While admittedly I wasn’t alive yet in 1977, the year conjures for me London’s grubby punk culture and New York’s Bowery crawling with wonderfully bratty loudmouths. But for many people, 1977 couldn’t have been more different from the burgeoning underground music scene, as this heartwarming, sunshine-filled documentation of life at summer camp demonstrates.

Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah is photographer Andy Sweet’s saccharine but wryly humoured love letter to long hot summers, first crushes, and the strange rituals and sensations of pre-teendom that leave many feeling at the mercy of their rapidly changing bodies. He perfectly captures the months when young people suddenly have to contend with growth spurts seemingly overnight, which can impinge upon the carefree running and jumping of childhood, and signal a passage into adulthood that many aren’t fully ready for.

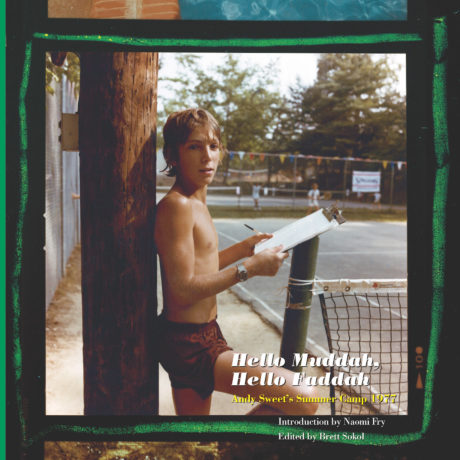

Sweet shot the series when he was 24, during his time studying art on the University of Colorado Boulder’s MFA programme. According to Brett Sokol, co-founder and editor of Letter16 Press (the non-profit publishing house behind the release of Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah), he was already a self-described “documentary photographer” on a mission to tell his “own story about the truth of something”.

“Summer camp was ideal for observing moments both profound and offhandedly joyous”

For this series, Sweet selected a story he knew well, focusing on the camp for secular Jewish kids at Hendersonville, North Carolina’s forest-surrounded Camp Mountain Lake, where he had spent every summer since 1968. He first attended as a camper, then as a camp counsellor and photography instructor. According to Sokol, Sweet’s students were “essentially younger versions of himself: secular Jews from South Florida, straddling the lines between societal insiders and outsiders, comfortably middle-class yet raised within a deeply conservative region filled with lingering traces of open anti-Semitism.”

- Andy Sweet, Camp Mountain Lake, Summer 1977, from Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah

These camp photographs formed the basis of Sweet’s MFA thesis, in which he explained his image-making approach as one in which “photographs are not the reason of their subject matter”. His images, shot on a Hasselblad, give insight beyond the voyeurism that can come with documentation, integrating Sweet the photographer as a familiar presence for his subjects behind the lens. “The subject matter is the reason… Belonging, knowing and understanding, before picking up the camera, is the most determining factor,” Sweet wrote.

He conveys a sense of familiarity and intimacy with not only the people in the images, but with the very essence of the camp, including its activities, routines, adolescent crushes and everything else that was engulfed within its eight week-long, self-contained world. Sweet’s thesis delineated that the camp environment was “an ideal one for observing moments both profound and offhandedly joyous”, Sokol explains.

