It comes as no surprise that Alex Prager’s decision to become a photographer came after seeing a William Eggleston exhibition. She shares his obsession with hyper-saturated colour and manages to take shots that appear to exclusively inhabit the golden hour of the day. But while Eggleston sought to elevate the beauty of the everyday, Prager has no interest in reality. Her images are the result of meticulously calculated scene-setting, often using hundreds of extras, specialist props and exhaustive storyboarding to produce cinematic allusions that combine the romantic, anxious and surreal.

Prager’s new monograph collates ten years of image-making, including her more recent forays into film. It comprises of three parts—a rough chronology— that charts her ever-growing ambition, but also proves that her core vision of a leftfield, nostalgic American Dream has remained true. Part One examines Polyester (2007), The Big Valley (2008) and Week-End & The Long Weekend (2012), all of which embody the female-dominated, hyper-retro world that has become her calling card.

On first look, Prager’s images reference a twentieth-century nostalgia, befitting of the latter series of Mad Men, but on closer examination, everything is off-kilter. Her voracious use of bouffant wigs, vintage attire and thickly layered false eyelashes gives each model a theatrical air, and her use of extreme camera angles and an aversion to any form of eye-contact makes you feel as if you are stepping on the set of a newly conceived Stepford world.

“For Prager, the act of looking is much more important than studying the theory.”

Given the technical precision of her photographs, it seems almost impossible that Prager has had absolutely no professional training. She explains her abrupt career start in an interview with Nathalie Herschdorfer, ignited by the moment she saw Eggleston’s images at the J Paul Getty Museum: “I looked at the work obsessively. Within a few days, I bought everything I needed to become a professional photographer.” She goes on to explain a range of further references, from Diane Arbus to Helmut Newton, as well as a host of film directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Federico Fellini, and her childhood growing up in Los Angeles. It is worth noting that when she began experimenting with moving image, she was once again self-taught. For Prager, the act of looking is much more important than studying the theory.

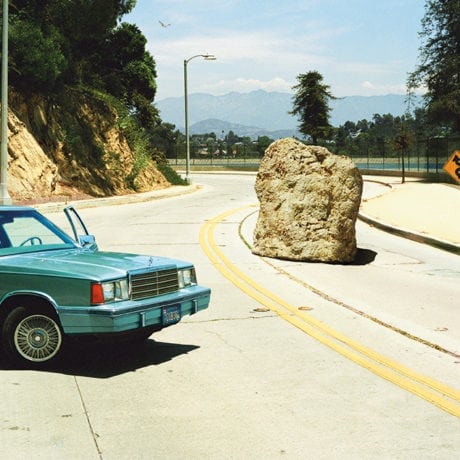

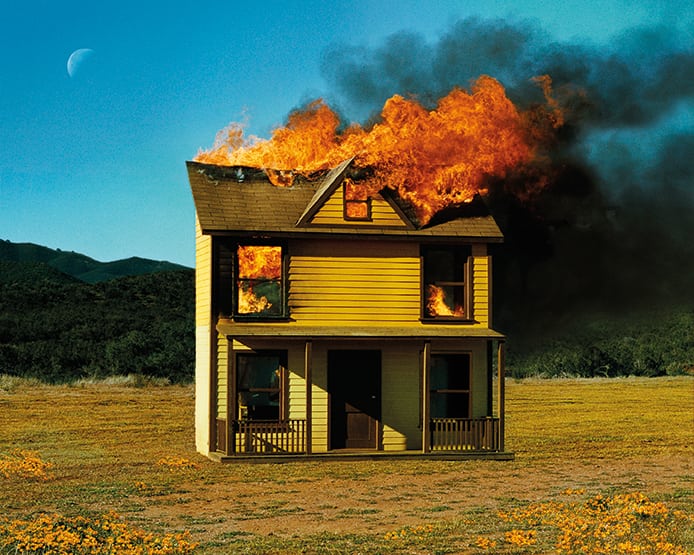

Looking is a primary concern in the opening pages of Part Two, where Compulsion (2012) features perilous, faintly absurd images of flaming buildings, car wrecks and drowning crowd, watched over by a series of separate images depicting closely cropped eyes. Each pupil takes in the dramatic scene unfolding on the facing page and is encased by either a ferocious arched brow or dramatic lashes. These vignettes are reminiscent of sixties thrillers or Man Ray’s infamous “Tears”, and the spectacular pairings seem at home on the printed page, where the tiniest nuance of each iris imbues the emotion of its counterpart in a spectacular fashion.

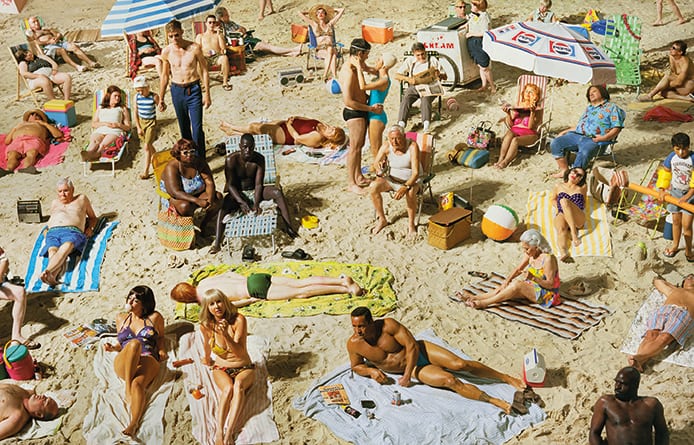

A shift in focus is evident in Prager’s incredible crowd scenes, for which she is perhaps best-known. Her rich tableaus are remarkable in the fact that, despite every character having a distinct and outlandish style, your eye is immediately drawn to key players who are almost invariably women. The eye travels with remarkable ease and always manages to rest on a particular figure that has been made exceptional through a particularly vivid light source, or a distinct, upturned pose. From this point, your gaze can travel outwards and get lost in a world of glamorous quirks and outlandish fashion— a veritable Where’s Wally for the modern age.

The latter half of this monograph is given over to Prager’s filmic works, which began as experimental forays after viewers continually asked what had happened to her characters immediately before and after the chosen single shot. An essay by Michael Mansfield situates her practice within the wider canon of experimental multimedia artists that emerged in California in the late sixties and seventies (Bruce Nauman and John Baldessari, for example). Mansfield describes her work as a “rich Hollywood concentrate” that is populated with “melodramatic renderings of tension, anxiety and suspense.” He offers a valuable investigation into Prager’s ability to distil emotions in a single image or an intense moving-image short.

“your gaze can travel outwards and get lost in a world of glamorous quirks and outlandish fashion— a veritable Where’s Wally for the modern age.”

While most video work is difficult to convey in a selection of printed stills, the fact that Prager shoots static and moving images in tandem negates the issue, to a point. The luscious anxiety of La Grande Sortie (2016) and Face in the Crowd (2013) are conveyed in beautifully articulated shots, but it would be criminal not to follow up by watching their moving counterparts (available online).

One final, unexpected addition to this book is a brief “Behind the Scenes” epilogue, featuring Prager running on set in jeans and trainers, brandishing a megaphone or a handheld camera, while models languish on a fabricated beach in a gigantic studio or a dancer perfects her pose. Considering BTS footage is now endemic in television, DVD extras Instagram feeds and live streams, it is surprisingly jarring to see the fourth wall of this impossibly glamorous and surreal world shattered. Fortunately, with only six shots in total, it is anything from an overload, which allows you to admire the incredible intensity of each set-up, without diluting the fantasy.

Alex Prager: Silver Lake Drive is published by Thames & Hudson on 14 June 2018 (£40.00)