When visiting a museum show it is expected that a certain amount of context will be inferred before a visitor has even crossed the threshold. This often stems from the knowledge of a broader historical or sociopolitical backdrop, but occasionally it can be the result of a media frenzy. For Art and China after 1989, which is now open at the Guggenheim Bilbao, the latter is certainly true. In the lead up to the show’s New York counterpart, protests began before it even opened, driven by concerns about animal cruelty. This ultimately led to the removal of three works and saw much debate around the idea of free speech for galleries and museums—with artists such as Ai Weiwei taking the side of the gallery.

For the Spanish iteration, the presentation of Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other was never on the cards, according to curator Alexandra Munroe, but the two other controversial works—Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World and Xu Bing’s A Case Study of Transference—have been included. In fact, Huang Yong Ping’s installation, featuring two cages (one actually has a separate title: The Bridge) that hold a selection of insects, arachnids and reptiles, takes centre stage at the opening to the Bilbao exhibition, and has lent its title to both versions of the show. It is a bold move, considering New York was forced to pull the piece, and it is difficult to keep this context from colouring any view of the work. During the exhibition tour we’re asked to consider the artist’s investigation of panopticon architecture (the original all-seeing eye) as well as notions of community, hierarchical culture and the chaos of humanity, but I’m wholly distracted by a large beetle which is flailing on its back, unable to right itself.

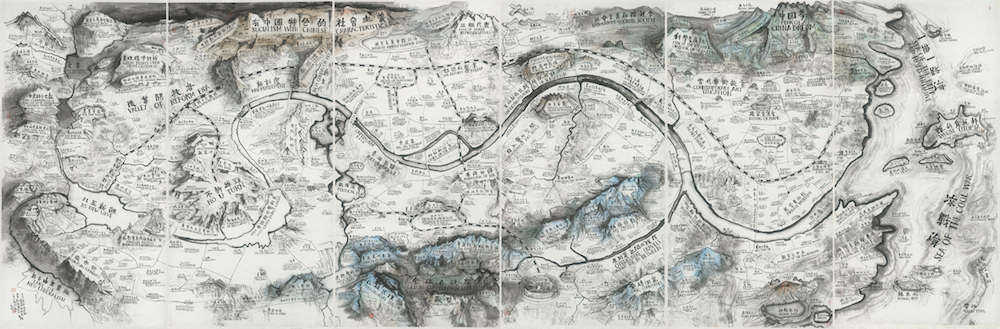

Beyond this obvious headline there’s an incredible swathe of works on display, defined by two major events in recent Chinese history: the Tiananmen Square protests (1989) and the Beijing Olympic Games (2008). This is where the issue of context comes into play again, as much of the cultural and political environment that frames these experimental artists’ practices remains something of a mystery to your average European. For immediate reassurance, Qiu Zhijie’s specially commissioned ink map (shown alongside Huang Yong Ping’s piece) displays significant political and cultural events throughout China and the rest of the world in the 1980s, focusing on their intersection with the visual arts.

There are six broad thematic sections that follow a rough chronology and highlight key milestones, but the sheer volume of work leaves little room for assiduous reading—which is no bad thing. The first main gallery is divided into two sections that highlight the importance of the major exhibition China/Avant-Garde, which took place at China Art Gallery in Beijing and heralded conceptual and experimental art in the country, alongside the events of Tiananmen Square and its aftermath. Wang Xingwei’s subversive painting of assassinated penguins and Wang Guangyi gridded portrait of Mao are shown alongside Zhang Peili’s absurd video of a bedraggled bird being washed in a bowl and Gu Dexin’s grotesque, melted plastic objects. It’s a sensory overload, setting the tone for a show that jets off at breakneck speed and expects you to keep up.

Some have alluded to the New York show as being something of a timeline, dictated by the fixed, spiral route visitors must take. In Bilbao this strict narrative is replaced with somewhat fractured wayfinding between galleries that are full to bursting. It is overwhelming but completely unavoidable as the exhibition covers such a massive cross-section of artists and roots them within international art history. At times it is even slightly anxiety-inducing, as exhaustive wall texts and carved-out subsections clamour for attention. In reality, it is best to give yourself over to the experience and read up later.

