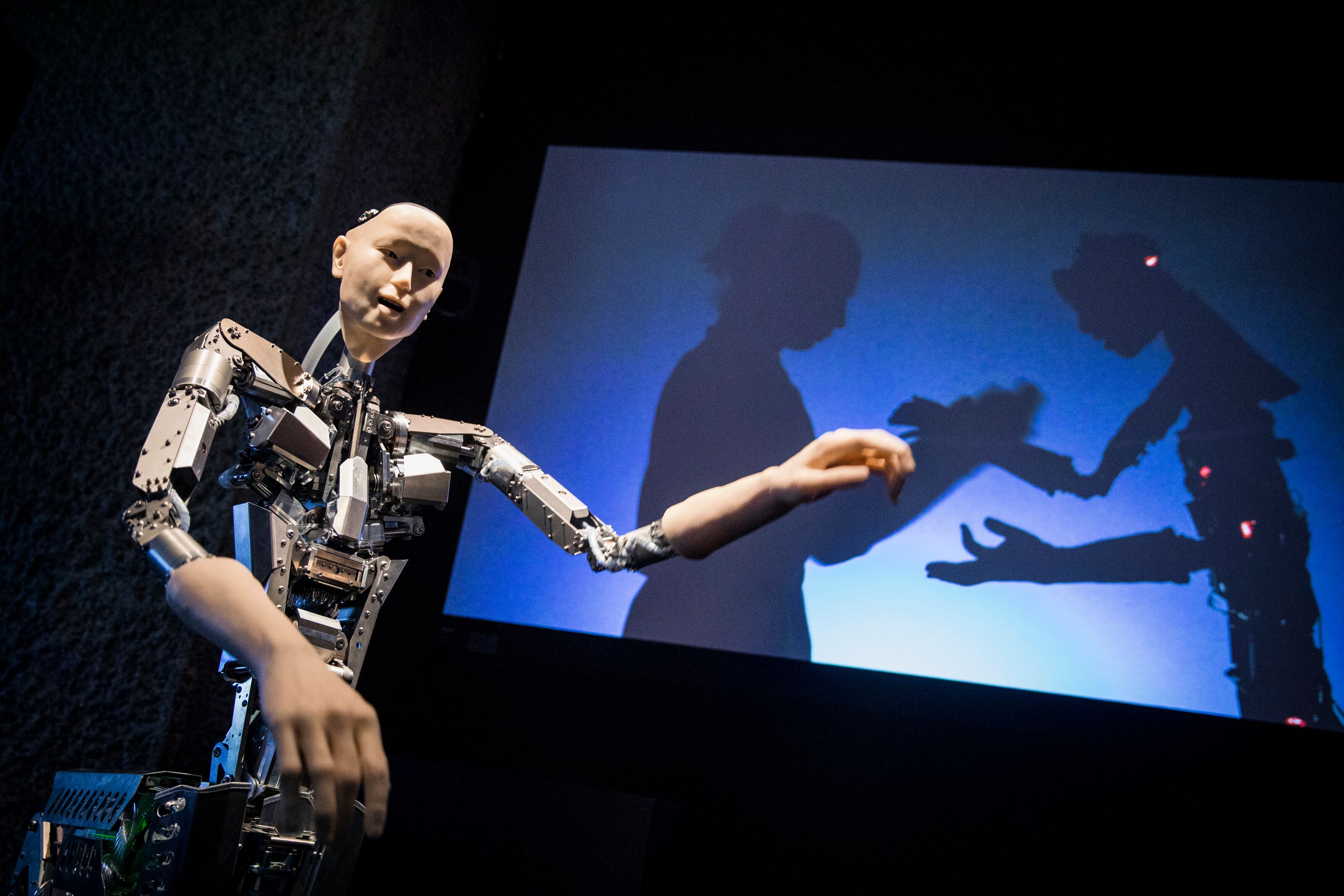

In AI: More than Human, the Barbican’s current exhibition on artificial intelligence, two ideas are made abundantly clear: no, robots won’t steal your job, and no, they definitely won’t make better art than you. Instead, the motley assortment of quasi-autonomous objects, experiments and informational plaques on display manage to plant a devilishly anthropomorphic seed, asking: what does our obsession with AI suggest about us?

Unfortunately, the hardware of the show lags way behind this lofty question. Starting out heady with Golem of Prague, a Jewish myth about a stone beast leaping to life, the cluttered halls of the Curve gallery quickly descends from mystical pondering to feeling like a scientist’s jumble sale. Fleshy silicone faces adhered to robotic arms and multiple malfunctioning interactive displays pair with outdated theories on robotics. Vastly oversimplified explanations of AI terminology, confusingly pasted across the winding walls, meekly attempt to restrain the robot dogs, roombas, and psychedelic computer-generated landscapes that are clearly having way more fun than the befuddled visitors.

