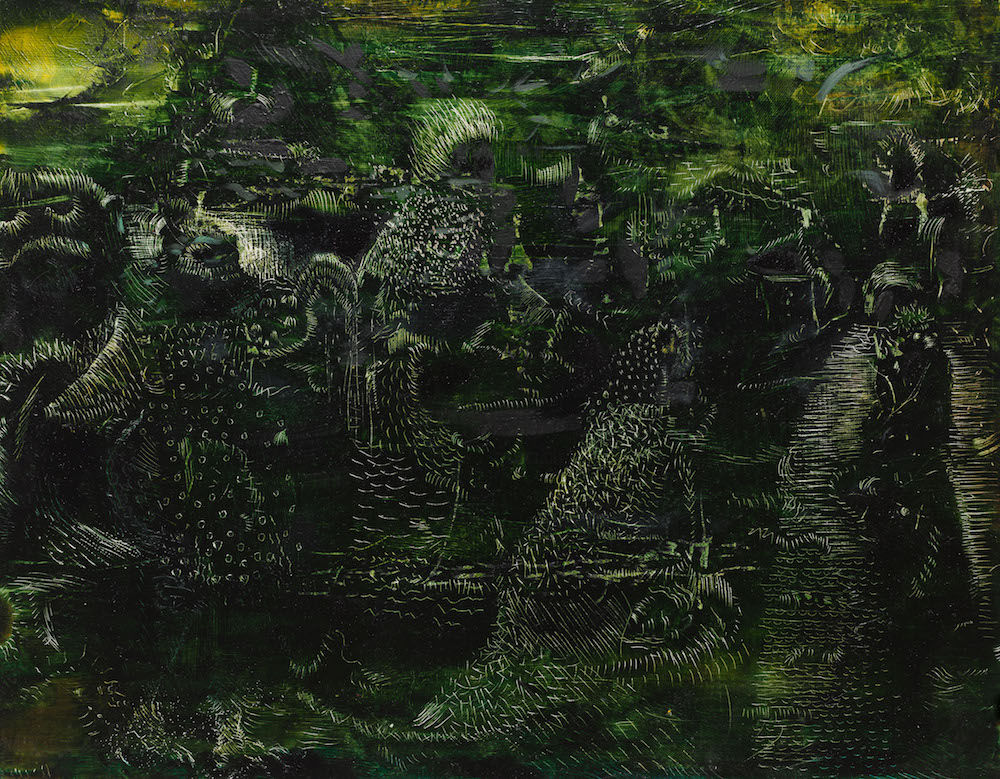

Sound is not something people tend to connect with painting. The countless museum canvases that celebrate modern and contemporary icons are, for the majority, silent symbols of their artist’s original actions. Yet Tehran-born, New York-based artist Ali Banisadr explains his works as coming from vibrations that are embedded in his mind. Less violent than the tremors that tormented his adolescence, the noises that come to him now are more consoling, symphonic even. His paintings—currently showing at Het Noordbrabants Museum, in Hertogenbosch, Holland—are, as he explains them, born of the animated insides of his mind, that seem ready to riot.

- Installation view by Joep Jacobs

Can you explain the nature of this show? Given the choice of works, are we looking at a retrospective here in Holland?

This exhibition is my first museum retrospective in Europe. It brings together a decade’s worth of paintings and drawings from 2008 until now. It’s been great for me to have this chance to reunite with some of the older paintings that I haven’t seen since they left the studio. The catalogue that accompanies the show includes an essay by the art historian Robert Hobbs.

“To have the chance to be in the city where Bosch painted centuries before, and to visit his original studio, was an honour”

I want to understand the location of the exhibition. It might initially seem to be a mismatch, but the more one comes to understand your work, the greater the synergy is with the institution and its remarkable collection. How important was that to you when we can see traces of Hieronymus Bosch, Peter Snayers and Sebastian Vrancx in your work?

The location was important for me because of its history—I made a visit to the fantastic Bosch exhibition a few years ago now, and was immediately taken by the museum, and the quality of its collection, and also found the city to be a very special place. So I was delighted to hear that the museum was interested in doing a show, and it only felt natural to exhibit there. To have the chance to be in the city where Bosch painted centuries before, and to visit his original studio, was an honour. Also having the show in Holland where a lot of my favourite painters come from was another plus, from Bosch to Rembrandt to Willem de Kooning.

In the accompanying exhibition video you talk about the invasive sounds of war from your adolescence in Iran, and about how noise has become the nucleus of what appears on canvas. Are the sounds violent or much more visceral, as reflected in the overall atmosphere of your paintings?

The sounds and vibrations from the explosions during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war had a profound impact on my childhood, and the way I dealt with the destruction was to retreat into my own world to try to make sense of my surroundings. At the time with my having to take refuge in the makeshift shelters, the isolation drew attention to the sound—of the vibrations rather than the visual experience. Such viciousness tormented me for years after, but not necessarily in a violent way. Since those memories were based on sound, they were, as you observe, more visceral. So when the noises manifest themselves in the work it’s more of a guiding force that enables me to draw everything together, becoming almost orchestral. And the sounds don’t solely reflect a particular time or place—they inform a combination of many experiences.

If sound is your spark, how do you deal with it becoming entirely silent in your paintings?

I seek a silence that is achieved by having a flow of air through the paintings without any obstacles. When I finally achieve that on canvas, there is a quietness to the overall feeling of the painting, and when I arrive at this point I know the painting has reached its conclusion. The work ends up being an ordered disorder, and although there are still notes of sounds as the eye moves over the painting, since there is a rhythm, the sound becomes quiet and is contained within itself.

“When the noises manifest themselves in the work it’s more of a guiding force that enables me to draw everything together, becoming almost orchestral”

Does beauty belong in your work, or are these scenes more brutal?

As with anything in the world, you have to see both sides of the coin in order to get the full picture. Beauty and brutality often need to exist together, and I want to see them side-by-side. I always think about that quote from the actor Bruce Lee where he talks about emptying your mind, and being formless and shapeless like water. Having said, “Water can flow or it can crash, be water my friend.”

Ali Banisadr: Foreign Lands

Until 25 August at The Het Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch

VISIT WEBSITE