Perhaps the most gruesome image from the latest series of Stranger Things is a lump of flesh, seen slithering along a tarmac car park, before slowly descending down a drain cover, leaving a lingering smear of gristle and slime behind, along with one chunk of bone. Flesh and meat are well-worn tropes within the horror, sci-fi and thriller genres—in this case, a robust monster is formed from the combined flesh of his mind-flayed victims—but it is beloved by artists too.

It makes sense that lumps of flesh should feel violent and scary, yet many of us purchase them on a regular basis in neat packets from the supermarket, slices of raw animal somehow appearing sanitized in this form. The line between clean (and, as many will see it, delicious) meat and grisly flesh is often a fine one—though many artists skirt the issue of meat production altogether, using fleshy substances to comment on everything from cultural taboos to colonialism and old age.

“It is very important to point out that my subject is painting and flesh—not meat!” says Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão when I refer to the forms in her work as the latter. In many of her paintings, gutsy slices and tears in the canvas provide openings for gristly flesh-like forms to peak or cascade out. “Since the beginning of the nineties, [my works have] connected the idea of flesh with the wounds of colonialism in Brazil. Wounds that are still open today… The body that I am referring to is a political body.”

“It makes sense that lumps of flesh should feel violent and scary, yet many of us purchase them on a regular basis”

The visual punch of Varejão’s works is undeniable. Before interviewing the artist a few years ago, and knowing little of the context of the work, the implicit violence was immediately present. I have always viewed the fleshy forms that spill out of the cracks and surfaces in her works as representing gruesome things that are hidden, which can’t help bursting out. What does it connect for her?

“I think of it as an opposite process,” she tells me, “that is, ‘going into’ the painting, taking us from the insensitive objectivity of the surface to the red sensibility of the interior. My painting is located between tactile, visual and plastic sensuality and reason. There is a hyperbole of matter and tactile exacerbation that relates my work to the Baroque and reaffirms the theatricalization of painting. In this Baroque game there is always a contraposition between the geometrical exterior—cold, modularly constructed—of the geometrical surface of the tiles and the warmth and the sensuality of the body.”

“I think we live in terrible, difficult times—it’s part of the baggage we bring to looking,” Anish Kapoor explained when he displayed his “meat paintings” at Lisson Gallery in London in 2015. “I’m not going to exclude it. But I’m not going illustrate it either… I don’t want to have anything to say, it just gets in the way.” For this exhibition, Kapoor displayed three enormous, weighty canvases loaded with paint, resin and silicon that resembled chunks of meaty flesh; white fatty gristle and all. They protruded thickly from the walls, quite literally referencing the horrors that paint has depicted throughout history, with all coyness and subtlety removed.

“I’m obviously very engaged with bodily things,” Kapoor continued, “and all that has led me to this place—a fascination with red which I’ve had over many, many years. Of course, red has a terrifying darkness in it which I’ve always been fascinated by. So does all that coming together make it a commentary about the current state of the world? Perhaps, but it’s not for me to say. I feel that that ties the work down too hard. One wants to open the story, not close it.”

“Red has a terrifying darkness in it which I’ve always been fascinated by”

Zeng Fanzhi’s meaty paintings were inspired directly by the butchering trade, and were prompted by seeing workers lying on frozen carcasses at a local butcher to avoid the summer heat. He told the New York Times of the mixed emotions that followed. “Some feelings were of hunger, because I was hungry in those days, others were of horror, as the blood of the meat would stain the people laying on them. I think this is why I use a lot of red in my work, it fascinates me.”

As well as often depicting skin in his paintings in very fleshy, red tones, the artist has painted carcasses on numerous occasions; sometimes he paints them hung closely together, sliced-open, at other times he mixes half-dressed human forms with them, man and meat combining to unnerving effect. There are numerous biblical references in these works too, and a nod to the often brutal human condition.

