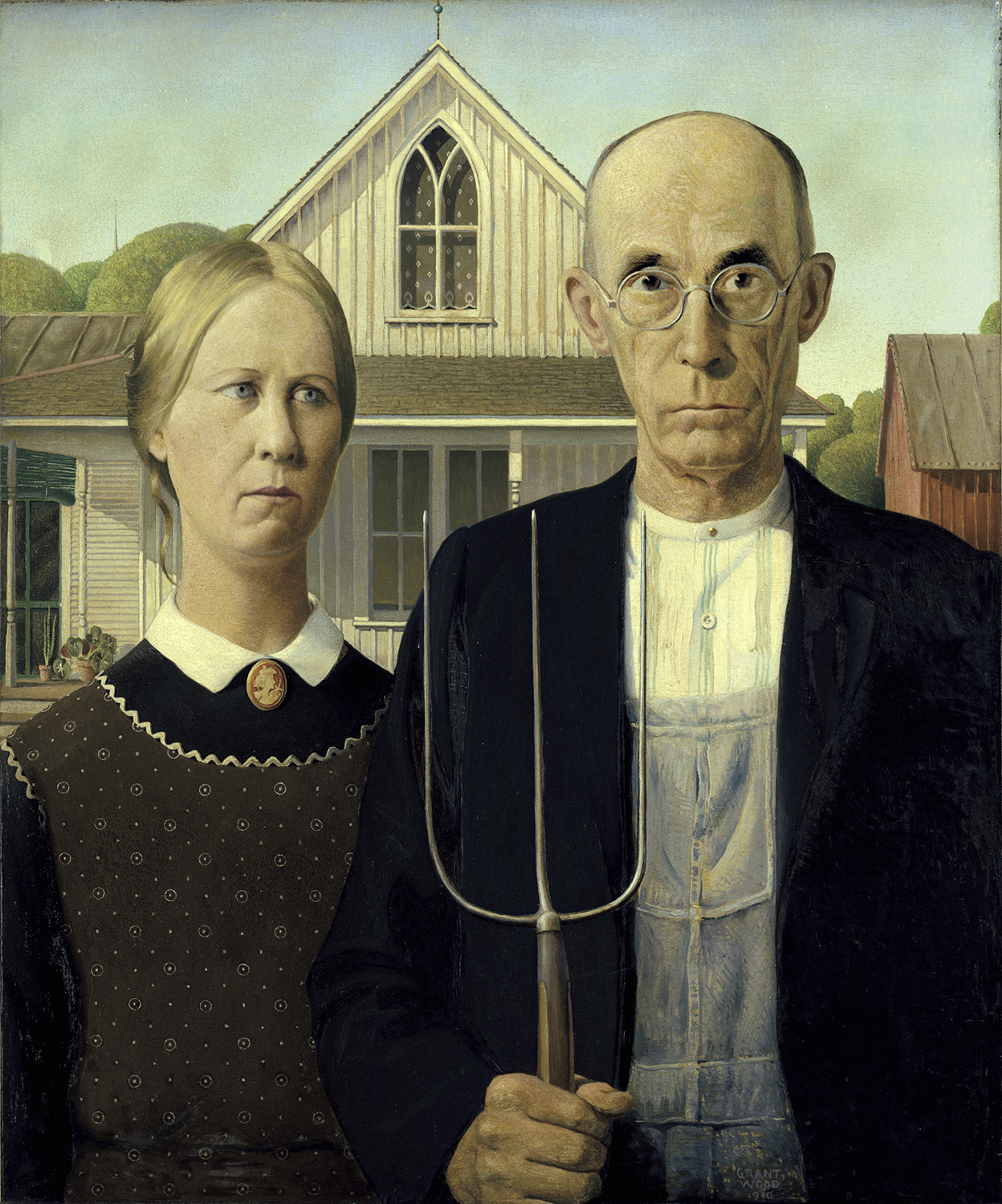

Two hard eyes, two soft eyes, a gothic window, a pitchfork: a diamond-shaped composition burnt into the American collective conscious for almost a century. The haunting double-speak of Grant Wood’s American Gothic reveals a perpetual partition between urban and rural America. Once an inside joke targeting gullible urbanites who relished caricatures of country life, the mischievous wink of the painting has melted into a solemn omen of overarching American disillusionment, as if simply saying, “We told you so.”

Somewhere between those two worlds, I crossed paths with the painting, and it trolled the hell out of me. As its sarcastic barbs have slowly dissolved into a sense of lingering dread that seems to bubble ever-closer to the surface amid Trump’s presidency, I find myself returning again and again to the painting (more out of its own ubiquity than any conscious will). With its sarcastic outer coating now almost fully eroded, it reveals raw truth about America’s fractured identity politics, and provokes a healthy space for parody.

It was the summer of 2009, I was sixteen and visiting colleges in Chicago. It was my first time in a major city and, for a moment, I felt gloriously liberated from the embarrassing, sunburn-peeling, citrus-flinging, reptile-owning, chain-smoking cultural desert of my swampy Floridian youth.

Embraced by the city’s gargantuan glassy towers, the delicious pushes and shoves of strangers actually in a hurry to get somewhere, mediocre street art (its de facto publicness an exciting novelty) and a median age of below sixty-five, it felt like a brave new world: so unlike the vacuum-sealed retiree swan song of Sarasota, Florida. The gritty romanticism of a stuttering subway train as it lurched through a forest of apartment blocks, offering heart-stopping views into real peoples’ lives; the electrifying eye contact with naked couch surfers: the compressed, incidental and relatively meaningless human closeness of city life made my head spin. It was everything Tumblr had promised and more.