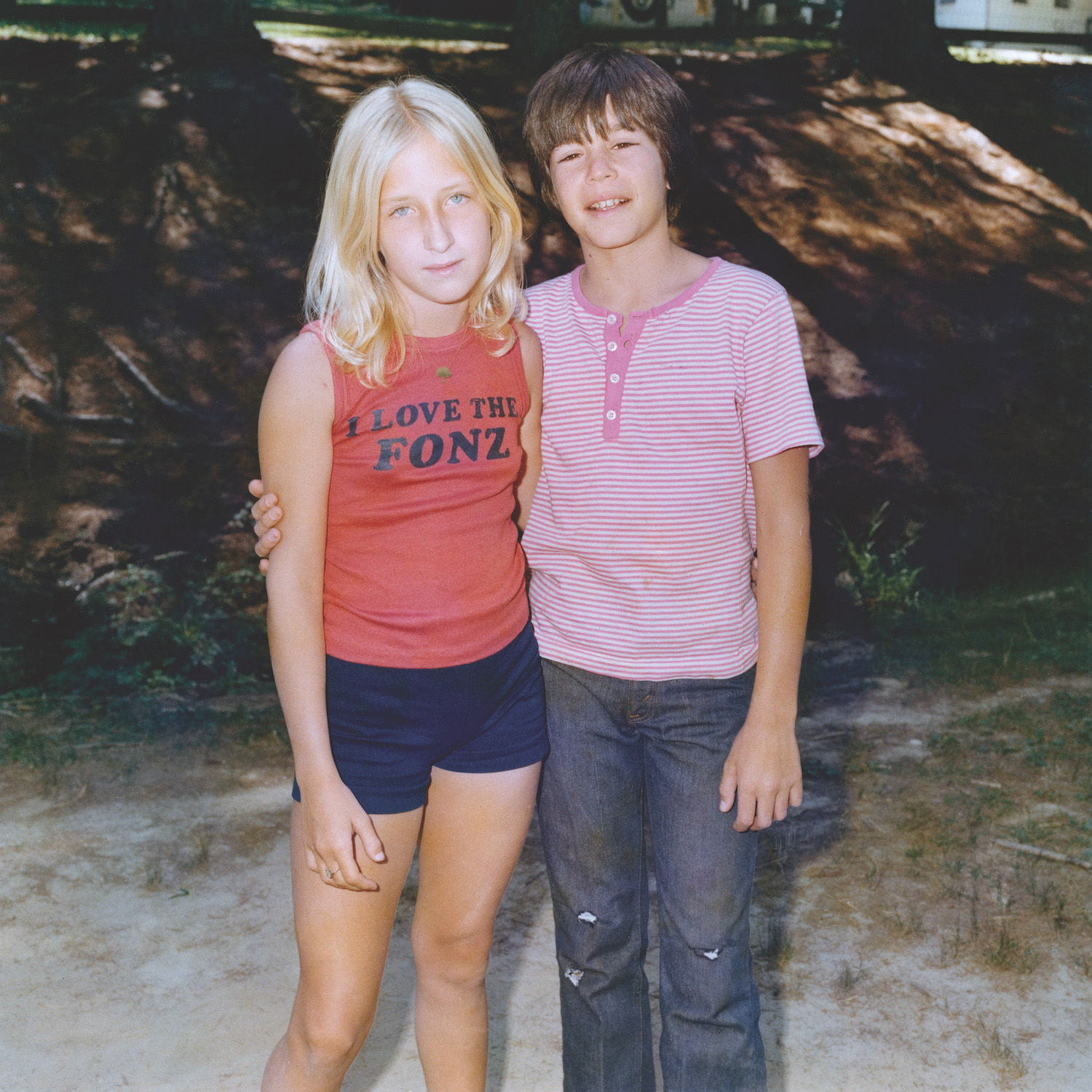

He adds that Sweet’s photos provide “a knowing portrait of the era’s fashion, pop culture and frank expressions of adolescent sexuality… a classic coming-of-age story”. Just take the unsettling image of an adorable, geeky girl posing with one knee a tennis court floor, wearing a t-shirt that bears the simple statement, “SEXY”.

- Andy Sweet, Camp Mountain Lake, Summer 1977, from Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah

“He conveys a sense of familiarity and intimacy with not only the people in the images, but with the very essence of the camp”

This notion of image-making as a representation of “truthfulness” is played out through Sweet’s use of brightly saturated colours, which make it feel as though that 1977 sunshine is still beating down as hot as ever. At the time, colour images weren’t taken seriously by the art world. They were deemed the preserve of “advertising, fashion, National Geographic-type travel pictures, nature pictures, old-fashioned arty abstractions of peeling walls and European traffic signs”, as then-New Yorker photography critic Janet Malcolm wrote at the time. But as Sweet saw it, “colour is a device to include more reality”.

On graduating, Sweet and his friend and fellow photographer Gary Monroe set about devoting the next decade to what they dubbed the “Miami Beach Photographic Project”, which essentially meant documenting the local area which was soon to become gentrified. Tragically, after five years, the project was cut short by Sweet’s murder when he was just twenty-eight years old.

Before his untimely death in 1982, Sweet had shot both his summer camp series and one that has since been organised into a book called Shtetl in the Sun: Andy Sweet’s South Beach 1977–1980

, released last year by Letter16 Press. The images depict Miami Beach’s elderly Jewish community, and provide a beautiful counterpoint to his shots of young campers. Both series portray a community of people on the brink of a new chapter of life that neither age group seem fully resigned to.

“Sweet’s photographic gaze was always tempered by a decidedly non-scientific sweetness, humour and sadness”

“Whether observing the South Beach shtetl or the North Carolina campsite, the anthropological was always Sweet’s starting point, though his photographic gaze was, too, always tempered by a decidedly non-scientific sweetness, humour and sadness,” writes Naomi Fry in the introduction to Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.

“If the photographer’s Miami Beach series felt like something of an elegy for a dying tribe, then his campers seem to veritably burst with cocky new life… They have arrived in paradise, away from their families and among their peers, and they are ready to take on the new personae that this shift allows for… Sweet’s pictures are a celebration of bravado and gawkiness.”