Rather than just depict the appearance of meat, some artists have used it as a material, most often in connection with the human body—live and dead flesh in stark contrast with one another. Carolee Schneemann did so with quite literal joy, in her much referenced Meat Joy (1964), a performance involving eight performers (including the artist), traditional art materials, raw fish, meat and poultry. The apparent horror of some of these materials makes the vital performance highly confrontational, bringing together sexuality, zest for life, death and cultural taboos in one wild act.

“I wonder how viewers would respond to the dead flesh in this work if it were made now”

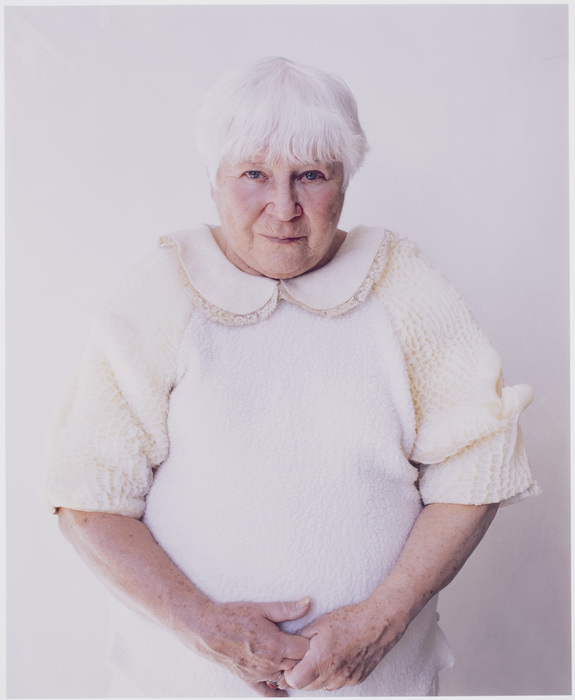

I wonder how viewers would respond to the dead flesh in this work if it were made now, at a time when meat itself is far more politicized, for both environmental and ethical reasons. “I am really not interested in the politics around meat as something edible,” says Turkish artist Pinar Yolaçan, whose series Perishables depicts elderly bodies clothed in meat garments—featuring frills made of raw chicken and neat scarves formed from innards. The meat clothes in her images often reference the physiology of the wearer and, of course, the title and inclusion of dead meat in Perishables also points morbidly to the age of the wearers, and the way their bodies are often viewed.

“I was nineteen when I began experimenting with food as a perishable material in my work,” she tells me. “So it didn’t start with meat per se but as I experimented, it became one of my primary materials. It is a material to me, as some artists use bronze or wood or clay. I really see it as an organic material with impermanency, and as something that shapes itself with the passage of time.”

In the series Maria, Yolaçan photographed African-Brazilian women in intense portraits that reference Old Masters paintings and the Romantic genre. “When you put on the clothes of another culture, it changes how you stand, how you feel, the gestures you make,” she said at the time. The garments are made of expected and unexpected materials, from regal velvet to placenta and tripe. “Through this series Yolaçan engages with issues of beauty, the body, colonialism and death as a way of broaching the ‘impermanence of things’,” wrote CCA Lagos, which showed the work in 2010.

In some cases, it’s the artist themselves who don the meat—in the early 2000s, Zhang Huan clothed himself in a muscular “meat suit”, exaggerating the human form with rippling bulges of bright red flesh. He walked around New York in the suit, and at one point set a white dove free. The performance brought together Buddhist tradition, ideas around the animalism of humans and comments on bodybuilding within American culture.

Perhaps the most well-known meat-wearer of all is Lady Gaga, who turned up at the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards draped in an animal’s worth of flesh from head to toe—including hat and boots. The outfit has since been taxidermied, and is “living” out its days at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. Almost ten years later, it seems likely the response to a garment fashioned entirely from meat might be ever-so-slightly more vitriolic if it were to be paraded at an awards event. Just like the real thing, blood and guts are ever-evolving, as much a reflection of our inner state as our own fears, desires and taboos.