The New York-based artist reaches new heights in his current exhibition, which includes a circus performance and an architectural structure.

Derek Fordjour, two years ago, had a unicycle sitting at his Bronx studio. He was then dabbling with different concepts for his recently-opened solo exhibition, Score, at the New Yorker gallery Petzel. “I knew a single object could be a mediator for larger ideas,” he remembers today for Elephant. “Reconciling” with the jubilant vehicle’s day-to-day presence at his sight prompted the show’s similarly festive themes of circus and celebration—so much that visitors can occasionally encounter a unicyclist roaming the large-scale paintings of Black figures in leisurely endeavours and sculptures of wheels, legs, or amphitheatre spectators. Passing beyond the veneer of joy, one may notice the cracks and even the punctures over the paintings’ surfaces, too.

Preparing for a highly-anticipated show that would follow his institutional solos at the Pond Society in Shanghai and Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis had imposed pressure on Fordjour, such as the decision to eventually give up learning to ride a unicycle. The ambition, however, shines through the show via other myriad lanes, perhaps most strikingly with Arena, a built-in circus inside the gallery with daily performances choreographed by Sidra Bell.

Greeted by a ringmaster, the audience perches over circular breachers and watches five performers dance to a range of compositions, from live banjo and violin to Donald Glover’s rap anthem This Is America. Throughout a thirty-minute run, an insistent elation native to any circus spectacle suddenly changes to a downfall, followed by mournful hymns. Dancers embrace and challenge one another in an orchestrated solidarity, and later, they lift and carry one of them; occasionally, they imitate running, albeit without a destination. The audience’s role along the way fluctuates between a spectator and a witness, overcast with the changing lights inside the oval-shaped tent: a passive participation crescendos with the dancers’ invitation to cheer and immediately crashes down with a performer’s collapse onto the dusty floor. “I wanted to bear all the layers that would make the dancers accessible depending on the viewer’s perspective,” says Fordjour. “When an implication of a violent act occurs amidst the cheering, it is a disruption, just like the racist structures and institutions in the society.”

