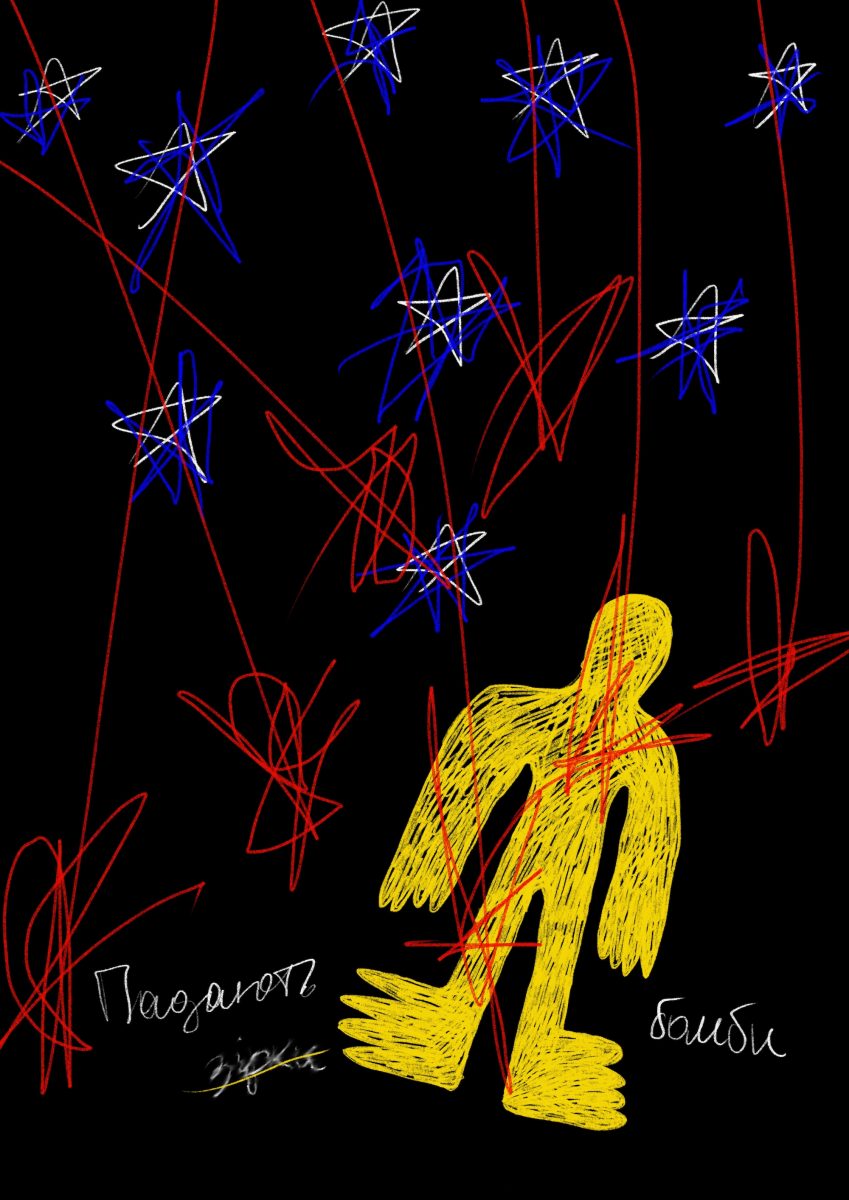

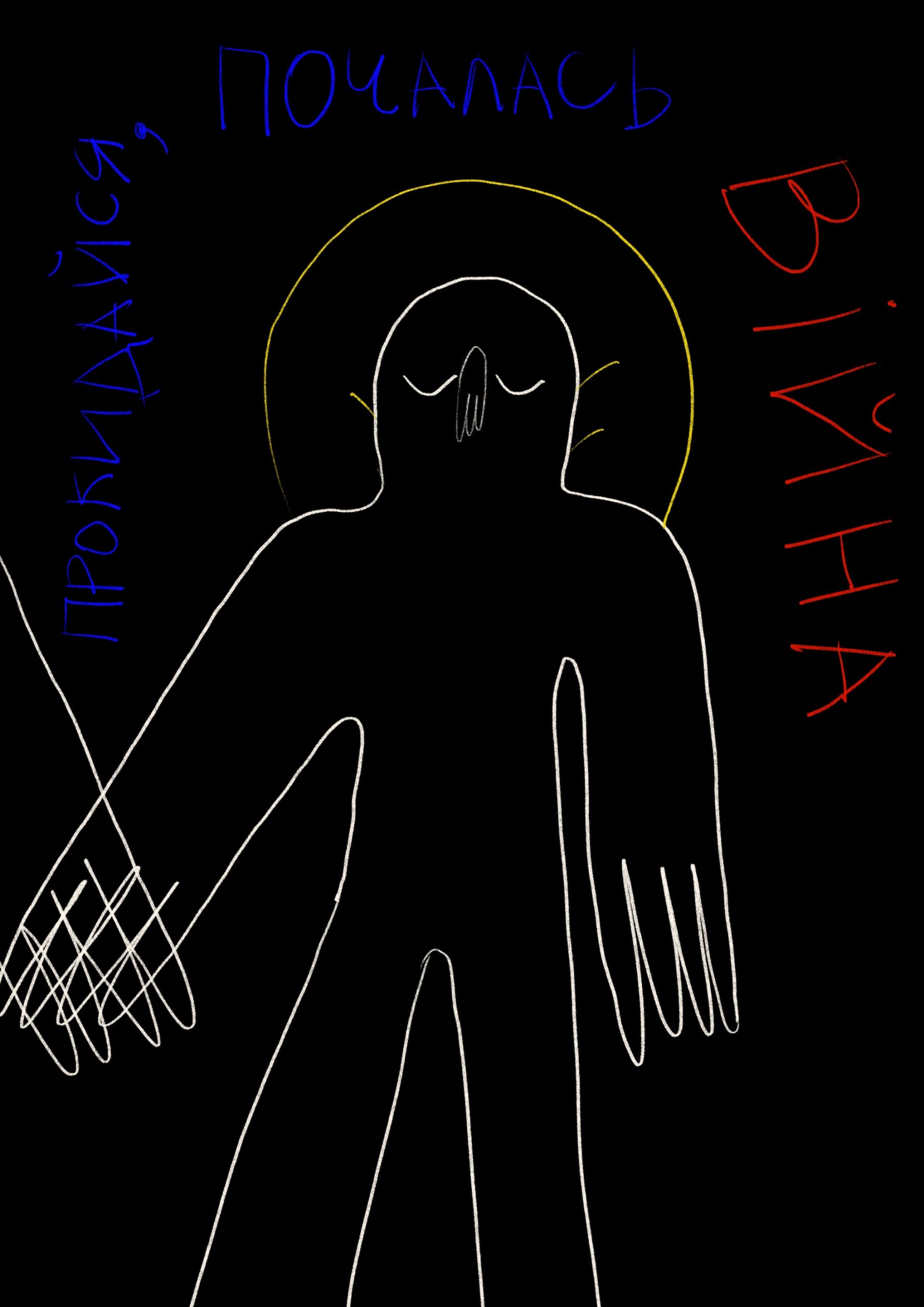

Anastasia Nekypila, Wake Up, the War Has Begun, 2022

“It’s a very strange and heavy feeling,” says Anastasia Nekypila of what it feels like to be a Ukrainian refugee in Poland. “It’s like you’re perpetually living in two different worlds at the same time. I could be walking along a quiet street in Europe, the sun is shining and the birds are singing,” she continues. “But that very second my country is being bombed and people are dying. My psyche still cannot accept these two realities.”

On 24 April 2022, during Orthodox Easter celebrations, Russia fired nine cruise missiles at Nekypila’s hometown of Kremenchuk in central Ukraine. “My dad was at work when the ceiling collapsed on him,” she remembers. “Miraculously he did not die.” On 12 May, Russia again fired 12 missiles at infrastructure facilities in Kremenchuk. “The rockets flew so low that my grandmother saw them.”

Since the start of Russia’s war on Ukraine, which actually began eight years ago when Russia seized the territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine and annexed Crimea, Nekypila has channeled the pain of her country’s displacement into her work. The resulting drawings, grouped in two distinct projects, are produced entirely on her iPad.

“Love and fear are not contradictions, and neither are hatred and bravery. Instead, they form the double helix of Ukrainian resistance”

