We take a closer look at a trio of coincident solo shows part of the museum’s Autumn/Winter exhibition programme to examine how they capture the evolution of the medium within a society in perpetual flux

Ever since its inception, photography has served as a means of documenting the facets of the reality around us. Nicéphore Nièpce, the Frenchman behind the earliest surviving camera photograph (1826-1827), used that shot to depict a bucolic window view in Le Gras, his hometown in Burgundy, France. Obtained through an exposure of several days, the image was captured on a pewter plate coated in bitumen diluted in lavender oil. Nièpce’s experiments perfected those of the British photography pioneer Thomas Wedgwood, who in 1800 had succeeded in producing temporarily visible, black-and-white negative scenes on silver nitrate-treated paper, or white leather, within a camera obscura — the “grandmother” of modern photographic devices. The French inventor was, in fact, the first one to discover a chemical solution capable of fixing photographs permanently, thus altering the course of history and the medium itself forever. He called that process “heliography”, a term stemming from the Greek words helios and graphê, which together translate to “sun drawing”.

From there, Nièpce joined forces with French painter and physicist Louis Daguerre to further develop the heliograph technique. After his death in 1833, it was Daguerre’s own turn to contribute to the advancing of photographic experimentation. With his invention, the daguerreotype, which relied on a silver-coated copper plate and iodine vapour to form a latent image made of silver iodide when exposed to light in the camera, the artist reduced exposure times to only a few minutes: a discovery that, having allowed him to win favour with the French government — and a life-time salary to make it available to anyone interested in using it — took the world by storm. In a matter of years, photography was used by painters who recognised the creative possibilities unlocked by it and budding image-makers alike, the latter of which turned to it to illustrate the rapidly changing sociopolitical, cultural, scientific and architectural reality of their era. Staying true to its original, wide-ranging scope, Deborah Turbeville. Photocollage, Richard Mosse. Broken Spectreand Mathieu Bernard-Reymond x La Muette — three of the exhibitions currently on view at Lausanne’s Photo Elysée — explore the past, present and future of photographic language through the filter of today’s most urgent issues.

The oneiric, spectral femininity of Deborah Turbeville’s timeless photocollages

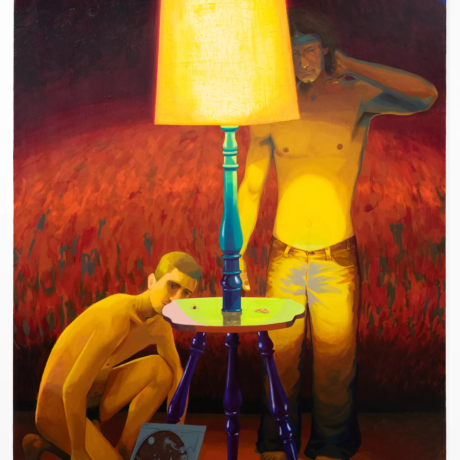

Had she not started out as a fashion editor on the editorial desks of Mademoiselle and Harper’s Bazaar, American photographer Deborah Turbeville (1932-2013) would have probably never fallen for the allure of the camera. Known as the eye who “transformed fashion photography into avant-garde art”, as Women’s Wear Daily wrote in 2009, the Stoneham-born image-maker ventured well outside of the prefixed schemes of glossy magazines. Having stepped into the creative industry in the early 1970s, Turbeville found herself in Guy Bourdin (1928-1991) and Helmut Newton’s (1920-2004) world: two of the personalities who, together with her, rewrote the fashion canons by adding a haunting, darker and more mysterious side to the editorials filling the pages of the most coveted publications of the time. Yet, rather than existing in the fast-paced, urban landscapes of Newton’s photography, or in the surreal compositions of Bourdin’s, Turbeville’s muses appeared to belong to a mental dimension, somewhere suspended between the dreamlike and the nightmarish.