Within the first few moments of AI: More than Human, the show abandons its premise of exploring a sci-fi future where artificial intelligence ascends its human bonds and self-actualizes in psycho-robotic enlightenment. Instead, the exhibition inadvertently reveals a larger, more telling truth about the fusion of contemporary art and AI.

Today’s artists aren’t interested in AI being “more than” anything. Rather, they’re interested in dissecting the multitude of ways this technology is deeply embedded within, and increasingly propping up, the powerful global systems that govern our lives. They dig into the awkward truth that, for all our mock-outrage over dubious ethics of the tech elite, we sit complacently in the middle of this relationship, eagerly welcoming Silicon Valley giants to mine our data in exchange for one more cat meme or swipe right. Like a nefarious software update that auto-installs overnight and sends your shitty iPhone 6 to the grave, it leaves the distinct impression of being hacked, of waking up with a terrible tech hangover that we’re prone to repeat.

Teasing out the layers of empathy, entertainment and desire that forms AI’s pressure bond with humankind, artists like Kate Cooper and Lawrence Lek

explore the neurotic and at times violent impact of this technology on our bodies and environments. On the other end of the spectrum, Ian Cheng and Lauren McCarthy take stabs at the uncertain territory that could enable us to develop a deeper bond with these systems through interactive and performance-based work that muddies the line between man and machine.