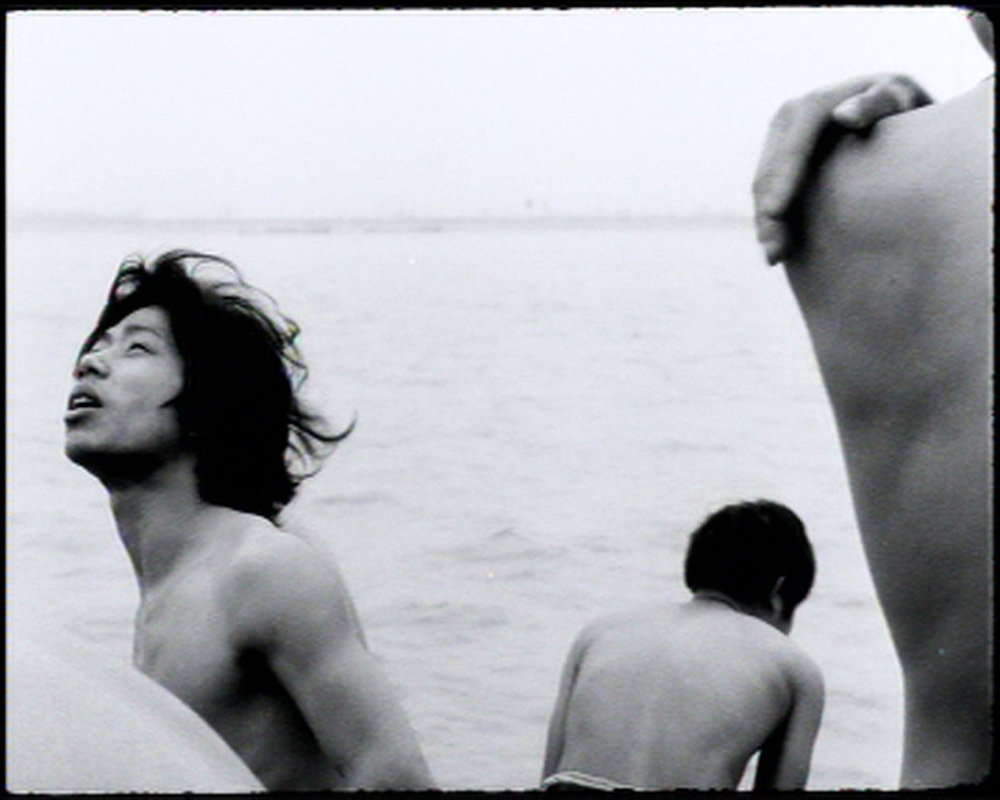

As one would hope from a show that emphasizes groundbreaking work, there are outstanding pieces that are compelling without context. Video and photography take precedent; often serving as documents for the broad forms of performance art that typified the period. Zhang Huan’s bizarre film To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain shows a group of individuals strip, before building a flattened human pyramid in an attempt to add their desired measurement to the landscape. The action is disarming in its discomfort and utterly futile. Nearby, Rong Rong’s stunning black and white photographs document the “East Village” community, so named due to the explosive impact of Ai Weiwei’s return from the New York district to work in the artistic area of Dashanzhuang. His images move past pure documentary and enter the world of staged tableau. A shot of a nude man stood before a lunch table is absolutely breathtaking.

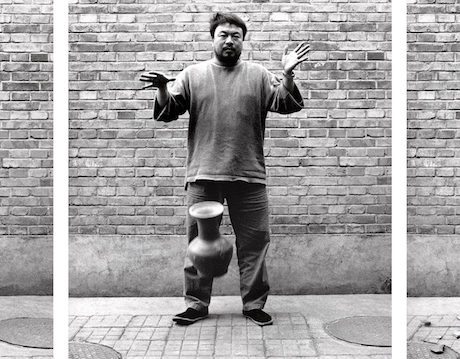

Naturally, one of Ai Weiwei’s best-known works is also featured. The three-part print titled Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn shows the artist doing exactly that. This bold act of iconoclasm directly questions what is deemed acceptable in terms of cultural deference and historical value—this work is now priced higher than the value of the original Han vessel.

Munroe is also keen to point out that Ai Weiwei is the only official “Chinese dissident” featured in the exhibition, and not all of the artists on show are directly concerned with politics and government affairs. Yan Lei was more preoccupied with the newly “global” attitude of his peers during the nineties, following the inclusion of three artists in the major Pompidou exhibition Magiciens de la Terre and another fourteen at the 45th Venice Biennale. His contempt for this clamour for international acceptance led to a series of counterfeit Documenta invitations (one of which is on display) and other wry pieces such as Appetizer, which consists of white powder carved to spell “Biennale” on top of a metal tray.

One final, significant work comes from Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, in a small, succinct space. Their video, Freedom, records the phenomenally ambitious installation that lets a highly powered hose loose in a sealed off room. Constrained in part by a hook, the tube thrashes like a wild animal due to the sheer force of the water pressure, as the room slowly fills up. When viewed in person, the piece can only be seen through tiny portholes in the walls, as if this menacing, manufactured beast could be a real threat. The process is addictive to watch, and I can’t help but feel that Freedom is an accurate summation of the exhibition experience. This show is filled with powerful, energized art and ample historical framing, which has all been compressed and funnelled through a single conduit that at times seems unwieldly. It doesn’t make the content any less compelling, but you need to be careful not to drown.

Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World

Until 23 September at Guggenheim Bilbao

VISIT WEBSITE