London – Stepping into Rose Easton’s eponymous gallery space in Cambridge Heath, a black carpet extends from beneath the door, its edges forming jagged points. Crossing this threshold, you find yourself in the hallowed space of José, Arlette’s first solo exhibition with Rose Easton.

The show is composed as a church interior or religious space, which first becomes apparent by the placement of cannily named Testicle 1 (2023), a piece carved into volcanic rock, which is hung high in the gallery space. This placement is reminiscent of a religious icon hung in the home or on the church wall, presiding over all who enter the space.

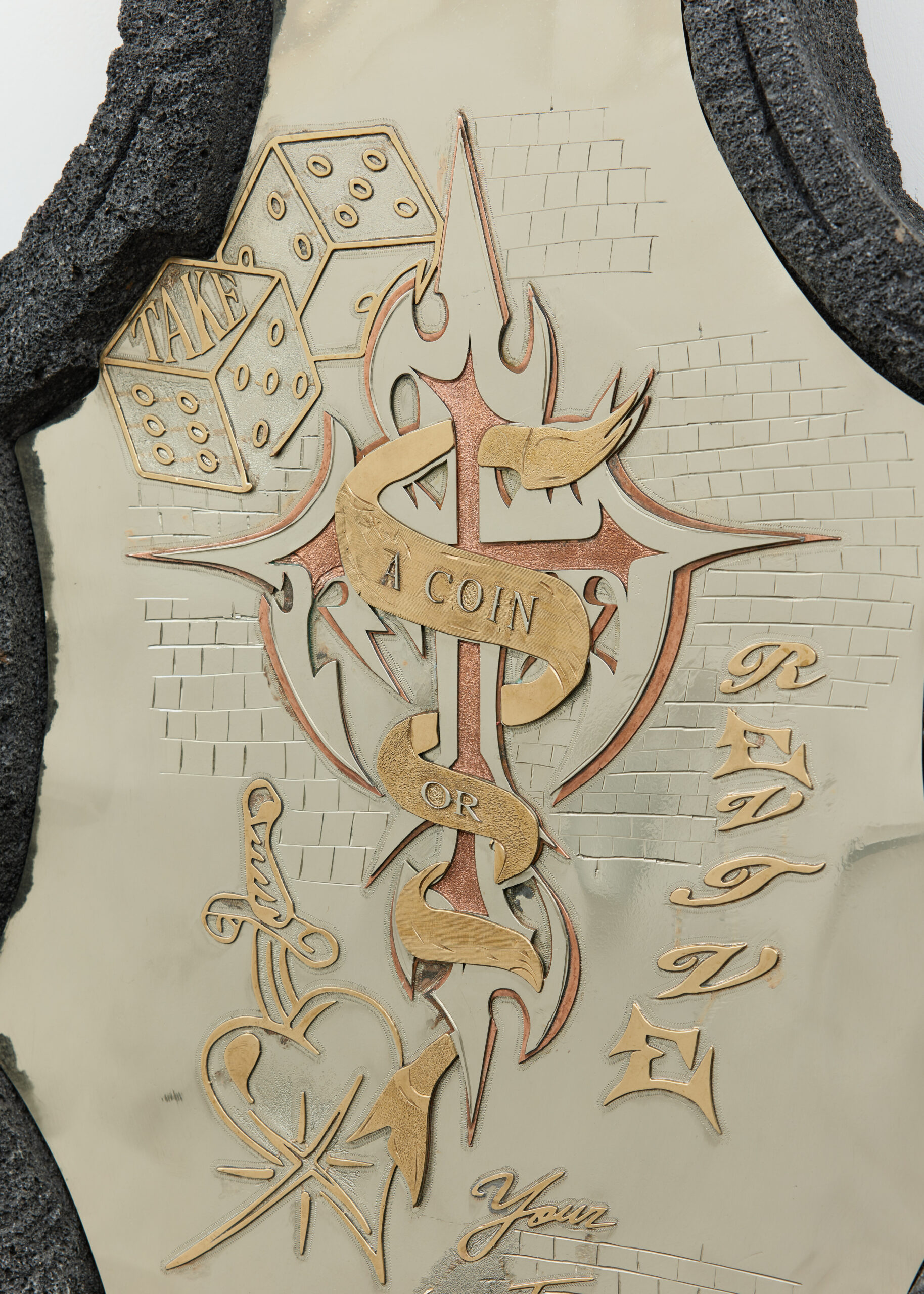

As in a church, where the ornamentation converses on holy and biblical narrative, the works here, too, are in dialogue: their narrative speaks of Arlette’s personal mythology through metaphor and symbolism. On the opposite wall hangs Holy Water (2023), a font which holds no water as such but the silver inscription of the word “José” – which perhaps serves as the holy substance here. There are inscriptive epigrams featured on the bronze panel of the font; “Your worst memory” is engraved on a banner wrapped around the cross against a brick pattern. To the side of this, “A COIN OR” features alongside the motifs such as the rolling dice, evocative of gambling, which delves into the semiotics of such entertainment, imbued with more toxic ideas of masculinity. The work is a composite montage of signifiers.

The many words inscribed in silver throughout José make up tender but fragmented love letters, where their entirety is obstructed: they remain tantalisingly out of reach, cloaked in personal and private enigma. We can only wonder and piece together these meanings, which become a tapestry of Arlette’s memories, personal history and what is sacred to her. This approach enjoys the viewer’s search for meaning in works, confusing and obstructing one ultimate message.

