It has been two years since Kettle’s Yard – the former home of curator and collector Jim Ede – started a major redevelopment. The Cambridge gallery is known for its astounding collection of modernist work of art, mostly amassed through Ede’s close friendships, and subsequently serving as inspiration for a variety of art world A-Listers (Nick Serota’s one of them) back when they were university students.

For seasoned visitors of Kettle’s Yard, it will be a relief to discover that the exceptional domestic compositions Ede created during his lifetime are preserved, along with the new interpretations provided when the original extension was completed in 1970. This rich tableau comprises paintings by Ben Nicholson and David Jones and sculptures by Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, to name a few, all set against painstakingly considered mounds of pebbles, shells, ornaments and ephemera.

Visitors are encouraged to sit down (on the chairs, but not the beds) in order to relax and appreciate these aesthetic configurations from every angle. Years ago, you could even grab a book and spend a few hours reading undisturbed. Now, the original collection is too frail to be handled, but prolonged visits are still encouraged. Once inside, it’s hard not to reimagine your life in this modern marvel, where a meagre beach stone can harmonize with work by some of the world’s greatest artists.

Now, with two new galleries, the harmony stretches even further afield. The inaugural exhibition, Actions. The Image of the World Can Be Different, brings together thirty-eight renowned and emerging artists (a few of which spill out of the white cubes into the grounds and house itself) whose work embodies probing questions about life, society and the relevance of art. Such questions were posed by artist Naum Gabo, an artist and friend of Ede’s, in a letter published in Horizon magazine.

In the foyer, Anna Brownsted sets the tone with Dilpomat (2016), where a continuous video documents a warped vinyl, playing a recording of JFK’s 1961 inaugural address. With the screen mounted unusually low, one has to stoop down to properly hear the audio, and the general discomfort felt while squatting inadvertently compounds the eerie unease you feel when you listen to the drunken distortion. In our Post-Trump existence, one can’t help but think that this liquified speech is still favourable to the violent ramblings of a narcissistic billionaire.

“This seems to instil optimism and hope, but it could just as easily signify a note of despair.”

In the adjacent gallery, political moments and notions of identity are explored. Mary Kelly’s Love Songs: Flashing Nipple Remix (2005) records the re-enactment of a protest at the Miss World Contest in 1971. The artist contemplates, “Doing it again, I was trying to ask—what’s passed on from one generation to the next?” Calling on our more immediate history, Issam Kourbaj uses copies of his surrendered, expired Syrian passports, calling attention to the huge restrictions of movement placed on the Syrian people and the devastation wrought on the country.

Two of the most arresting pieces on display strike a particular chord through their interplay. Caroline Walker presents one of a series of portraits called Home, where she has painted refugee women living in transient accommodation in London. Titled Joy, 11am, Hackney, it shows a woman washing her hands in the bathroom, in a moment of quiet solitude that doesn’t give away the trauma she has faced after being mistreated by her employer and dealing with frustrating legal aid.