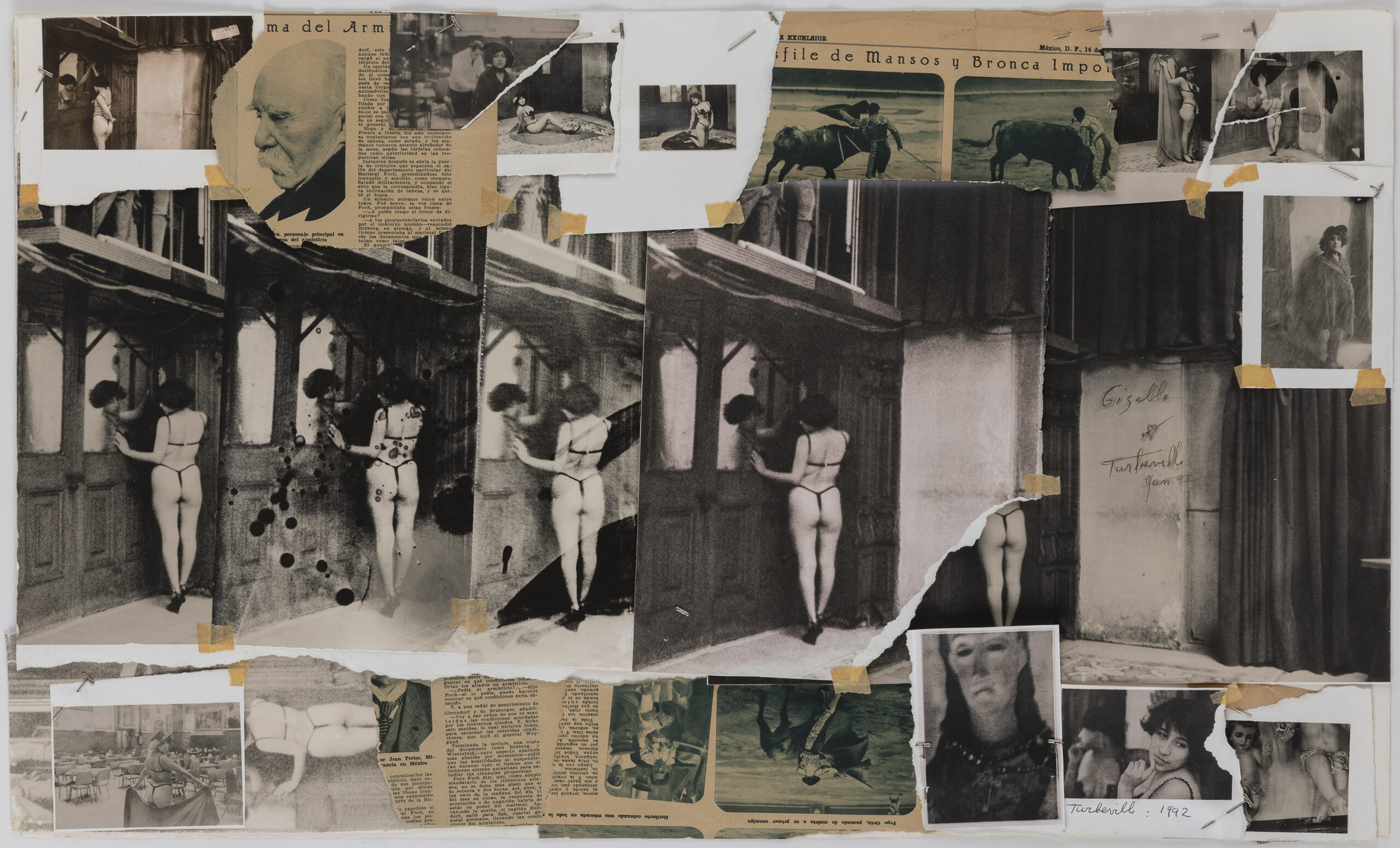

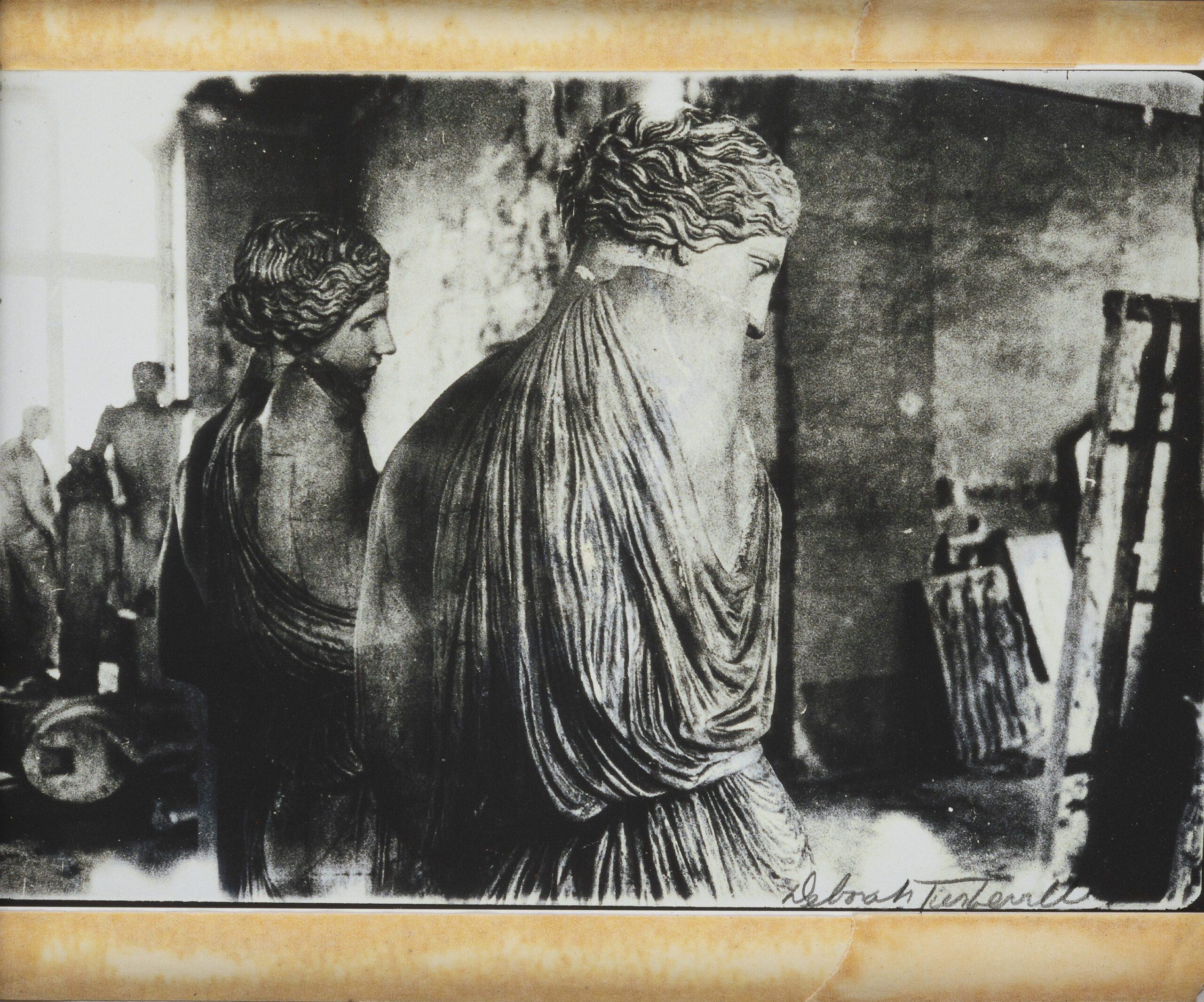

It isn’t a coincidence that Turbeville, one of the first female image-makers to land commissions on Vogue Italia and shoot campaigns for the likes of Valentino, strived to capture something else than beauty in her visual practice. Breaking with the hyper-sensual portrayal of womanhood embraced by the media of that period, the photographer went on to document the female sphere like no one had ever done before through her emotionally charged, psychological lens. At once visceral and melancholic, eerie and fascinating, her portraits of women centred around the exploration of human “matter” — from flesh and bones, hence the body and its manifold presence, all the way to our hiddenmost emotions, fantasies, hopes and fears. A master of monochromatic photography, Turbeville played with changing sepia hues, a dramatically contrasted greyscale and, more rarely, pastel shades to bring her sitters’ inner universe to life. In doing so, she rendered the multiple layers composing the female experience — starting from the most superficial ones and gradually working her way inwards — to provide an alternative to the appearance-focused, onedimensional representation of women.

Turbeville’s desire to redirect the attention onto the condition embodied by the female protagonists of her shots not only showed when she stood behind the camera, but it also translated into the laborious manual manipulation that shaped the post-production phase of her craft. Unlike her contemporaries, the image-maker’s style emerged from the physical reworking of photographic prints, which she scratched and wrote on, photocopied, cut and then pinned back together, creating visual sequences more inspired by cinema than by traditional fashion photography. An ode to her disruptive inventiveness, which even today remains largely overlooked, Deborah Tuberville. Photocollage establishes an implicit link between the American photographer and her historic forerunners. In my eyes, the thick, beautiful patina of her superimposed, evocative images recalls the worn texture of the shots taken by pioneering photographers Constance Fox Talbot (1811-1880), Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) and Virginia Oldoini (1837-1899): three of the first women to ever lay their hands on a camera and reinvent female portraiture through their rulebreaking gaze.

