A bunch of flowers sits on the windowsill in Russian artist Daria Neretina’s studio. Plant cuttings and splashes of ink add colour to all corners of the room, where she is the latest artist to make herself at home as part of the Elephant Lab residency programme. She has travelled from her home in Moscow, bringing with her an array of personal fabrics taken from her family home with a view to introducing these to her delicate, intensely personal work. The legacy of folk craft runs deep in her embroidered textile pieces, and her approach goes against the grain of the fast pace of modern life. Instead, she works slowly with her stitching, inspired by the naive icons of Italy, Greece and Russia, which were richly decorated with beads and embroidery and most often created by non-professional painters.

Inspiration comes from the rhythms of nature, and while in London she has explored everywhere from Kew Gardens to the Barbican Conservatory. Weeds, vegetables and flowers form the basis of her research, and one former residency took her into the heart of the Moscow Botanic Garden. Neretina’s mixing of these elements hints at the magic of an elixir; potent, carefully composed and ever-evolving over time.

What have you been working on while at the Elephant Lab residency?

Before I came here, I knew I wanted to be working with fabrics. I brought tablecloths from my Grandma’s house and I decided to find some old fabrics here too. I went to Portobello Road and bought a really beautiful old tablecloth. And then I was able to add to that all the really great materials available here—canvases, oil, acrylics. I’m used to working with volume, with 3D works, because I often create installations by mixing bits of porcelain and bits of old glass. So I wanted to mix that up with my painting and make something a little bit different. But of course, when you’re painting on soft surfaces, everything is different; it’s an interesting experience.

“It’s about a connection with the material. You are like two different authors, and if you try to beat it your work will not be good”

Why did you choose old tablecloths as the fabric you wanted to work with?

This fabric is familiar, it’s really close to me, because I spent so much time in my Grandma’s house, and all the time this tablecloth was on the table. I think we can find inspiration in these old things. I like working with old materials and mixing them with modern elements to create something new. I like to prolong their life. I did a bit of research of fabrics when I came here. I went to the V&A and to Liberty’s—it’s interesting, they’re new but the style feels older. They could have been produced twenty years ago or 100 years ago. The technology is different but the patterns remain. I was inspired by the wallpapers of William Morris, and I decided that I wanted to do something in his style but mix it with bright colours.

You talk of using materials from your Grandma’s house, and of stitching and embroidery being part of your work. What appeals to you about this element of craft and folk tradition?

In the end, it really is craft. It’s about a connection with the material; when you start to work with it, you and the material are like two different authors, and if you try to beat it your work will not be good. You need to understand the material. Embroidery used to be so popular when it was normal to spend all your time doing it. Ten years ago, I didn’t feel able to spend so much time on my artworks. Now I love it and I hate it. But you have to think about how much time you’re willing to spend in preparation to get the result you really want.

What else were you inspired by to create your works here?

