‘Self-Determination’, a core principle of the post-1945 international legal order – defined as the right of peoples to freely determine their political status and enshrined in Article 1 of the UN Charter – might seem an inapt and unusual title for an art exhibition. It has a legalistic specificity, which seems somewhat out of place in a gallery. However, this seemingly unusual choice serves to underscore the multifaceted intersections between legal and artistic realms, challenging conventional boundaries and prompting a reevaluation of the ways in which legal concepts manifest within the context of art and culture.

As Adom Getachew’s foreword to the exhibition catalogue for ‘Self-Determination: A Global Perspective’ at IMMA demonstrates, self-determination has always been a malleable principle, one which has been adapted to serve different political and artistic agendas. As Getachew notes, the principle was famously invoked by US President Woodrow Wilson in his ‘Fourteen Points’ address to Congress in 1917 as a means of promoting the strategic interests of the US empire by “contain[ing] the threat of revolution” in Europe. Wilson never actually used the term, and nor did he intend it to apply to everyone, as was clear by the US response to the 1919 Egyptian Revolution. While Wilson had never actually used the term, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the Russian Bolshevik leader, had explicitly spoken of “self-determination” in his The Right of Nations to Self-Determination (1914), in which it was figured as a distinctively revolutionary concept, one which should be instrumentalists to accelerate the demise of empires on the way to building complete communism. The concept of self-determination has a strong normative appeal but is capable of embracing (and being embraced by) contradictory political tendencies.

