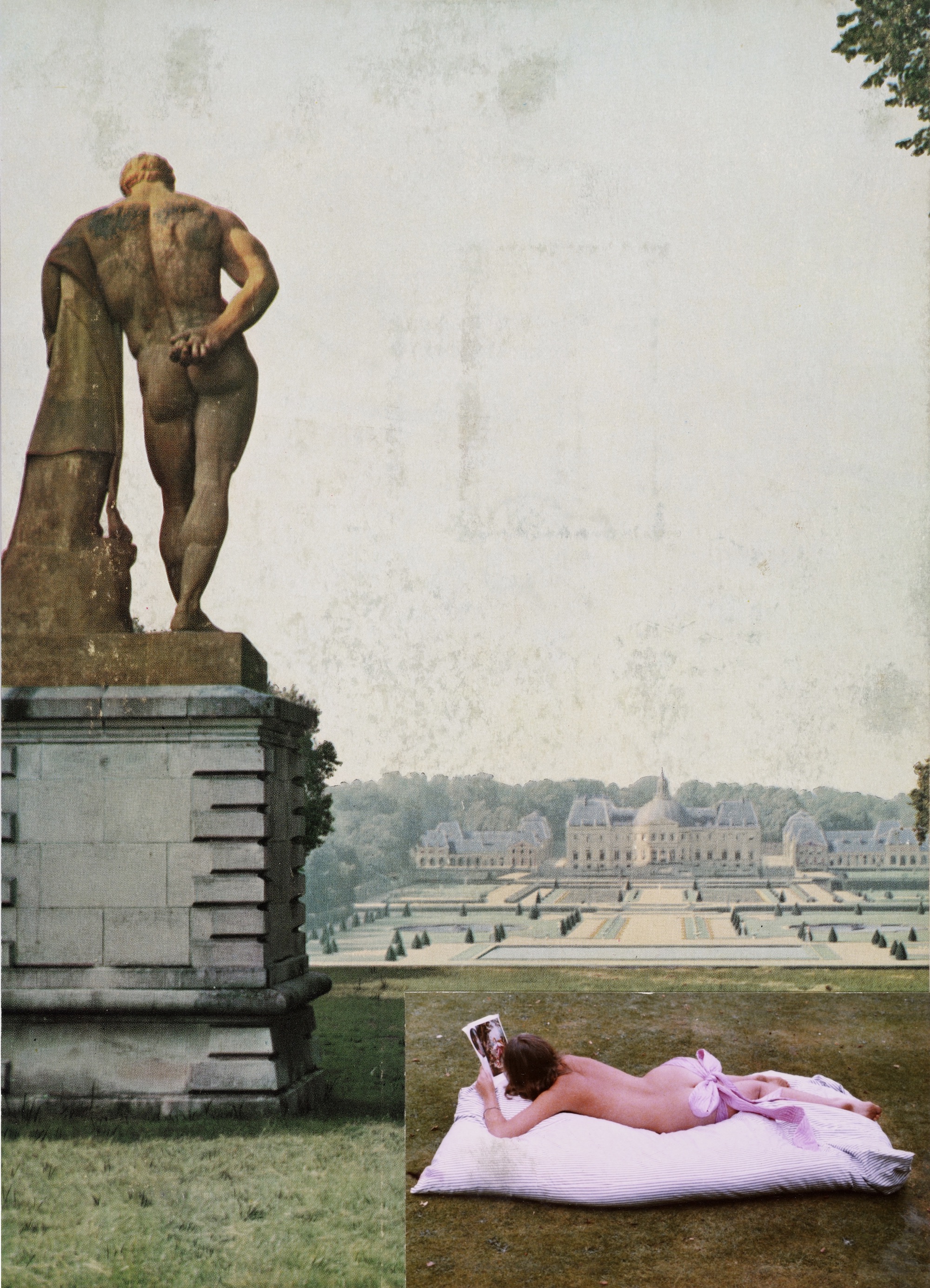

For a long time, the mythology of the artist was concentrated in the countryside. Entire movements within the western art historical canon like Romanticism, Rococo and Impressionism bloomed from luxurious representations of the rural as a pastoral oasis: the pseudo-simplistic utopian ideal brought to life by the delicate swish of an artist’s brush. These representations were far from naïve; to look upon the landscape and possess the means with which to depict oneself nestled amongst its wild abandon was a pure symbol of power and authority. But these images also reveal a dark and undeniable truth about who, precisely, is permitted to look and be seen. Throughout history, this has proven to be a select few very rich, and very white, members of the aristocracy.

Nowhere is this truer than in England, where land ownership has held onto its symbolic power since the final and most contentious wave of land enclosures in the mid-eighteenth century. Landscape painters celebrated by the English popular imaginary including Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable were fully entrenched in this world that so readily blended reality with representation, political power with pseudo-nature and invisibility with exclusion.

The Lie of the Land, the current exhibition at the newly opened MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, investigates that very English obsession with the land and its ties to race and class politics. From the famed eighteenth-century landscape painter Canaletto to video artist Lawrence Lek, the exhibition takes an expansive look at how artists have traditionally represented this pastoral utopia, critiquing its implicit social, political, and economic regulations; the exhibition also shines a spotlight on the contemporary artists re-examining the rural amid the popular imaginary, both in and outside of art culture.

