Art or porn?

One day in the office of the indie-film production company Forensic Films, Charles Atlas heard one of the producers say, “Wouldn’t it be great if we did a series of porn videos directed by artists?” A golden opportunity for the filmmaker, who raised his hand and said, “Me! I’ll do it!” It was 1998 when Atlas—the New York-based artist well-known for his works featuring drag queens running around the Meatpacking District—was shooting the gay porn movie Staten Island Sex Cult inside a brothel. “I remember at the time thinking, ‘Here I am; I’m spending six months editing a porn film, and Bill Viola is having a show at the Whitney. That’s the difference.’”

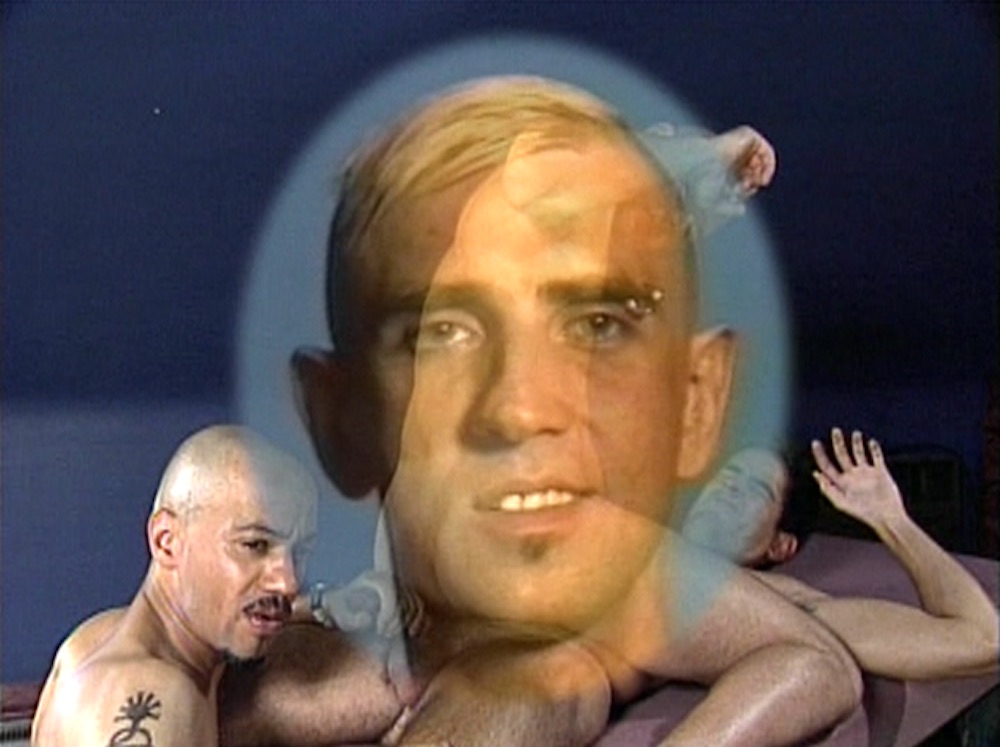

Staten Island Sex Cult shows the adventures of members of a secret society who believe that the energy released by their sexual activity will enable them to teleport themselves to an alien “father ship”. Which is precisely what happens in the final scene: after an abundant orgy, the protagonists get beamed up to an UFO, leaving the room full of extra-terrestrial vapour. The work is a weird combination of sci-fi and pornography, with a propensity for foot-fetish sex: as group leader Stinkmetal asserts, “Nothing like the smell of fresh feet in the morning to jump start a man’s day!”

- Charles Atlas, Staten Island Sex Cult, 1998

According to my pornographic knowledge, Staten Island Sex Cult was the first artist porno ever distributed by a production company. Despite the commercial purpose (to satisfy customers’ masturbatory urges), the film narrative is eccentric and imaginative (writer Laurie Weeks collaborated on the script, while pop musician Marc Almond made a few songs for it). So the question is inevitable. Where is the border between art and pornography? Can the artistic genius sublimate what is commonly regarded as obscene?

