London- Anna Uddenberg has become known for her sculptures of hyper-sexualised (and hyper-flexible) faceless female dummies adorned in futuristic, utilitarian luxury apparel and flaunting synthetic hair and acrylic nails. Frozen in extreme positions or poses that push “sexy” to the brink of absurdity, these highly instagrammable figures hold up a mirror to contemporary culture’s obsession with self-styling and our being locked in a mode of “watch[ing] ourselves as someone else,” as Alice Jardine would have it. Whenever they appear, whether as standalone figures or complete with matching furnishings, Uddenberg’s females tend to produce environments that are themselves confrontational, and HOME WRECKERS at The Perimeter, the first UK solo exhibition by the Berlin-based Swedish artist, is no exception.

I meet Uddenberg here for a chat as she prepares for the exhibition’s opening. Greeting me at the door is “Tanya” (2021), one of Uddenberg’s ten sculptures in the exhibition, performing a deep squat with her stroller, whose most crucial component—the baby seat—is entirely missing. An object abstracted from its function, this prop and overall scene disclose something of the show’s orientation, for the latter, and Uddenberg’s practice more generally, deals in simulacra or the seductive force, if you like, of appearances. Seated on a large leather sofa, which I soon realise is part of the show (it’s “corporate grey”), I ask Uddenberg to comment on this dimension of her work. Returning to her earlier performance-based pieces, she tells me she’s “been interested in the idea of performed authenticity for a while.”

Girlfriend Experience, a performative experiment in self-commodification, was made in 2009, “the same year I signed up for Facebook,” Uddenberg recalls. When I ask if the rise of social media was really the catalyst for this kind of work, however, she chooses to privilege another, more unexpected source: “I was going back and forth to Frankfurt, where I was studying at the time, and I spotted this ad on the plane offering the option to purchase different, unique experiences, like ‘be a model for a day”’ or ‘be a rockstar’ … I found this idea of a commodified experience very interesting, not knowing that we were entering an era that was going to be all about that.”

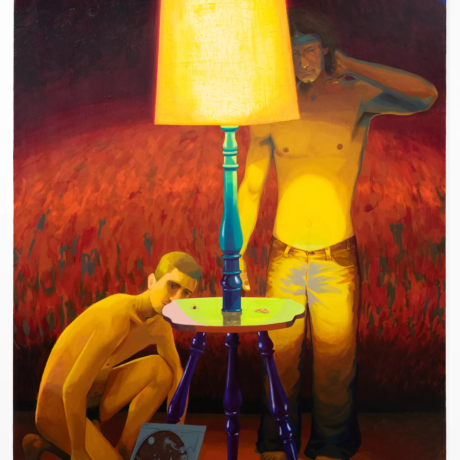

As I try to picture this weird, airborne advert, I am reminded of Phil Collins’ This Unfortunate Thing Between Us (2011), adopting the language of telemarketing for a fictional program called TUTBU TV, auctioning real-life experiences. Familiar with (and a fan of) Collins’ work, Uddenberg begins to talk about his karaoke trilogy, The World Won’t Listen (2004–2007). She tells me that something of the spirit of karaoke (understood as a miniaturised form of spectacle) infected her “it girls” graduation show at The Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm back in 2011, which was “really the starting point for what was later to translate into a sculptural practice embodying this strange, mutant subjectivity of the present.” Whereas karaoke performers often embrace their amateurism, however, Uddenberg’s “it girls” and her sculptures at The Perimeter strive for—so as to play on the notion of—“effortless” perfection. Disconnect (airplane mode) (2018); Corporate Grey / External Spine (2021); Climber (Pierced Rosebud) (2020) … these works centre sleek, hyperreal bodies whose proportions and athleticism are the stuff of dreams, or rather, fantasy. The leisurely female of Disconnect (airplane mode), indeed, seems to have jumped straight out of a hentai porn catalogue. So spectacular is Uddenberg’s manipulation of surfaces in these works—combining materials like clay, fur, velvet, steel, wood, and leather, as well as ready-found objects like shoes, bag straps, and leather harnesses—that the fact that they were sculpted entirely by hand becomes easy to miss. Uddenberg herself forgets at times: “You’d think that after being in the studio with this piece of clay for so long you’d know what you’re looking at, but at one point it acquires this life of its own and starts speaking back to you.” What is it that it says, I wonder?