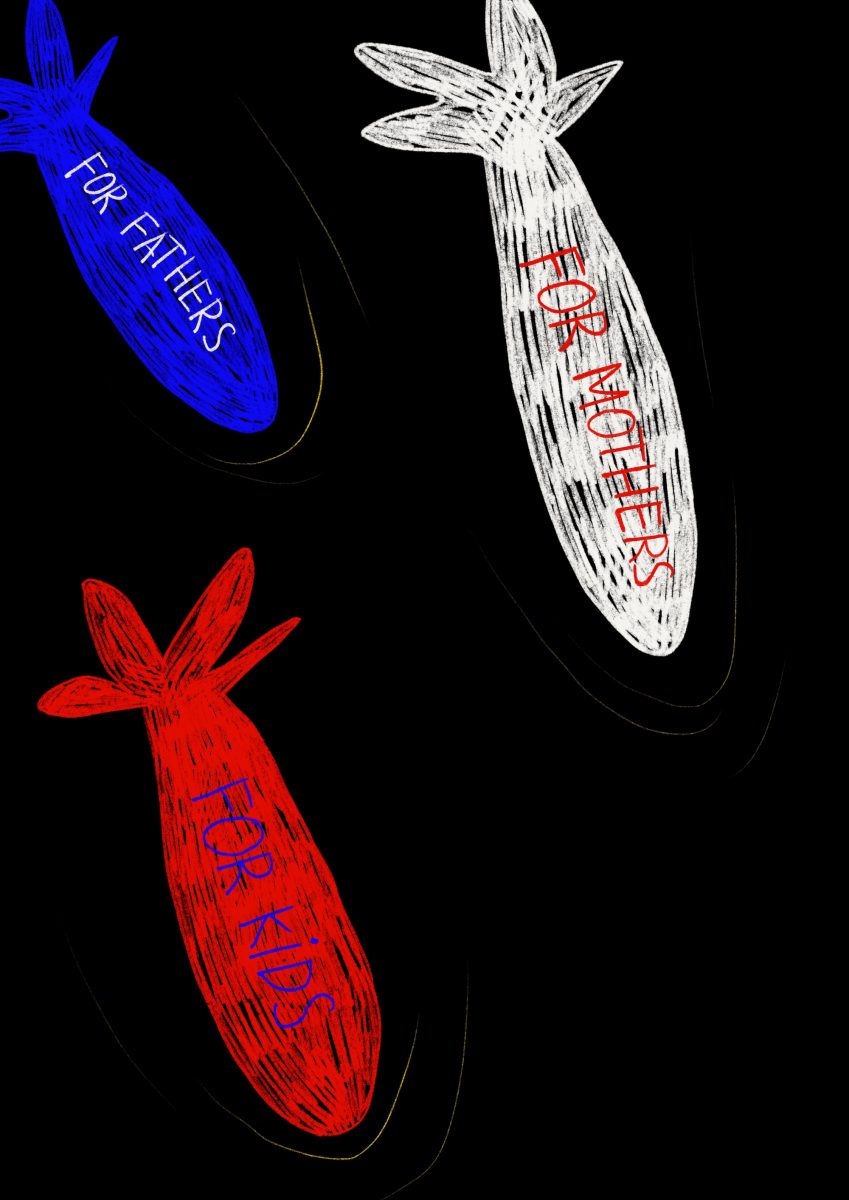

Wake Up, the War Has Begun reproduces images seen on the news, set against a black background, to show the suffering and loss experienced by Ukrainians. While some of these are direct calls-to-action, others are more allegorical. In one drawing, a Russian warplane is disguised as a spoonful of porridge, a nod to the way Russian propaganda lies to the world and its own citizens.

The title of the series, Wake Up, the War Has Begun, is taken from the actual words spoken by the artist’s aunt. Nekypila describes the first morning of shelling as the day “all colour and positive emotions abruptly disappeared from my life”. The inscriptions in the series are written in Ukrainian, as well as Russian and English. “The phrases in Russian are my personal attempts to understand the citizens of the aggressor country and talk to them, while naming the horror they inflict for what it is: war and genocide, not a rescue.”