“Its sarcastic barbs have slowly dissolved into a sense of lingering dread that seems to bubble ever-closer to the surface amid Trump’s presidency”

Like that kid at the party who doesn’t yet know his limit, I was spending the better part of the afternoon stumbling around the ornate halls of the Art Institute of Chicago, getting drunk on art. Seurat’s pointillist Sunday on La Grande Jatte! Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day! Monet’s hay barrels! Kandinsky’s smeary, lyrical masterpieces! All the paintings I had spent the better portion of junior year idolizing were here, spread out before me, a veritable banquet of culture.

When I found myself in front of American Gothic, my emotional barometers already shot through, some imperceptible force clicked inside the hardware of my brain. The next thing I knew, I was bombastically bawling over the painting’s synthetic Americana. It wasn’t until I got home that I realized the whole thing had been a set-up. Every square inch of the painting that had seemed so tender, so moving, so authentic upon first glance now appears so contrived, such a self-satisfied hack-job of country life that it makes my skin crawl with retroactive embarrassment.

Its mildly comforting to know that I fell into the exact same trap the painting has used to gaslight America for the last century. Now, fully appreciating the painting’s many folds of fakeness—the marathon of artificial loops that the artist, Grant Wood, flung himself through to realize this intensely fabricated scene—I can understand the humour with which it was originally received. But the more I uncover about the painting, it’s increasingly difficult to rest easy on the layer of irony that so comforts city dwellers ogling at it.

Before and after American Gothic, completed in 1930, Wood made nothing of note. There’s ample evidence to show the Iowa native moulded his life around it, frequently changing the characters and inspiration story to suit whatever the trending narrative of any given moment. For a long time, it became the iconic image of American persistence amid the dustbowl of the Great Depression; to suit this idealism, Wood obliterated any trace of his bohemian persona in order to become the good farm boy his patrons wanted to see in him.

At present, its creation myth rests in a rural Iowa safari undertaken by Wood with another aspiring Midwestern painter in the late twenties. During this drive, Wood allegedly spotted the farmhouse he’d include in the painting. Its speculative residents, the subjects of the painting, were “the kind of people I imagine living in that house”, he once said.

“The next thing I knew, I was bombastically bawling over the painting’s synthetic Americana“

All of the painting’s constituent bits hover between truth and fiction, a type of political osmosis that perfectly mirrors the present. The stern-looking farmer is in fact Wood’s dentist; the forlorn wife is his sister. The house is a real house in a real small town in Iowa, yet its features have been radically dramatized (whether Wood received permission from the owners to paint the house is another unresolved detail).

Some historians argue that the painting is so entrancing because it makes such a jumble of art history and American identity. The forward-facing subjects, in their exaggerated verticality, recall Renaissance portraits; that gothic window, a detail Grant later confessed to have made up, stands as a meek gesture towards the stained glass of high Parisian order: jewels of light levitating around dark cathedral stone that was impossibly, almost unbearably ancient for American cognisance. Such hallowed icons of European culture, shamelessly transplanted into America’s mindlessly expansive heartland, foreign architecture rising from golden hills, transforming farm folk into profound dramaturges—the painting offended and stimulated both parties, both flattered and outraged at the fusion.

The painting sweats irony (no doubt Grant learned a thing or two from the Dadaists while living out his flâneur phase), and caused considerable outrage amid country onlookers when it was first exhibited in Grant’s native Iowa. But to the intercontinental city dweller, it became a picture-perfect confirmation of rural Americana. It behaves as a type of looking-glass, a holograph of that mythological, estranged Midwest, forever at the ready to contort itself into the viewer’s preconceived ideas of country living.

“All of the painting’s constituent bits hover between truth and fiction, a type of political osmosis that perfectly mirrors the present”

When it was shown at the 1930 annual exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, American Gothic was described by one of the judges as a “comic valentine”. It has since been rigorously copied, parodied and assaulted into oblivion, becoming a veritable poster child of pop-cultural appropriation, from the Simpsons to Time magazine.

The art world cannibalized it as early as 1942, when civil rights photographer and photojournalist Gordon Parks came in swinging with the portrait American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942). This version removes the disgruntled white farmers, replacing them with America’s largely invisible POC working class. Here, Ella Watson, a black woman working as a janitor in a government building, poses defiantly in front of an American flag hanging on the wall: the pitchfork is switched out for a broom, while the farmer himself has been replaced with a mop in the background.

American Gothic is taxidermied Americana, stuffed with oblique meaning that’s still impossible to digest, almost ninety years later. That’s also its beauty and staying power, and why it is so worthy—and primed—for subversive imitation. Like an analogue meme format that can be drawn upon time and time again, the painting is an instantly recognizable mould, a megaphone awaiting a slogan. The emotionalism that its puckered protagonists refuse to ever fully disclose has swollen to a full vestibule of feeling—whether that’s channelled into potent political outrage, comic relief or a deeper look inward—the painting and its degenerates are an increasingly welcome offer in these troubled times.

While I’m occasionally still pricked with hot flashes of embarrassment upon encountering the painting, I’m grateful I was trolled by its shape-shifting status, which has become the perfect metaphor for America’s fictitious identity complex and a constant reminder to never take anything—not least rural America—at face value.