Standouts here are the sculpture by Yinka Shonibare that greets visitors upon entrance, as well as a series of self-portraits by British artist and social worker Jo Spence. Both works expand our idea of the rural; Shonibare’s gentry are dressed in a dapper outfit made from the seemingly ubiquitous African-print fabrics sold on high street markets across England. Coated in a flashy bootleg Chanel print, Shonibare makes a tongue-in-cheek pointer towards the true nature of such portraits, whose subjects touted their wealth through their own rural representation (perhaps the original humble brag). Meanwhile, Spence’s tender lens captures queer and obese bodies typically excluded from the genre.

“To look upon the landscape and possess the means with which to depict oneself nestled amongst its wild abandon was a pure symbol of power and authority”

Over at the Prada Foundation in Milan, a new exhibition (titled Whether Line) presents artist duo Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s latest foray into a surreal, unnerving parallel universe. Part amusement park queue and part insane asylum, shrieking speakers drip with a thick midwestern drawl on a trail that eventually leads into a cavernous old water tank, where a life-size hobby barn has been erected. Rich autumnal scenes of sun-splotched maple trees, rustic barns and woodsy forest watchtowers populate the landscape, as does a mounting sense of unease. In the first screening room, the feature-film length Plot Front (2019) can be viewed from the preferred seating arrangement of country living: rows of white rocking chairs. The pair have ventured into the great outdoors.

Trecartin appears here in drag as the film’s leading character, Neighbour Girl. For the next hour and forty-five minutes, Trecartin’s alter-ego can be seen engaging in various acts of gaslighting and self-actualizing; from bickering with the neighbours to partaking in forest cardio and ultimately constructing a forest watchtower to spy on the others in a fit of paranoia. For better or for worse, Plot Front doesn’t stray too far from its source. These kaleidoscopic scenes stem from Athens, a 25,000-person college town in rural Ohio where Fitch and Trecartin have spent the last two years inhabiting a stage set on a hill on Prada’s pocket. The work on show at the Foundation indulges all the tropes of small-town drama—albeit without actually engaging with the locals.

2016 property records in Athens show the duo purchased a blue barn—the same building that appears in their new film—for $215,000. Building this elaborate stage set involved large-scale changes to the landscape and irritated the artists’ next-door neighbours, who claimed the project did serious damage to their property. This argument wouldn’t mean much had it not seriously impacted the narrative of Plot Front, which, as its title suggests, doesn’t dig much deeper than these surface level tensions.

That Plot Front seems to focus more on Fitch and Trecartin’s own existential experience of relocating from LA to rural Ohio to make an art film ends up revealing more about their narcissistic oversimplification of “country living” than any real insight into what the town of Athens might actually be like to inhabit. An opportunity to engage with the community by transforming the specially-built lazy river into a public attraction post-filming was swiftly declined by the artists.

When did the countryside become so alien, so antagonistic? The myth of the artist as urbanite was born in the mid-twentieth century and grew with the rise of American modernism, which placed an obsessive value on the evolving metropolis as a progressive salvation from the dark despair of World War II.

In the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, radical performance artists like Marina Abramovic, Joan Jonas and Laurie Anderson descended upon the seedy streets of New York, transforming the urban realm into a powerful stage set for interrogating the political and personal. Yet with the peak of club culture of the eighties and nineties, a dizzy high combined with the hype of Pop and its ready embrace of mainstream culture, the artist as city slicker had become the predominant (and predominantly masculine) narrative of modern and postmodern art.

Decades on, and artists have continued to base their practices primarily within the urban realm: international art cities remain the holding grounds for lucrative galleries and art fairs, as well as a symbol of education and worldliness. As the division between the uber-rich and working class continues to intensify, this boundary becomes ever more antagonized. Yet there is also a returned interest in the rural, part of a larger movement to expand and multiply its definition while acknowledging its often problematic representation in contemporary visual culture.

“Just how far do the tropes that we prescribe to the rural end up ruling us?”

Artist collective MyVillages are one contemporary example of a group investigating the multifaceted relationship between the urban and the rural. Organising collaborative projects in villages and city institutions (including an ongoing public events programme at Whitechapel Gallery in London), the team operates with the intention to broaden “the rural” as a shareable cultural ground while applying pressure to how hegemonic ideas of culture are wielded in urban contexts. “There is a clear power hierarchy between country and city, and a long tradition for it, especially when it comes to our image of culture,” co-founder Antje Schiffers says.

Meanwhile, artist-filmmaker duo Stephen G. Rhodes and Barry Johnston, collectively known as Unknown Friend use their lens to expand our understanding of the rural. Sivilization’s Wake (2018) is a tragicomic redux of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, using a misinterpretation of Mark Twain’s seminal novel to unpick the race and identity politics still lingering some 130 years later. The result is equal parts mythological, moving, dark, surreal; it glimmers with hope.

Dark forces will conspire in the woods; any B-list horror movie will teach you that much. But just how far do the tropes that we prescribe to the rural end up ruling us? Half of the world’s population lives in the countryside. Too often are these regions and those that inhabit them oversimplified, and their existence reduced to a sequence of hackneyed scenarios and dismissive descriptors. Dismiss the power, the magic and the majesty of the rural if you will, but do so at your peril.