Docu-porn and kinky role models

“Without the pioneering pornographers who changed what we thought was indecent […], I could never have had the nerve to make my movies,” director John Waters confesses in his 2010 book Role Models. To Waters, such role models include the gay porn directors Bobby Garcia (“the Almodóvar of Anuses,” he calls him, “who has blown hundreds and hundreds of really cute marines and lived to tell about it”) as well as David Hurles (“an inspiration to my inner filth for years,” he admits). Porn, after all, has its classics like any respected film genre. In 2015, the Baltimore-born artist hosted Groundbreakers on Playboy TV, in which he presented seminal works of pornography, like Deep Throat (1972)—which is for porno what Breathless is for Nouvelle Vague.

It was perhaps Bobby Garcia’s mouth skills that inspired Waters to shoot one of the most disturbing sex scenes in cinematic history: in Pink Flamingos (1972), his scandalous masterpiece of trash, drag queen Divine gives a blow job to her son who, enraptured by pleasure, screams, “Yes Mama, I’m yours.” (I wonder if Waters ever heard of Colby Keller, a thirty-eight-year-old artist and gay porn star. In his latest project, Colby Does America, he travelled around the US to create art-porn videos that he posted online. Among the highlights is Colby masturbating in the middle of a dreamy landscape populated by deer.)

“Can the artistic genius sublimate what is commonly regarded as obscene?”

If for Waters pornography is a priceless source of creative inspiration, for Israeli artist Omer Fast it would seem to be the target of a documentary impulse. His Everything That Rises Must Converge (2013), a digital film installation made up of four simultaneous synchronized projections portraying twenty-four hours in the life of four LA porn actors. As we follow the narrative, from the moment when the actors wake up in their apartments to the explicitly sexual scenes, we viewer-voyeurs are constantly bewildered by the contrast between their daily activities (taking a shower, cooking a meal, watching TV) and the pornographic bits culminating in the epilogue’s foursome.

But that’s not all. Fast complicates the plot by adding other fictional sub-tales about three characters in crisis (a traumatized adult-film director, an actress reciting a piece about rape and a woman who attempts to get the attention of her cheating husband). The four stories overlap and unexpectedly converge: reality (the porn actors’ lives) and fiction (the non-pornographic narratives) collide and blend together, the first serving as raw material for the second. The artist’s “pornographic imagination”, to quote Susan Sontag, ennobles and sublimates the roughest X-rated scenes.