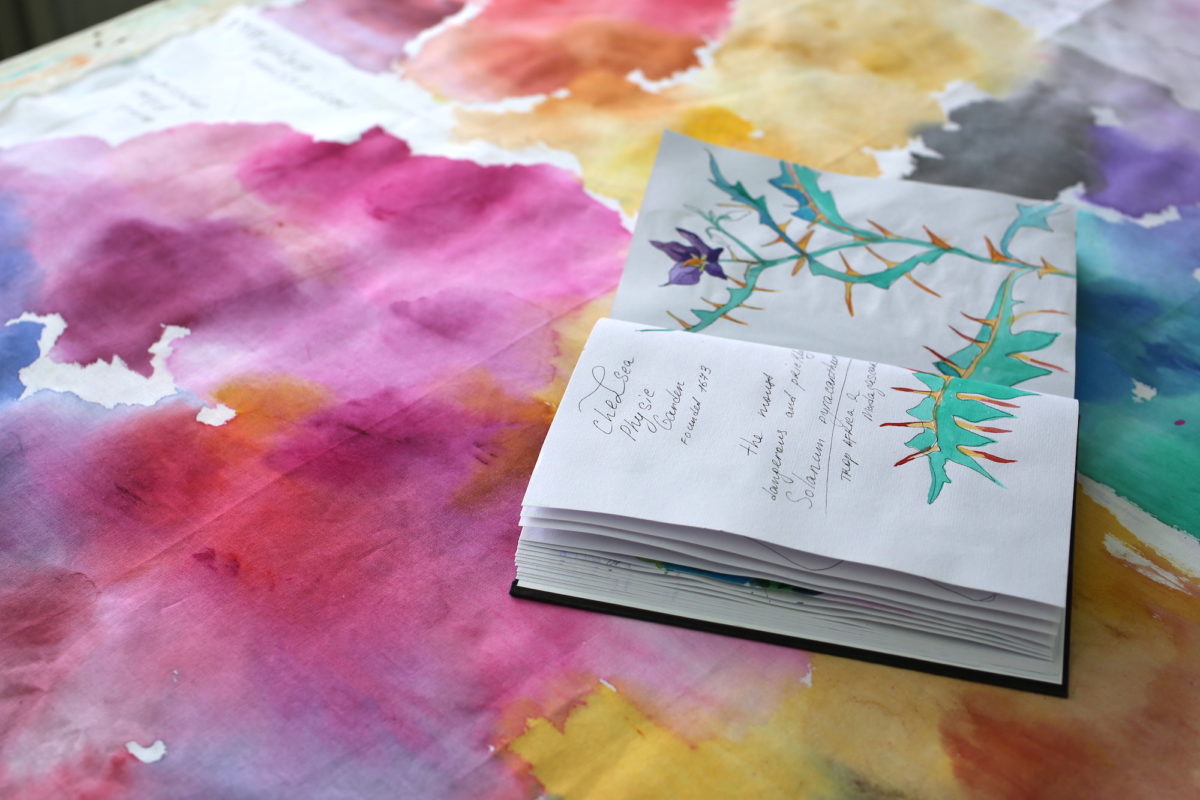

I was also inspired by the botanical gardens and parks in London. I visited the Barbican Conservatory, and visited the parks, and Chelsea and Kew Botanical Gardens. I went and saw the plants there and was really drawn to the sunflowers, the artichokes and the lotuses, even though they were all in the last days of their life. It’s interesting in these English parks because they’re created designed and planted by humans but ultimately they’re governed nature. And nobody was cutting these plants back, even though they were in the less beautiful stages of their lives. It felt like part of the transition of real life. And I decided to mix the colours of the dried plants and flowers and mix it with really bright colours.

How did this interest in botanics become part of your work? How much is it a part of your daily life?

I’ve always been drawn to using images of food and nature in my installations, things like seeds, fruit and vegetables. And now what I’m doing is a little different, but comes from the same principle of exploring how much the end of life is also a part of life. I went to visit Highgate Cemetery. It was a strange experience, because it is one of the most sorrowful places but also a really peaceful place. Two minutes away is a big park where you can spend time playing games or with a barbecue. There’s no real distance and split between these natural places of life and death, which I find really interesting.

“This mix of life and death is part of our experience, and that idea is everywhere”

I did a project in a greenhouse in the Moscow Botanic Garden. People can go in there but it’s mostly a scientific space, where they’re working with plants. I found this space that was mostly just being used as the rubbish space—when they cut the plants down and back, they put it all there. I cleaned the space, and found a really big collection of old flowerpots. I mixed these in with new ceramic objects that I produced, and put them in position with the old cut flowers. It felt like this real mix with the dead plants; this mix of life and death is part of our experience, and that idea is everywhere.

In some botanical spaces, they work really hard to keep the plants and flowers under control; it looks idyllic, like paradise. But it doesn’t feel normal or real. In ordinary life you can’t see everything in that way, no matter where you are—normal life can’t be an idyll. My mum has her own garden, and she likes to spend all her time there, but she feels ashamed that everything is not like paradise. She wants to show everybody that it’s perfect, but I want to say to her, it’s ok; it’s normal. Nature is wild.

Photographs by Louise Benson

Residencies at Elephant Lab

Practising artists are invited to make proposals for a one month residency at Elephant Lab.

APPLY NOW