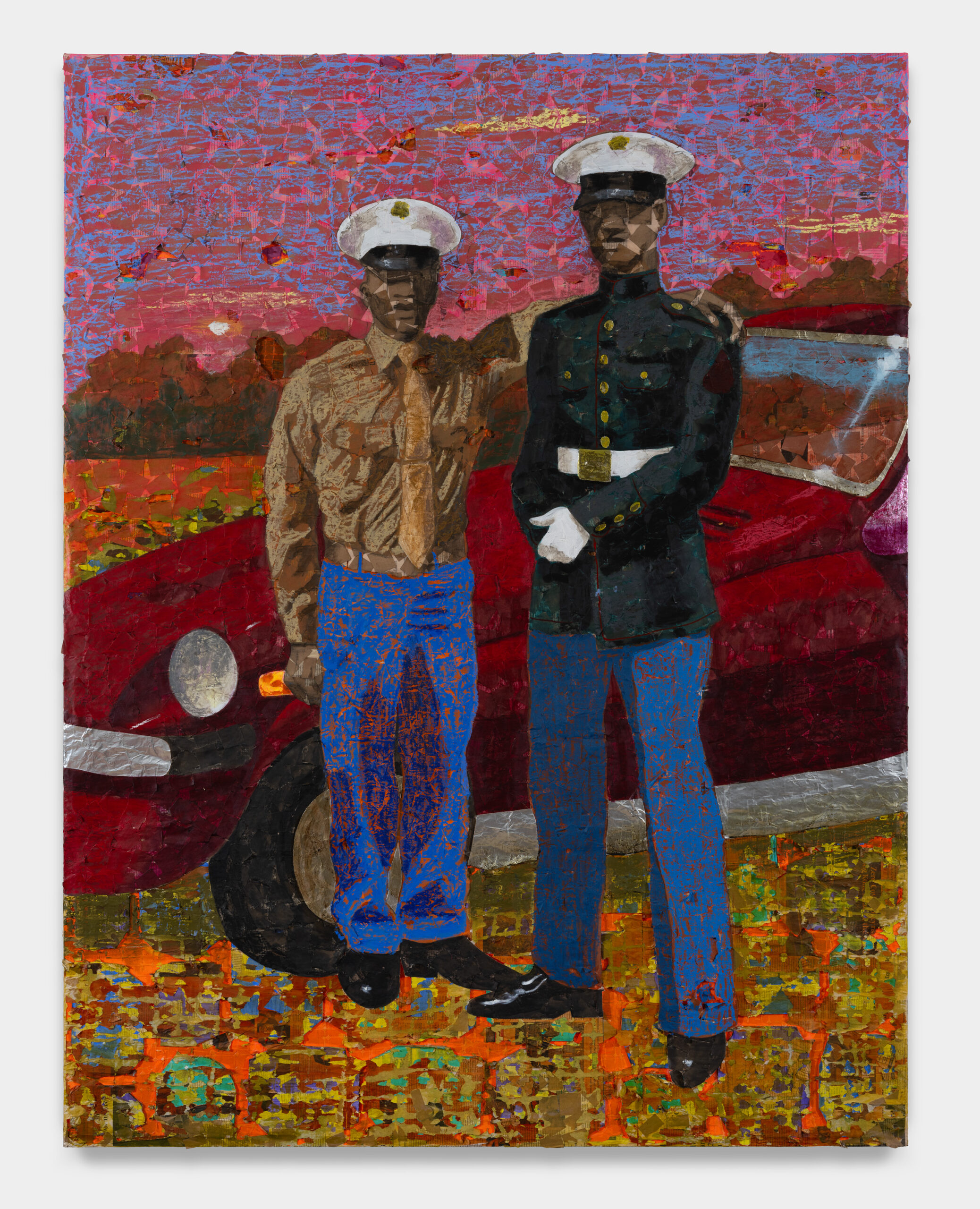

The tour-de-force performance is a reflection of the forty-nine-year-old artist “negotiating with the reality and absurdity of living in a Black body,” and there could hardly be a more suitable blank canvas than a circus setting to explore such contradictions between hard facts and senseless violence. Not unlike structured theatricality and flamboyant acrobatics veiling the ankles getting sprained and animals being tortured, Fordjour paints systematic racial targeting and oppression behind his upbeat colour palette and energetic gestures of his subjects.

In Pantheon of Truncated Ambition (2023), thirteen young Black boys and girls pose on a parade float. A female figure leans atop a circus pedestal while the other two hold onto stripper poles. Boys don attire suited to either rappers or athletes, using a basketball or jukebox as props. The confident ways in which they carry their bodies remain difficult to grasp on their facial expressions: Fordjour’s handling of the subjects’ visages with cardboard cutouts and newspaper yields emotionally detached and optically abstracted results. A closer look at one of the faces makes the words “can no longer” legible on a worn-out newspaper amidst washes of glitter and oil pastel. “Absurdity is a notion I genuinely feel about the Black experience—it is like a tired circus that keeps coming around,” expresses the Memphis-born artist. “There is tragedy in there,” he adds about his carnival, where “bright lights and pleasant energy create a bizarre reality of loss.” The police murders of Black Americans, as well as the centuries-long trajectory of racism, rest deep in his work “because heinous things happen in plain sight even in safe places.”