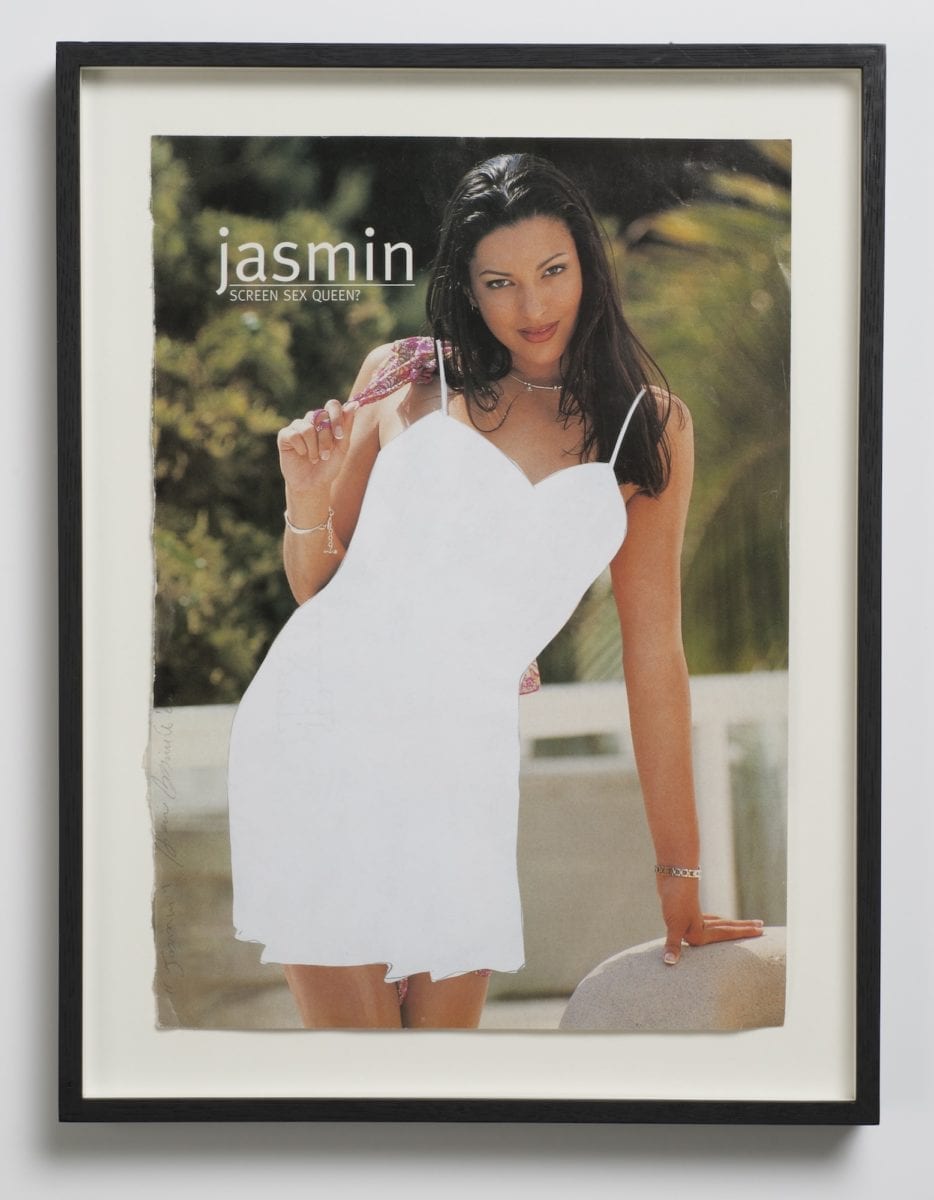

- Left: Pierre Bismuth, Elisa, 2004. Right: Jasmin, 2004. Courtesy the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels

The porn punctum

“In a porn photo, the punctum is the detail that does not arouse. It neutralizes desire, and by that act of clemency […] surreptitiously reinstates and intensifies passion,” poet and critic Wayne Koestenbaum wrote in an article recently published in Spike Art Quarterly. Implicitly alluding to Roland Barthes’s notion of punctum—the detail in a photograph that, like an insect’s sting, catches the viewer’s attention—the American writer tells us that what makes the pornographic image deeply captivating, rather than the pure depiction of nudity, is the non-sexual component (an object in the background or a particular shade of colour, for instance) which adds meaning and complexity to the picture: in other words, a certain art.

Pierre Bismuth seems to know this very well, as proved by his series of works Collages for Men (2003). Here the French artist has enlarged shots from porn magazines and covered the women’s bodies with white paper cutouts in the shape of a dress or a bathing suit, in an attempt to replace the “missing” clothes. If no display of nudity is given to our lustful eyes, we cannot help but linger on the details that surround the female silhouettes: a Christmas tree, a waterfall, the flat surface of a swimming pool. The pornographic image is first of all a photographic image, dealing with composition and chiaroscuro issues—like any other photograph. That sounds like a revelation for the viewer blinded by desire: as Koestenbaum points out, the punctum can save us “from tumbling into a libidinal abyss”.

“The artist’s ‘pornographic imagination’, to quote Susan Sontag, ennobles and sublimates the roughest X-rated scenes”

However, the porn punctum can be something other than a single detail inside the picture. According to Koestenbaum, it is also “the unsuspected colours (ultramarine, burnt umber, alizarin crimson) that secretly give the figure its conspicuous liveliness”. Such a chromatic liveliness is a typical trait in the paintings by South African artist Marlene Dumas, who has made public displays of nudity one of her main artistic interests. In her studies taken from mass-produced pornographic images, naked women masturbating or revealing their sex are sketched out through quick, liquid brushstrokes in a vibrant palette of grey, brown and blue. Fingers (1999), showing a female figure from the backside while she is jerking off, sublimates the porn image into an impressionist picture made of seductive violet and blue marks. As the artist herself said in an interview, “If you look at Fingers closely, there are no genitals there. That little painting exposes nothing really. It is quite abstract. Very gestural. It is all about suggestion.”