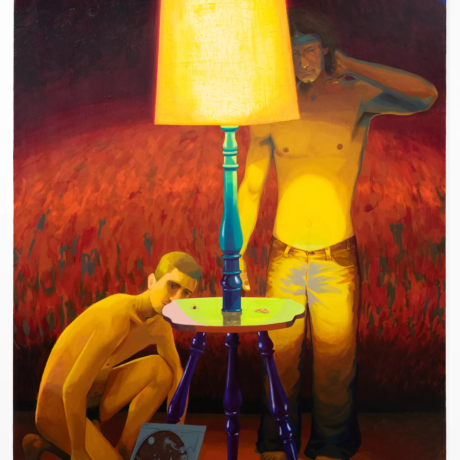

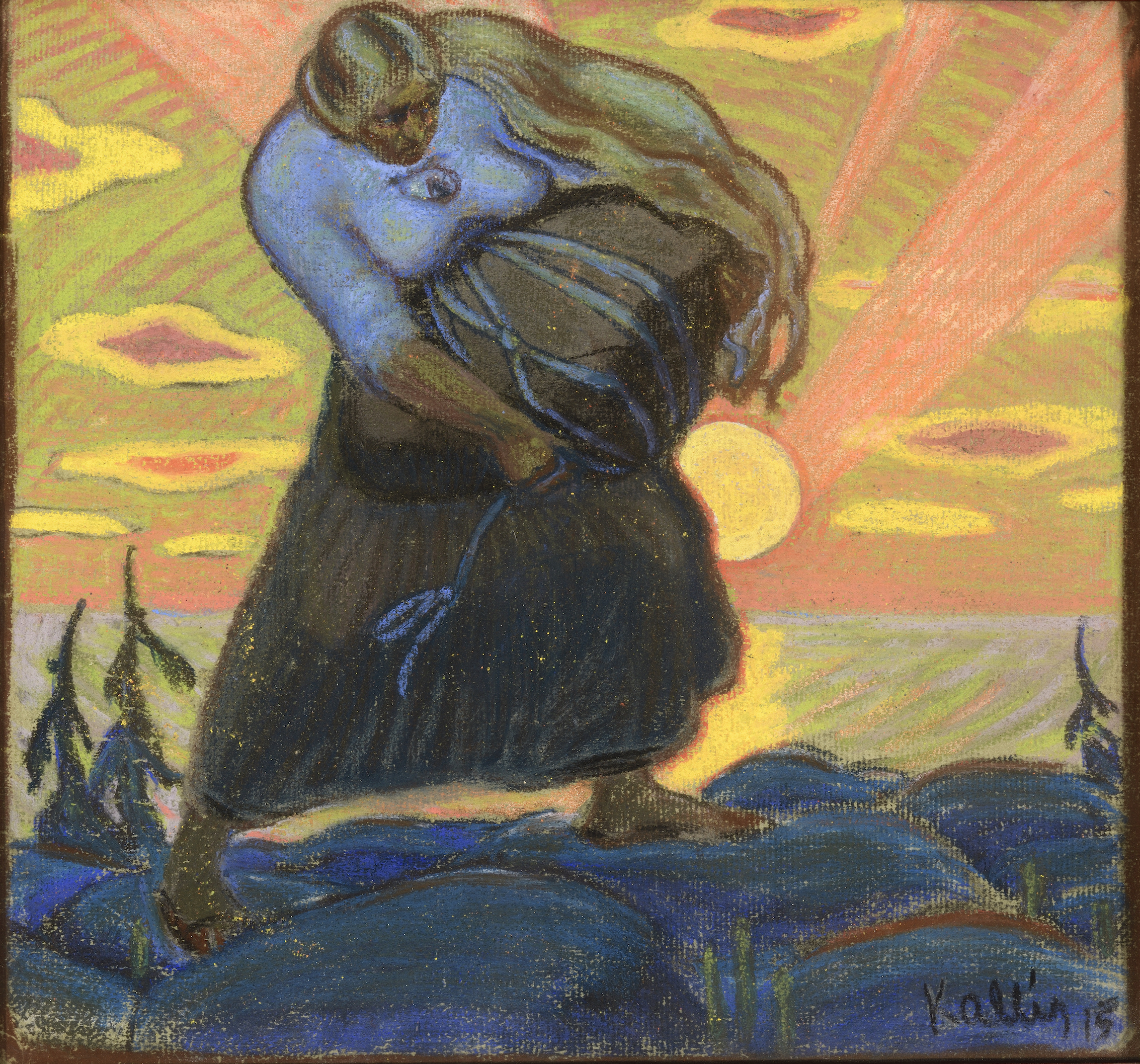

The malleability and indeterminacy of the concept of self-determination suit the IMMA exhibition well. The exhibition itself is a speculative survey of how nations and peoples dealt and continue to deal with imperial rule in their struggles for self-determination and how art and culture might be used to forge national identities. Across IMMA’s three main gallery spaces presenting 100 artists and collectives, ranging from historical figures like Alvar and Eino Aalto, Ilmari Aalto, and Jack B. Yeats to contemporary artists such as Ursula Burke, Banu Çennetoğlu, and Sasha Sykes, the exhibition explores ways in which artists from across nations grappled with the challenges of (re)defining their identity in the aftermath of war, censorship and occupation: how nations understood the formation of a new state, how their artists and poets imagined it and how artists today deal with these legacies.

The exhibition coincides with the centenary of the establishment of the Irish Free State and seeks to tie past struggles to present realities, be that Kurdish, Palestinian or Saharawi self-determination, Scottish independence, or Taiwan’s pursuit of international recognition. It recontextualises pieces from museum collections from around the globe alongside newly commissioned works by IMMA. It follows a series of talks and workshops as part of a three-year initiative leading to the major exhibition. Conference papers shaped the exhibition’s themes and publication, exploring theorists and discussions of art’s role in the global context of post-World War I movements for independence. The conference covers a wide array of topics, ranging from the League of Nations and its plans for the Palace of Nations in Geneva to the construction of the Stormont complex in Northern Ireland. Contributors explore the role of art in presenting a positive image of Ireland abroad, the limits of self-determination, and the deployment of culture for ideological and political interests.

Benedict Anderson’s concept of an “imagined community”, as explained in Imagined Communities (1983), is useful precisely because it reminds us that the state and the nation are contingent, cultural creations built on shifting sands: they are shared artefacts that can be recreated and reimagined by members of the community. The act of imagining the nation might draw on past historical material. In Ireland, a renewed focus on folklore, language, and artistic traditions, coupled with a romanticised celebration of Celtic heritage, served to reclaim and reinvent aspects of culture eroded under British colonialism. This cultural revival played a pivotal role in shaping a distinct Irish identity, laying the groundwork for subsequent political movements. Similarly, Egypt’s Pharaonic Renaissance in the early 20th century marked a revival of ancient Egyptian culture, driven by a quest for national identity and independence from British colonial rule. Mahmoud Mokhtar’s ‘Egypt’s Awakening’ (1928) is a representation of this cultural revival in the exhibition, depicting a partly unveiled woman alongside the Sphinx, symbolising the melding of modernity with Egypt’s ancient past.

Alternatively, the conception might depend on a radical departure from the past. “La Turquie Kemaliste” is a publication that emerged during the years 1934-1937, providing insights into the socio-political and cultural transformations taking place in Turkey under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, initiated a series of radical reforms known as Kemalism aimed at modernising and secularising the country. The regime, advocating for a complete break with its history, relocated the capital to Ankara and promoted a vision of European culture conflicting with Muslim Anatolian traditions. The regime’s social engineering, including a language reform in 1928, aimed to diminish Islamic traditions and identities, resulting in widespread illiteracy overnight.

