On first entering a gallery, one might not expect to be met with an array of research papers, neatly filed and awaiting perusal, but this is the case at Delfina Foundation, where Kuwait-born, Amman-based artist Ala Younis has been invited to present her art-cum-research project around the forgotten histories of female Iraqi modernists. The notion of leafing through dense archive material might not be overly appealing for the average gallery visitor, so it is no surprise that most attendees bypass the crowded table in favour of an architectural model of a Baghdad gymnasium, designed by Le Corbusier and originally named after Saddam Hussein. Surrounding it are several out-of-scale female figures, none of whom seem immediately recognizable apart from Zaha Hadid, who is identified not only by her distinct sculptural dress but the knowledge that any exhibition mounted on the premise of spotlighting women who influenced Iraqi monument-building would be perverse not to include her.

Around the model, Younis has erected a timeline punctuated by two-dimensional copies of her figures, picked out and framed in red. Using archival images, statements and historical events, she maps an alternate history of often-overlooked women who shaped the architecture

of the country both literally and figuratively. These include Fahrelnissa Zeid, the artist and wife of the Iraqi ambassador in London, the Egyptian poet Iman Mersal, who visited Baghdad when it was under siege in 1993, and an unknown woman who attended the gymnasium’s new year concert in 1990.

“With every new regime, there was a new masterplan for Baghdad and its monuments. They were coming up and down and changing names depending on the president.”

