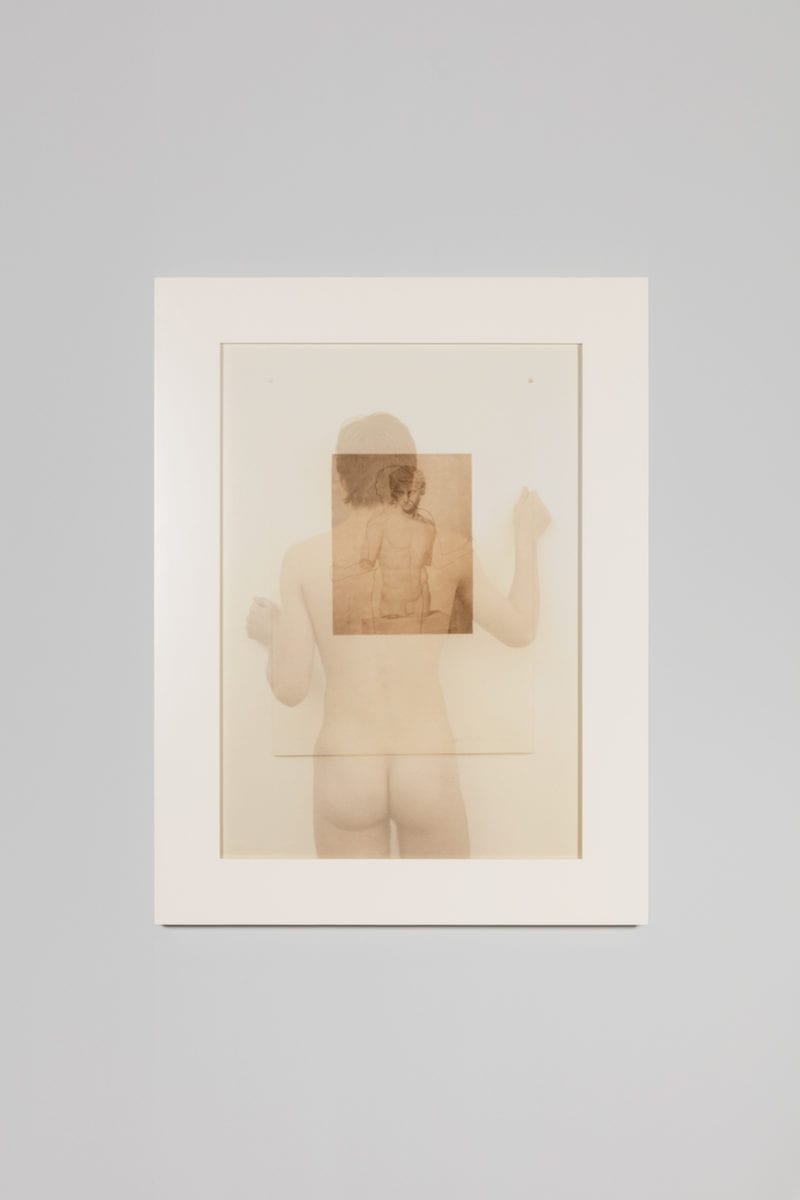

- General Idea, Paolini Project, 1978/2017

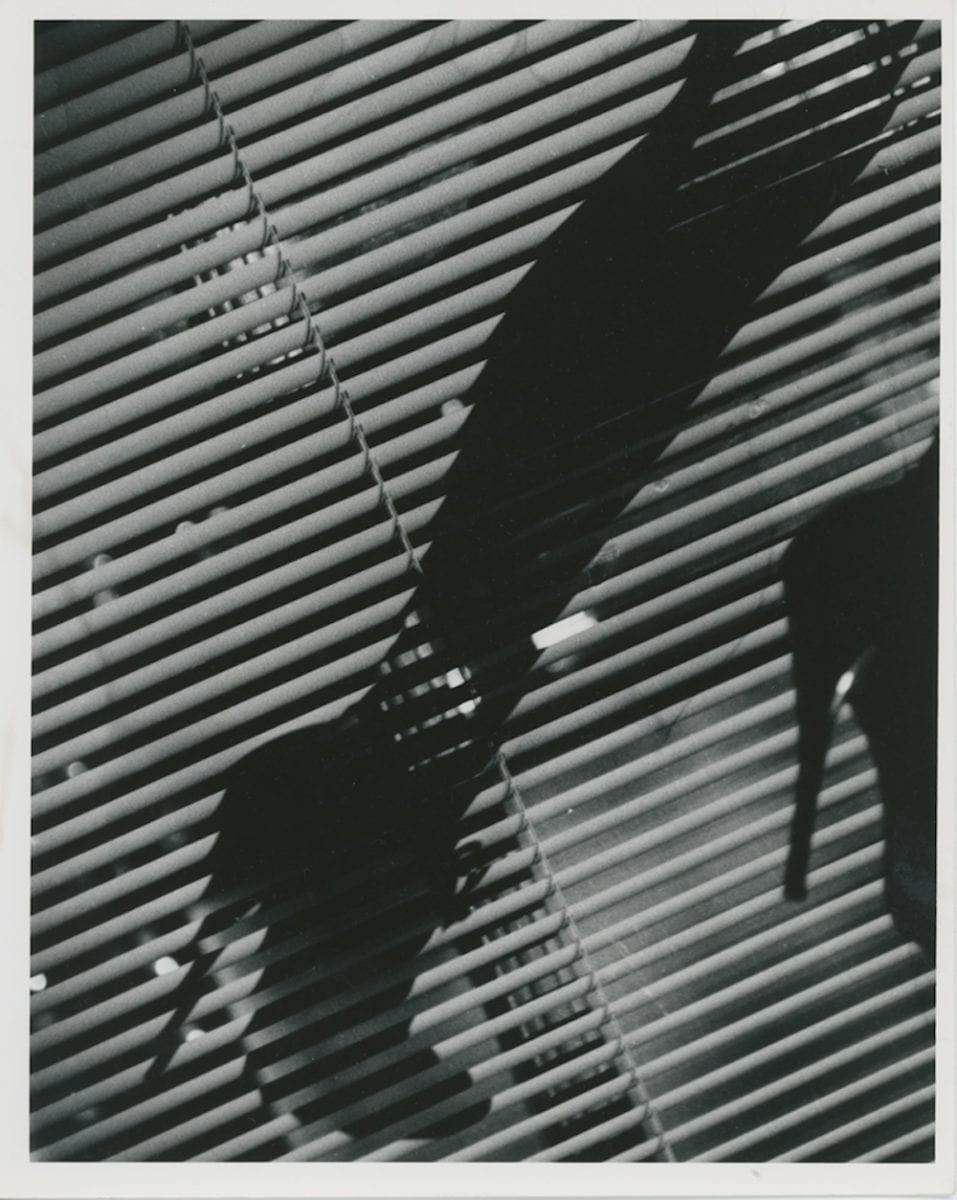

- Sandy Stagg and the Miss General Idea Shoe (Shadow), 1975

This feature originally appeared in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 5