In conversation with Rose Easton, she tells me that she is drawn to artists whose practice can be considered a form of world-building, designing a temporal space from the ground up, creating an environment, culture, history and geography. This is certainly true for the all-encompassing domain forged within José, where you are privy to a private and tender world in which Arlette confronts her dreams and demons. Born and raised in Mexico and currently living in Mexico City, Arlette, a multi-disciplinary artist engages in a dialogue between the past and the present. By way of sculpture, moving image, performance, and fashion, she delves into the complex thematics of religion, gender, and sexual identity.

José offers meaningful but shielded glimpses into Arlette’s personal cosmology. The works unearth a private narrative, a familial dialogue reminiscent of a conversation with a parent or relative. After a recent return to Mexico, Arlette explored her newfound connection and understanding of both her paternal relationship and Zacatecas in Mexico, a city known as a silver mining hub and the hometown of her father.

Arlette’s craftsmanship is a practice she has been honing since childhood. The materials she employs are native to the place of her family’s origin, serving dual purposes in both art and daily life in Mexico. Featuring intricate layers of techniques and various metals, this choice of material is a dichotomy: hard elemental materials that have significance in cooking and domesticity are transformed into forms that exude a recognisably sacred quality. Arlette revisits her childhood, and her practice reanimates her father, casting her memories of him in the metal sculptures encased within the sanctity of José.

The exhibition further explores Arlette’s relationship with animals. Themes of life and death emerge in a playful yet explicit dialogue, reflecting on childhood, play, and innocence. In José (2023)’, a cockerel, wings spread, cast in bronze and silver, launches into the poise of attack. Surprisingly, though, the rooster signifies redemption and forgiveness in Mexican culture, another dichotomy of Arlette’s work. In the exhibition, animals, especially in such sacred conditions, could even be perceived as apotropaic symbols, designed to avert harm or evil influences, adding a layer of mystique and perhaps intended to protect her childhood memories encased within the pieces.

As a child, Arlette was raised on a ranch, surrounded by animals and harboured dreams of breeding horses and becoming a rancher, a dream that still lingers within her. In Caballo Prieto Azabache (2023)’, a newly born foal, still blue, emerges from its birthing sack – a grotesque vision, made mythical in a tender moment of parturition, a creature-like wing emerging from the side of the foal.

Across the room, Trapichero (2023), a structure part horse, part mythical beast as a coin-operated arcade ride rocks to and fro. Onto the stirrups on either side, the words “RECONCILIATION” and “MY GOD IS REAL” are etched- the base of the ride reads: “I MISS MY INNOCENCE.” These inscriptions are a rumination on grief, on the loss of childhood. But they are not purely melancholy. There is a tangible message of encouragement- urging the viewer to continue looking for childhood wonder despite all odds.

Throughout the exhibition, multiple narratives and paradoxes unfold, where tenderness and softness converge with a hard and jagged, almost impenetrable exterior, a duality which calls to mind the complexities, nuances, and polarities inherent in masculinity. More broadly, she reflects on her own experience of hyper-masculinity in Mexican culture. Even in her practice, Arlette navigates the traditionally masculine domain of silver welding and rock carving, as well as the use of heavy tools and machinery.

Assembling such material and narrative within the holy setting of José serves as a contemplative arena to meditate on the origin of hypermasculinity. Religious methodology created the groundwork of the patriarchy and is, to this day, a mechanism steeped in toxic influence on masculinity. By being introduced to this ecclesiastical theme, we can identify more of the works as emblematic of icons, crucifixes, and relics, which are cast in impenetrable silver, a metal both everlasting and powerful. In Mexican culture, it symbolises protection, connection to loved ones, and spirituality.

Arlette’s attention to detail is meticulous, treating fashion items with the same reverence as sculptures. She treads on the edge of fashion, where her pieces reflect an undercurrent of anxiety, utilising methodologies common to both fashion and art: metaphor, narrative, and even craftsmanship. Arlette challenges the fashion-art binary boundary, blurring the lines between the two worlds. She recently accessorised Rosalía and previously designed Kendrick Lamar’s stage outfits for his European tour and Travis Scott get-up for the cover artwork of his album UTOPIA. Alongside this star-studded clientele, Arlette makes pieces for her friends to wear, creating a personal and intimate dialogue with them.

José pitches the commercialisation of art against spiritual principles, as seen in the vending machine built into the wall within the gallery space. From it, Arlette’s trucker caps, belts, and jewellery can be purchased, considering the gallery’s often hidden reality as a retail space. Simultaneously, this introduces a playful interaction with the gallery goer, which is juxtaposed against the sobriety and intensity of the other works. Perhaps the silver-encrusted jewellery and belts serve as relics or pocket icons: works of art in their own right, here talismanic and sacrosanct.

Her fashion pieces, silver-encrusted belts and trucker caps are adorned with triple XL phrases, their explicit connotations being often unidentifiable to the ultra-masculine men who have worn them. This further underscores the exhibition’s theme and Arlette’s intention of concealing and playing with meaning and identity in more humorous ways. She toys with the idea of the fading of hyper-masculinity and fearlessly incorporates aesthetics and materials that are both loud and brazen. Through this playful push and pull, the aggressive aesthetic and formidable materials belie a tender message behind it, where she encourages a return to child-like innocence, gentleness, and friendship.

José is a sacred space in which to meditate upon ideas at the root of contemporary society: hyper-masculinity, identity, faith, consumerism, and the commodity. Arlette delves into the social imaginary through the lens of hyper-masculinity, with brief, shielded glimpses into her personal cosmology, inspiring awe and introspection. Sanctifying her memories, she frees them and cleanses them of any traces of impurity within her self-created holy space, the church of Arlette.

Words by Rosie Fitter