Uddenberg’s work appears to me to offer and negotiate a space determined by the confluence of different forms of fetishism: the fetishisation of the female body, historically hijacked and exploited by advertising culture as Uddenberg herself notes in various places, but also, more broadly, and I guess the two are related, the commodity fetishism of capitalism. Uddenberg’s world, indeed, is a reflection of late capitalist consumer society, one where, as Gail Faurschou puts it, “commodities produce bodies: bodies for aerobics, bodies for sports cars, bodies for vacations, bodies for Pepsi, bodies for Coke, and of course bodies for fashion—total bodies, a total look.”

Of course, Uddenberg’s females exhibit a degree of agency; they quite obviously perform something, but their encounter produces a nervous energy that, I think, compels us to ask: according to whose desire? The figures serve what Susan Bordo calls “cultural plastic”—a term pointing to the, at heart, the disciplinary character of our preoccupation with appearance and self-transformation—and do so in environments that, much like those we habitually find ourselves in out there, in the so-called “real world,” are themselves mediums administering a weird admixture of comfort and control. In the obsession with self-styling or ‘sculpting’ reflected by Uddenberg’s figures lies also a third kind of fetishism to be discovered in her work: the fetishisation, that is, of the technology of the self, aided by new media technologies and linked to the emergence of what Jean Baudrillard, in Symbolic Exchange and Death, would call “a planned narcissism […] associated with the manipulation of the body as value”—a condition that is itself effectively captured by Uddenberg’s portrayal of selfie-stick anality in Journey of Self Discovery (2016) on display at The Perimeter.

The scene is kind of pathetic, but then again, so are we (if the works in HOME WRECKERS make us uneasy, that’s because the future they foretell has already arrived). Uddenberg, anyhow, is not judging. Commenting on the extravagance of her contortionists, serially folding themselves into awkward-yet-seductive positions where subject and object come to coincide, a super-laid-back Uddenberg confesses: “There was a time when I did that, I know what it’s like to be this out-of-control femme, and that’s the difference between me and Hans, for example.” The artist is referring here to the German Surrealist Hans Bellmer, whose mid-1930s dolls offer an obvious yet false progenitor for her figures. Being “all about the effort,” what Uddenberg offers or (re)stages with HOME WRECKERS is a head-to-toe phantasmagoria of signifiers (it’s no accident her females sport brand-name objects like Balenciaga Crocs) that betray not so much an erotic obsession (the Freudian fetish), but a semiotics of the feminine—or an elaborately coded femininity—that brings Uddenberg’s work closer to the practices of, say, Cindy Sherman and Rosemarie Trockel. To borrow a line from Baudrillard, “hot, sexual obscenity is [here] followed by cool communicational obscenity.” “The materials that I’m working with function like triggers to me—layers of references, much like memes, reproduced, copied and mutated, while forming new meanings,” Uddenberg points out.

This emphasis on a political economy of the sign also reveals an understanding of gender and sexuality as clearly severed from the moorings of biological essentialism. In the press release for HOME WRECKERS, the artist, indeed, is found postulating that “maybe the fake is more authentic than whatever you think of as authentic”—an idea that not only supports a “technobody”-approach (think Donna Haraway, Paul B. Preciado, and Alice Jardin, among others) to her sculptures but which also serves to return us to the conceptual frame of fetishism, insofar as “the etymological origins and philosophical history of the word itself point,” in the words here, of Emily Apter, “to the artifice (facticius) present in virtually all forms of cultural representation.” If, as Uddenberg seems to remind us with HOME WRECKERS, the subject (as fetish) is produced and remade in and through performances that involve the appropriation of disparate signs and elements extracted from flows, free and manipulated, in circuits structured by desire and affect—all this, in the context, always, of technology-bound consumer culture—the interesting question is not “Is it real (enough)?” but: What else can we do with it? How do we tech/science-fiction ourselves otherwise?

Words by Lilly Markaki. Images courtesy the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.