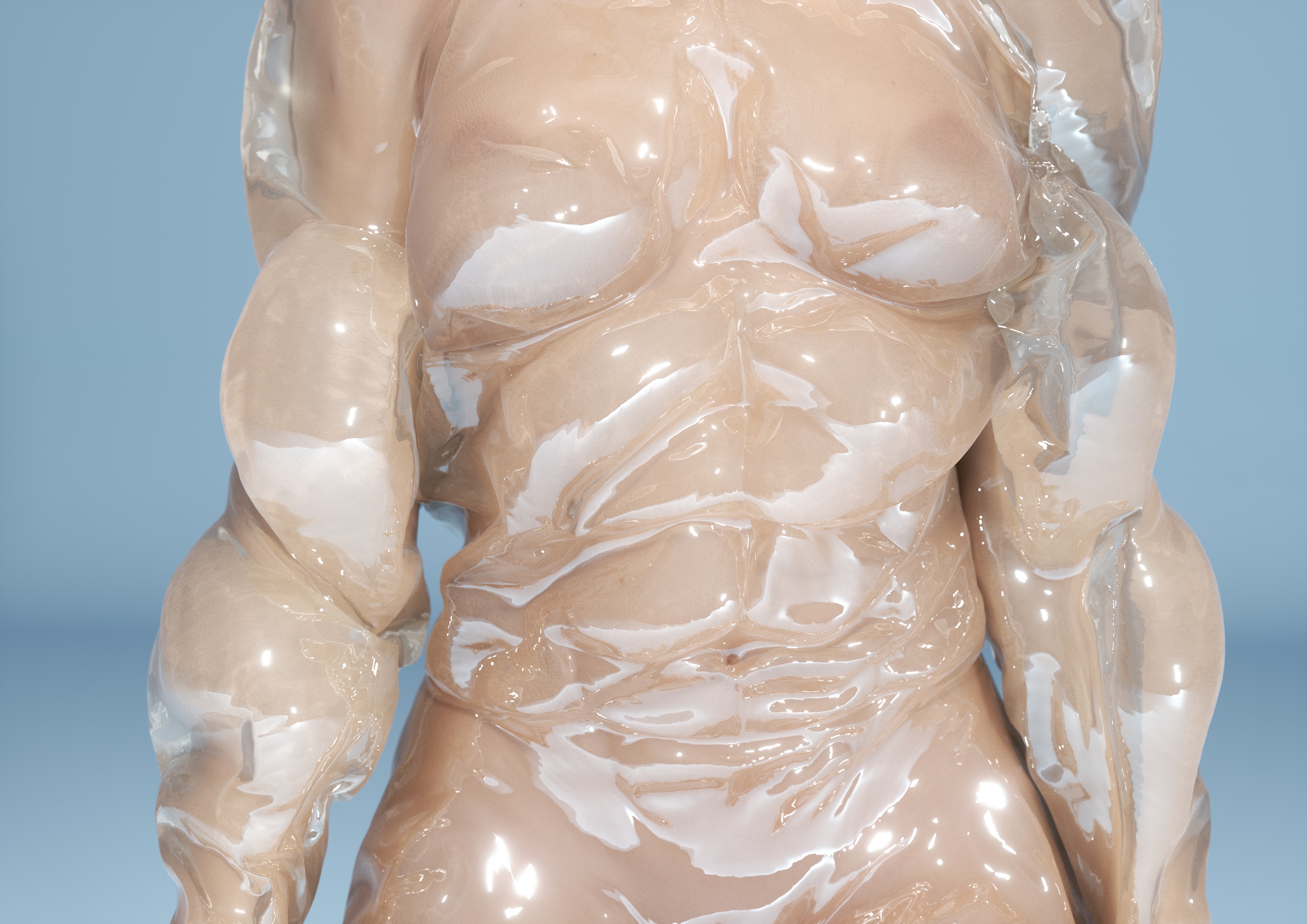

Both Cooper and Lek use their work as psychedelic portals; their large-scale immersive video installations critique complex political and economic systems with absurdist narratives that are seductively rendered through digital imaging software. Sensory overload mixes with dystopian plotlines and hazy ethics to create an emotionally turbulent viewing experience that both distorts and opens up our understanding of the present. Cooper creates highly emotive digital avatars that hover between perfection and the grotesque to bleed out the violence of labour and its impact on the female body; using video game software, Lek renders unstable sci-fi scenes that become stand-ins for the icy architectures of corporate capitalism.

- Kate Cooper, Symptom Machine, 2017. Courtesy the artist

Entering into Cooper’s current show in Hayward Gallery’s HENI Project Space, a world of gesticulating CGI bodies leaps out from a trifecta of screens. Piercing blue eyes smeared with blood and the peeling zombified flesh of a limp hand draw a ready contrast with a grinning mouth showing off its shiny new braces. Meanwhile, a character trapped in a transparent body suit attempts to wriggle free of her aesthetic torture chamber as it rapidly morphs between body types. Set against a guttural soundtrack composed in collaboration with electronic musician Bonaventure, Cooper’s characters are literally crushed by the forces of desire and the impossible pursuit of perfection fuelling the beauty industry.

Meanwhile, Lek’s new feature-length film AIDOL (2019), recently on show at Sadie Coles in London, presents a different type of personal enhancement. It follows Diva, an aging pop star seeking the support of AI songwriters for a comeback concert in 2065. Across environmental implosions of jungles coated in snow, the architecture of modern Southeast Asia melds seamlessly with that of global capitalism—the gargantuan forms of mega-malls and super-stadiums glisten across the screening room backlit with an eerie blue.

“I came here to learn how to create, not to predict the future,” a drone explains cooly as the camera pans around a room coated in QR codes. In Lek’s glossy dystopia, the quest for stardom eclipses the burgeoning sentience of artificial intelligence. The all-at-onceness feels sickeningly excessive, but there’s a darker side to it, an unspoken conviction that when shit finally does hit the fan, it’ll most likely pan out something like this. “It’s time for you to leave,” the drone insists, with the tone of a Tinder date turned sour. “I haven’t even learned anything yet.”

For all the meaty questions that AI: More than Human skimps on, it does include a deliciously creepy video work by Lauren McCarthy. Lauren (2017) saw the artist install cameras, microphones, speakers, and other electronic devices in stranger’s homes, acting as a 24/7 embodied Amazon Alexa. Replacing AI software with a real human, it becomes evident how strained this domestic relationship truly is—for both robot and resident. The project also inverts the classic dichotomy between AI devices and their human agents: instead of making the ghost in the machine ever more life-like, Lauren was an attempt to transfigure human into robot.

New York-based Ian Cheng’s AI project BOB

—currently on show at the Venice Biennale—takes the topic of AI’s emotional intelligence to an interactive level. BOB, an acronym for bag of beliefs, is a three-eyed algorithmic creature of vague reptilian status, caught somewhere between a snake and a caterpillar. Limbic motivators propel the creature in as many as twenty-five different directions, as it’s guided by a system of fundamental needs: hunger, sleep, sunlight, exploration. Like humans, BOB is prone to emotion, inspiration, manipulation, trust, and the breaking of it. Visitors to the show can interact with the touchy-feely worm via a “BOB-device”—otherwise known as an iPhone 10—and enter into its hypersensory psyche.

On a sunny spring day last year, desperately fiddling with the phone at Cheng’s Serpentine Gallery exhibition, BOB became a weird moment of kaleidoscopic self-reflection. Witnessing its full spectrum of mood swings: the almost stupid joy, inexplicable tantrums, and a total defiance of my attempts to reign it in, I understood Cheng’s paternal protectiveness over the algorithmic creature. Equally, I was aware of the cruelty of its white cube birth, which, in a sense, can be understood as a microcosm of the social pressure we apply to AI today—what it can or can’t or ought to (not) do.

The most meaningful AI-inspired art twists the operating logic of this technology to ask us: what’s the friction point of being human in the age of AI? How does this technology support the violent political and financial forces dominating our lives in the present? How does it morph and distort our bodies, digital and otherwise? And like all systems of belief, what does its increasingly complex psychology end up revealing about us?