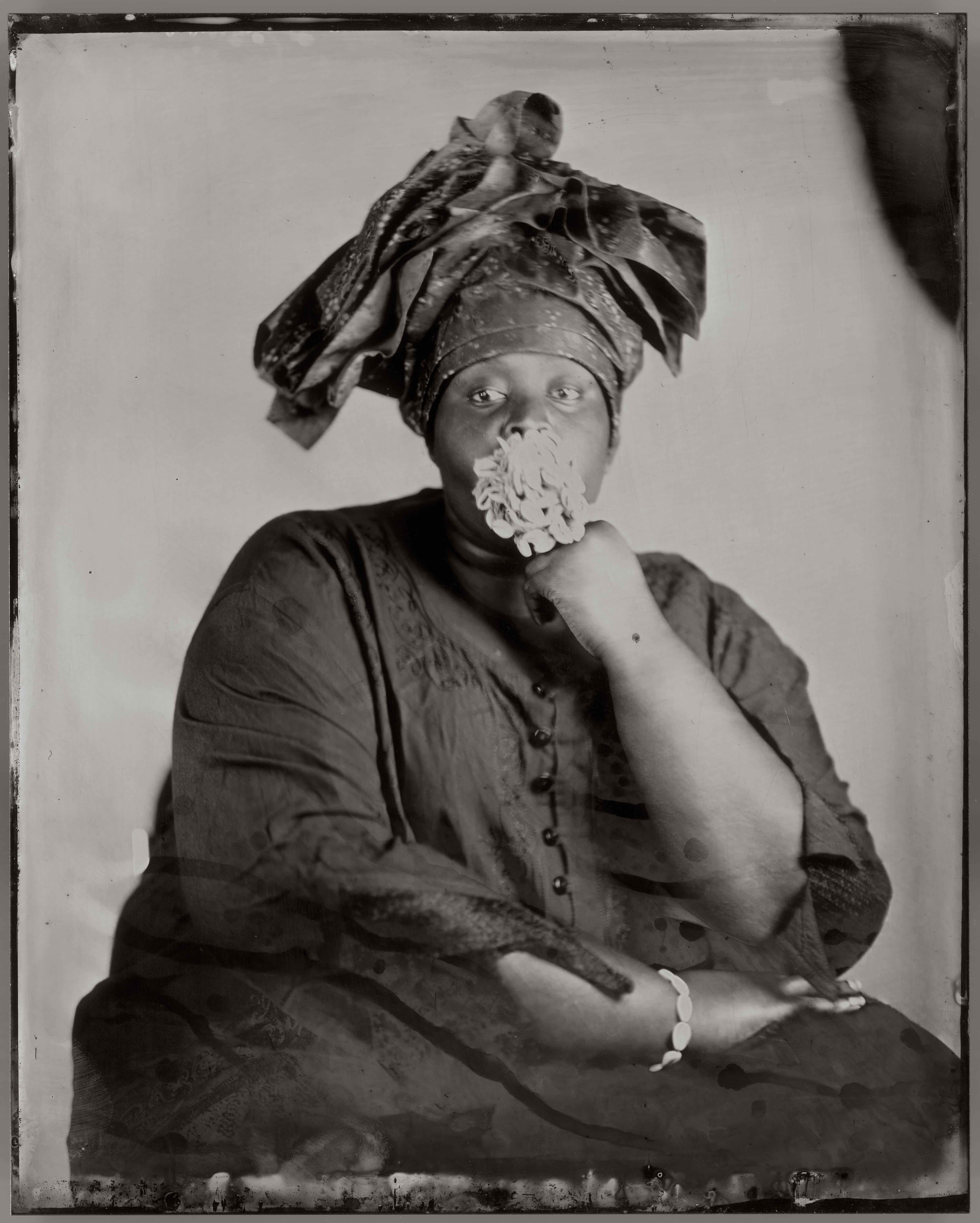

Nearby, Khadija Saye’s beautiful tintype self-portraits show her enacting a series of spiritual healing rituals drawn from her Gambian heritage. The elaborate photographic process casts ghostly folds and smears across the print and present dense, beautiful shadows, like something from an ancient, collective dream. Saye, who died in the Grenfell Tower fire, used herself as a subject as a way to “physically explore how trauma is embodied in the black experience.” The air of tragedy is impossible to ignore when viewing Saye’s work, and there is a melancholic and enraging thread drawn between her images and Walker’s painting; both subjects have suffered due to wider society’s negligence.

In the other gallery, big name, established artists such as Barbara Hepworth, Richard Long and Joseph Beuys represent ways of seeing that have since entered the art historical canon, but it is a newer work by Regina José Galindo that stands out. Her 2013 video Tierra films a new form of perilous land art, in some ways reminiscent of the bodily imprints left on the landscape by Ana Mendieta in her Silueta series. While Mendieta left marks in order to explore trauma, Galindo has the very land around her carved away by a bulldozer as she stands, naked, on an ever-diminishing patch of soil. The piece is a response to the acquittal of José Efraín Ríos Montt, the former Guatemalan president accused of murdering innocent citizens and disposing of them in a mass grave dug by a bulldozer. It is both harrowing and alarming to watch this woman shivering, as imminent danger surrounds her.

Such inferred violence represents the more extreme end of the political in this show, while others choose more opaque messaging. For example, Nathan Coley’s gigantic illuminated lettering spells out The Same For Everyone in the neighbouring church graveyard. On a day of abundant sunshine, this seems to instil optimism and hope, but it could just as easily signify a note of despair. Back inside the original house, several contemporary interventions have taken place, but it is Cornelia Parker’s introduction that is the most fitting. The intent of drawing delicate chalk marks on the windows in Helen Ede’s (Jim’s wife) bedroom is not overt, although the artist says the use of a material mined from the White Cliffs of Dover signifies home and identity. These veils of binary strokes create an odd sense of fabricated wintry weather or even the marks made by a prisoner, but mostly they subtly distort the outside world. These marks encourage you to sit and contemplate the everyday activities beyond the window and experience the mundanity of life in a new way.

In this beautiful home in Cambridge, I can imagine the worries of the world often seem far away, or even at odds with the greater trials many artists in this show attempt to unpick. But this exhibition does manage to reflect the ethos of Kettle’s Yard on a far larger scale. It encourages us to examine new connections and look closer both at our immediate environment and far beyond, and attempt to see everything––from hope to despair––with a fresh set of eyes.