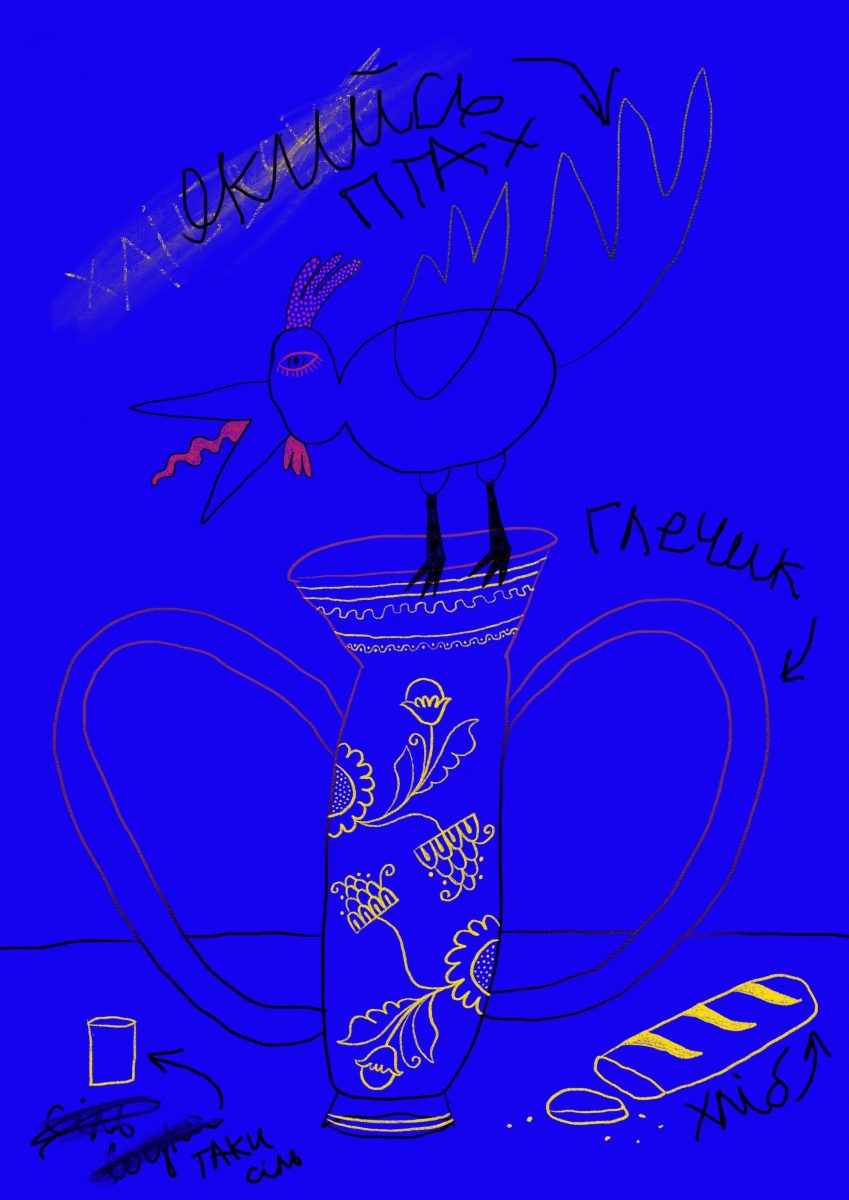

- Anastasia Nekypila, Ukrainian Naive Soul, 2022

By contrast, her series Ukrainian Naive Soul radiates with infinite love for her homeland through references to folk song, decorative arts and ancient customs. Its vivid colour palette recalls the beautiful folk art of Maria Prymachenko (1909-1997), who turned the most traumatic parts of Ukraine’s history, the horrors unleashed on her country by Stalin, into visionary paintings.

Nekypila’s simple line drawings of storks, sunflowers and cockerels pay tribute to self-trained painters: “I am inspired by unknown artists, those who paint their fences and garages, or turn old tyres into sculptures in their driveway.” What she means by “naive” is less to do with an aesthetic or one set of artists who exist “outside” traditional circles, and more a way of life. “We are creative as a nation. We are building our own free world, based on our own rules,” she argues.

“What war erases is a sense of security. If anything, it teaches you to rely on others. You learn to trust complete strangers”

“Naive” is a term of endearment and introspection for someone navigating their own identity. “The Ukrainian soul is without limits, free, courageous, unique and ready to do anything to protect itself,” she says. “For me, its the image of a brave child who has picked up a felt-tip pen for the first time and begun to draw. A child who cannot draw well but knows the meaning of the word ‘Ukraine’ and wants to express it.”

“Both projects,” she explains, “are about my feelings about Ukraine and myself as a Ukrainian. But they could be taken as complete opposites.” Dualities abound across these works. Nekypila reflects upon what it means to love your homeland and the terror experienced in the face of losing the place that you have known all your life. We learn that love and fear are not contradictions, and neither are hatred and bravery. Instead, they form the double helix of Ukrainian resistance.

Does war break our capacity for love? Nekypila remains optimistic: “What it erases is a sense of security. If anything, it teaches you to rely on others. You learn to trust complete strangers who cross your path. It’s these moments between strangers that bolster you up.”

Liza Premiyak is a London-based writer and photo editor at Getty Images, and a former editor at The Calvert Journal

Up, the War Has Begun by Anastasia Nekypila

forms part of the group show (un)WELCOME at Krakow Photomonth Festival, Poland, until 26 June 2022