This new work, commissioned in collaboration with Art Jameel in Dubai

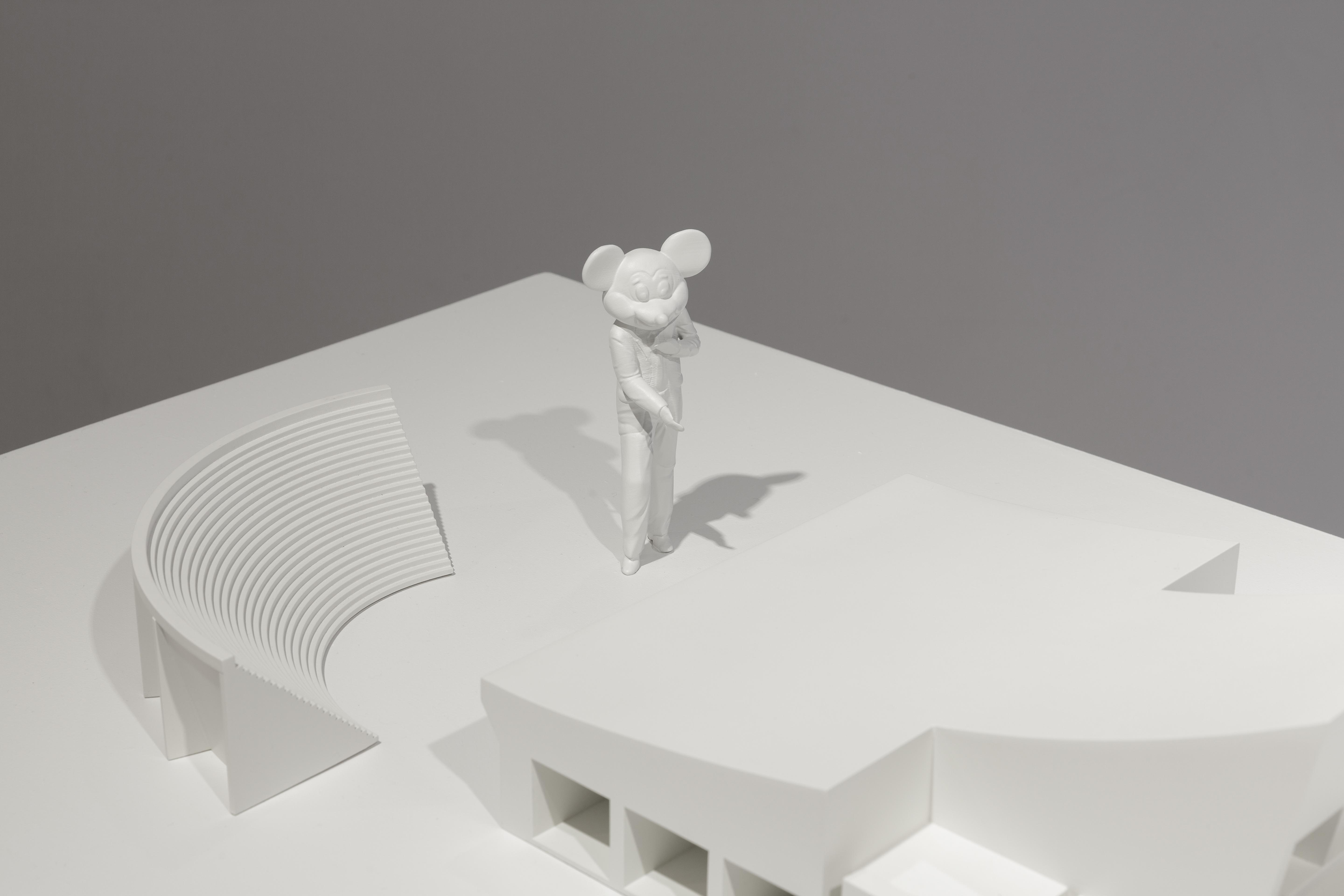

, weaves a web of parallel stories, where negligible details of everyday life spar with international events. Correspondence is pinned up next to archive shots of exhibitions and works of art, above an extremely detailed timeline that charts decades of conflict and regime changes. On the other side of the gallery the installation’s counterpart is revealed. This time the same architectural model is surrounded by male architects in a variety of energetic poses, while a malevolent Mickey Mouse looks on. This piece, titled Plan for Greater Baghdad, was created in 2015 and included in the Central Exhibition of the 56th Venice Biennale.

In the latter case Younis used the same archival display techniques, but this time the heroes’ model-portraits are presented in muted, charcoal tones, giving the piece a more sombre air. Younis explains that the original premise for this work was the discovery of a set of 35mm slides taken by Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji in 1982, including photographs of the gymnasium. She wanted to convey the huge shifts in the political climate, and the way this affected the city’s infrastructure and architecture, “with every new regime, there was a new master plan for Baghdad and its monuments. They were coming up and down and changing names depending on the president.”

The piece’s name is taken from an unrealized proposal by Frank Lloyd Wright, which laid out a vision for a new cultural complex and university on the city’s outskirts in the 1950s. It serves as a starting point for Younis’s excavations. The later addition, employing a subtle naming rehash: Plan (fem.) for Greater Baghdad, tells a parallel story of parallel stories––if you will––where Chadirji’s narrative reappears in reference to his wife Balkis Sharara, who carried his work in and out of Abu Ghraib while he was in prison, making three of his seminal books possible, and Ellen Jawdat, the Iraq-based, American architect who was hugely influential and served as inspiration and a mentor for Chadirji.

“The female version has more fragments and discontinuation,” says Younis, “because there are more hidden stories that you read a small amount about in a book… there might not be images.” Through her model-making she creates her own visual narrative, and shows a union between these personalities that might not always be entirely plausible, but they are drawn together by their common influence.

Younis has stated that her research will probably become a book and that these more sculptural works are only a taster of her in-depth study. It seems that a publication would be a more fitting expression, at least to give it proper due. The models are beautiful within themselves, and convey ideas of multi-layered stories anchored by one particular building, but the timelines are somewhat frustrating in their detail. It is clear that as a viewer you are only scratching the surface, and the appearance of one archive image, sketch or forgotten telegram serves only as a reminder that there are hundreds more to be discovered.

All images: Ala Younis, Plan for Feminist Greater Baghdad exhibition installation view, 2018. Photo Tim Bowditch. Courtesy Delfina Foundation and Art Jameel