Spiritual porn

However hard to imagine, porn has a spiritual side. Nudity and worship, orgasm and mystic ecstasy can be intimately intertwined. My mind goes to Derek Jarman’s debut film Sebastiane (1976), co-directed with Paul Humfress and shot entirely in Latin, which portrays his main character—the former Roman soldier and Christian martyr Sebastian—as a man consumed by his Christian piousness as much as by his homoerotic impulses.

An even tighter bond between the spiritual and the sexual informs the whole oeuvre of French writer and artist Pierre Klossowski (1905–2001), whose “theo-pornology” (as defined by Gilles Deleuze in a 1965 text) has left a permanent mark on the history of erotic art. Obsessed with the moral tension between bodily and spiritual pleasure, Klossowski spent the years of the Nazi occupation in France studying as a seminarian in a Dominican monastery. After the war, he quit religion and wrote an acute essay about the scandalous writing of the Marquis de Sade. By combining theological debate and pornographic imagination, the author-artist plumbed the recesses of sexuality with an inclination towards its most perverse, shameful manifestations.

“However hard to imagine, porn has a spiritual side. Nudity and worship, orgasm and mystic ecstasy can be intimately intertwined”

The protagonist of his trilogy The Laws of Hospitality is Roberte, an attractive, androgynous woman whose beauty is “of that sober sort which so often conceals pronounced tendencies to frivolity”. According to an agreement with her elderly husband (an eminent professor of scholastics), Roberte must offer herself to different visiting guests of the house in order to satisfy her own sexual desire as well as his voyeuristic pleasure.

In one of the illustrations that Klossowski produced for the book, The Parallels Bars, the half-naked Roberte is depicted strapped to a bar, while one man stares at her from below and the other voraciously licks the palm of her hand. The figures are contorted, their limbs elongated in a cartoonish way; the colour palette is soft and delicate, the style surprisingly naïve. Klossowski’s simply drawn forms evoke the uncorrupted art of children; innocence sounds like the flipside of perversion—there’s no contemplative experience, no spiritual catharsis without sin.

Art to have a good w**k to

When Guardian journalist Emma Brockes, in front of the Fiona Banner work Arsewoman in Wonderland, asked porn star Ben Dover, “Do you think it’s art?” he cheekily replied: “Art? It’s basically shite. I think the best that can be said for it is that you can probably read it and have a good wank.” The controversial work, presented at the 2002 Turner Prize, is a transcript of a porn film in pink capital letters on a huge billboard, describing the action in minute detail. I wonder (and I wouldn’t dare to consult Dover on this point), where is the punctum in Banner’s piece? Maybe in the vibrant, aggressive colour of the text? Or in the slightly curled corners of the billboard’s paper?

- Ed Fornieles, Truth Table, 2016

What makes this work a work of art, I would say, is the pornographic imagination behind it: the artist created a “wordscape” that blatantly discloses the voyeuristic mechanism of porn, pushing the language to the extreme limit of what can’t be said. Arsewoman in Wonderland would seem to highlight something even more. In the era of “sexting” and dick pics, Grindr and YouPorn, society seems to have taken a radical pornographic turn. A porn script printed on a big advertising poster shouldn’t look that outrageous, after all.

In 2016, British artist Ed Fornieles produced a VR installation (Truth Table) in which “users have the chance to occupy an ever-changing host of bodies locked in sexual embrace”. If the latest developments of contemporary art allow us to experience sex, the question at the beginning of this article sounds still pertinent: Where is the border between art and pornography, the high and the obscene? If notions such as “porn punctum” or “pornographic imagination” do not sound right to you, I would suggest you ask Ben Dover. This time he might surprise you.

This feature originally appeared in issue 34

BUY ISSUE 34