The emergence of new regimes and the accompanying power struggles could potentially offer a more inclusive vision of the nation. A stand-out painting by Oksana Pavlenko, on loan from the National Art Museum of Ukraine, titled ‘Women’s Meeting’ (1932), embodies the intensified women’s movement during the Ukrainian-Soviet War (1917-21). The painting depicts women and children standing in front of a poster that reads, “The Success of the Revolution Depends on the Participation of Women”. New commissions and works by artists practising today respond to ongoing struggles within states. Minna Henrickson’s wall drawing explores the limitations of the State regarding women’s rights in both Ireland and Finland. The work illustrates the gradual erosion of women’s civil rights, highlighting the loss of agency and autonomy over time. Turkish artist, Banu Cennetoğlu’s installation titled ‘right?’ (2022) is a piece inspired by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Each letter of the declaration is spelt out with a golden balloon that will deflate through the duration of the exhibition, a poignant reminder that fundamental rights should never be assumed or taken for granted. Slovenian artist Jasmina Cibic’s two-channel video ‘Beacons’ depicts eight women translating speeches from the 1985 conference of cultural workers in the Non-Aligned Movement. The participants, representing the global South, the Middle East, South-East Asia, and former Yugoslavia, proposed strategies for the survival of non-Western art and culture. Filmed against isolated architectural backdrops immersed in nature, the film aims to reintegrate the absent female voice into the narrative of world-building history.

It is important to note the concept of self-determination, often viewed as a progressive and radical principle, can also be utilised in service of counterrevolutionary agendas. Fearghal McGarry points out the seven rebels associated with the Abbey Theatre who were involved in the Easter Rising, which was then harnessed to a conservative vision of a new state divested of its radicalism. In 1919, Irish politician Arthur Griffith, founder of Sinn Féin, incarcerated in Gloucester, emphasised the need to ‘mobilise the poets’ to garner global recognition for Ireland. Griffith underscored the significance of artists, writers, designers, and musicians in Ireland’s quest for recognition as the first state to break away from the British Empire. The exhibition prominently features renowned Irish painter Sean Keating. His painting, ‘Men of the South’ (1921), captures the spirit of Ireland’s independence struggle within the ranks of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which emerged as the military wing of Sinn Féin during the Anglo-Irish War (1919-1921) and the subsequent Irish War of Independence (1919-1921). The conflict led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, resulting in the establishment of the Irish Free State and the partition of Ireland. Keating’s ‘Night Candles Are Burnt Out’ (1928–1929) is also featured in the exhibition, depicting the groundbreaking Shannon Hydro-Electric Scheme and symbolising Ireland’s modernity and self-sufficiency beyond engineering feats.

Amongst the contemporary artists featured, Palestinian artist Larissa Sansour and Danish artist Søren Lind’s film ‘Familiar Phantoms’ (2023) documents recollections of Sansour’s childhood in Palestine juxtaposed with the harsh realities of displacement. In December 2023, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination, with one hundred seventy-two countries in favour and four countries voting against it, including the US and Israel. Is it the prerogative of Israel or any other state to dictate Palestine’s self-determination? Contemplating the notion of a state involves questions of its originators and beneficiaries, and ‘Self-Determination – A Global Perspective’ successfully urges us to envision a revolutionary moment, a ‘tabula rasa.’ This prompts a crucial inquiry: what fills this blank slate?

Exploring the mechanisms to achieve such a reset, contemporary art often falls short in projecting future visions. Instead, the pressing concern emerges: can art catalyse the ‘tabula rasa,’ the revolution necessary for perceiving and actualising new statehood visions? Given Palestine’s current lack of self-determination, the role of art and culture in realising this aspiration becomes a pivotal and complex consideration.

‘Self-Determination – A Global Perspective’ at IMMA is fractured, reflective of a world as fractious and dangerous now as it has been in our lifetimes. It is challenging to conceive of the stable idea that new states can be established in this era, and when contemplating the idea of imagining the state, questions arise: for whom and by whom? Can artistic expression truly define and fortify a nation’s journey towards autonomy and cultural resilience? The exhibition observes and evaluates the influence of art in shaping the identity of a nation and is a must-visit for artists and those interested in reexamining dominant historical narratives. The exhibition delves into the transformative power of art in shaping a nation’s identity, recognising artists as potent witnesses and allies in the ongoing struggles for rights and autonomy. ‘Self-Determination – A Global Perspective’ at IMMA, Dublin, runs until the 21st of April 2024.

Written by Sofia Hallström