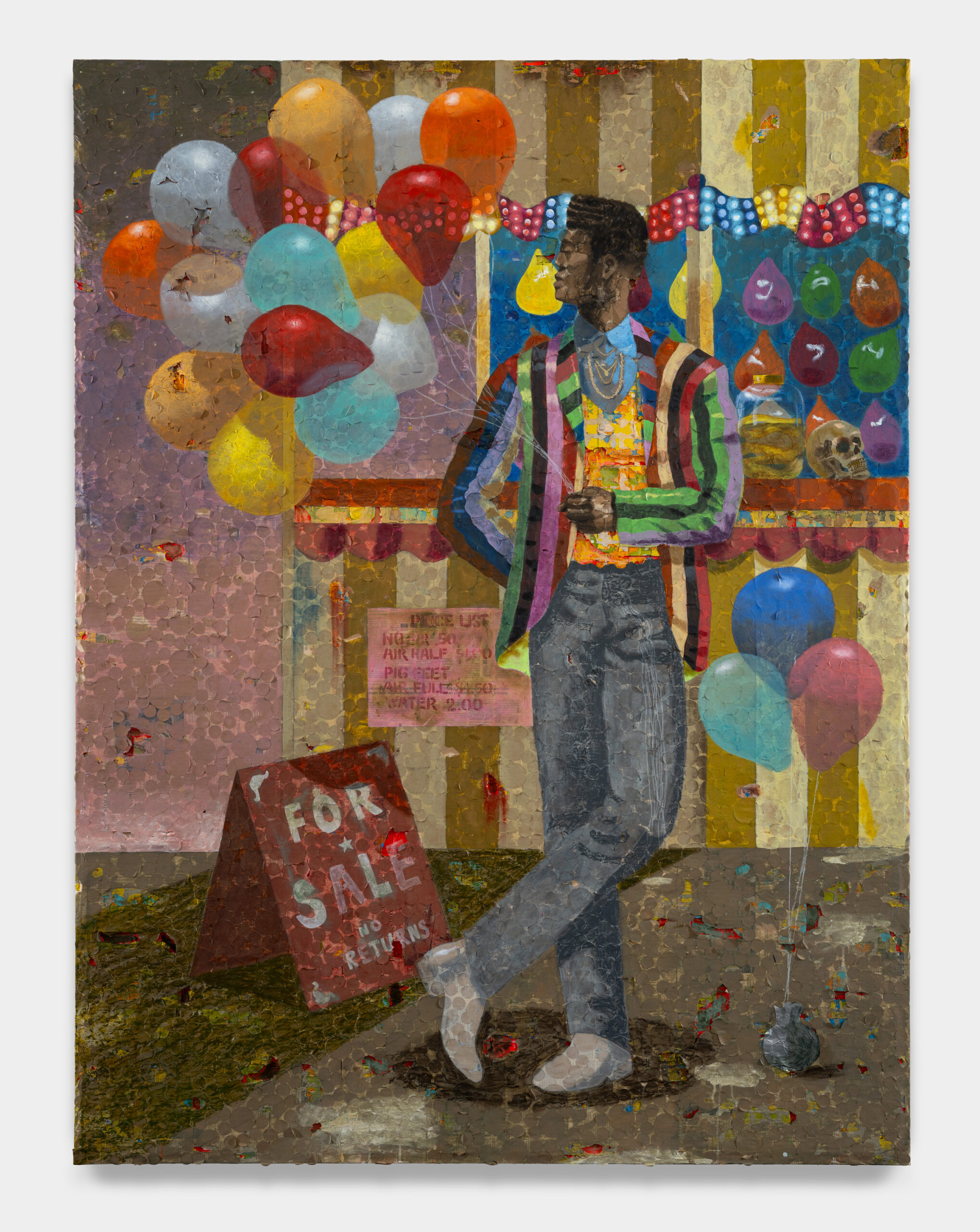

CONfidence MAN (2023) shows a young man—inspired by the artist in his early thirties—dressed as a circus worker in a dapper suit with an extremely colourful blazer. Bouquets of balloons surrounding him echo his sartorial colour palette. A tongue-in-cheek sign reads “For Sale No Returns” about the balloons that he intends to bargain for. “Humor is one of the ways marginalized groups negotiate trauma with,” thinks Fordjour, “this is, however, not to be taken with face value because it is a strategy, a device.” He believes in a role as an artist “to compel the viewer to invest time and energy into ‘looking’,” which prompts the artist to “never forget the form in a painting.”

The sensibility in Fordjour’s approach to his canvas partially stems from his considerably late ascendance to art stardom. He received a BA from Morehouse College in Atlanta in 2001, followed by receiving a Master’s degree in art education from Harvard University the following year. Wide recognition arrived around 2015, a year before he graduated from Hunter College with an MFA.

During his roughly two-decade search for a defined artistic path, he experimented with portraiture. “Being trained as a classical easel painter,” he remembers, “felt stifling,” but he found solace in drawing. He was attracted to the tactility of charcoal and the immediacy of “getting dirty, just like the ways the dancers’ white suits get smeared with dust in the performance.” He challenges a perfect presentation of painting with “a perpendicular stretch canvas, a certain tension, and perfectly prepared ground” through a balanced imperfection. Holes, tears, and blemishes span Fordjour’s rough surfaces. “Easter eggs,” he calls the traits that emerge from his paintings upon closer inspection, “elements of discovery waiting to be excavated.” Personal introspection and “lots of therapy” brought him to “peace with fractures and being comfortable with brokenness.”

Whether building a career or visiting an exhibition, a journey unfolds with its rewards and surprises. Going upwards through a narrow staircase in Fordjour’s show leads to a dim corridor of sculptures inside vitrines. A cyclist, an equestrian, or a trampolinist appears in full form or only with their limbs riding a wheel or clutching a ring. Ambition, luck, and gain are promised, although the outcomes are left unresolved. “There is desperation in aspiring stability out of struggle,” says the artist. The vulnerability of being on stage or on a field is oftentimes parallel with scrutiny. “For Black and Brown communities, struggling out loud in the arena has an insidious nature.” The push-and-pull between triumph and defeat continues through the maze-like hallway, where two moving sculptures show numerous miniature cyclists and horse riders on endlessly rotating on treadmills. The vicious entrapment of the figures dressed in ambition embodies “questions about social progress, as well as an individual one, and how we measure achievement.” Down another staircase, the theatrical setting reaches a finale with two actors performing the roles of secret puppeteers in charge of operating the kinetic sculptures. Indifferent to the visitors’ gazes, they converse and engage with their tasks.

For several years, Fordjour had indeed kept the human figure out of his paintings “because it had become a standard for prescriptive emotion.” He today uses marks, disrepair, and tears as a way to convey process and texture for his poised figures: “I want the works to have potential even if a viewer doesn’t understand a narrative or recognize a symbol because the sheer physicality of the work can hold an emotional bond.”

Words by Osman Can Yerebakan. Images courtesy the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York