Despite only dating back to the late 20th century, Tuberville’s production carries a timeless essence with it. Whether produced as part of her fashion campaigns, like in the case of her Comme des Garçons (1980) series, or belonging to her personal archive, like her Unseen Versailles (1980) collection or L’Heure Entre Chien et Loup (1977) project, the image-maker’s photographs absorb the subjects portrayed in them into a haze that conveys the emotive turbulence, enigmatic nature and powerfulness of womanhood. Caught in moments of solitude or female camaraderie, lost in gothic nature or else juxtaposed with the raw interiors of decadent buildings, Turbeville’s women seem to be seeking a way out of the limiting reality allowed to them. Appearing as if alienated from their surroundings — an aspect accentuated by their often absent or distracted stare — the photographer’s heroines symbolise her own disillusionment with society. Through her imaginative practice, Turbeville not only set herself aside from the conventions of fashion photography by elevating commercial editorials to artwork quality, but she also paved the way for other image-makers interested in using the medium to expose the state of the world as we know it today.

Richard Mosse’s infrared images render the urgency of life in the age of climate disaster

As Photo Elysée Director Nathalie Herschdorfer eloquently writes in her introduction to the museum’s ongoing programme, “there would appear to be nothing in common between the work of Richard Mosse and that of Deborah Turbeville”. If the experimentation of the Irish artist falls under the category of photojournalism, the previous paragraphs have outlined how the boldness of Turbeville’s craft has allowed the American photographer to transcend definition, instead giving life to a visual genre of her own. And yet, the two image-makers appear to me more interlinked than they might seem at first glance. To bring their works closer together is, first and foremost, the dramatic intensity unleashed by their images. There where Turbeville zoomed in on the psyche of her female sitters by externalising the otherwise invisible tumultuousness of their existence into movement-filled, unearthly and deeply nostalgic ambiences, Mosse resorts to the advanced imaging technologies of environmental science — including multispectral, thermal and infrared cameras — to heighten the urge for immediate climate action.

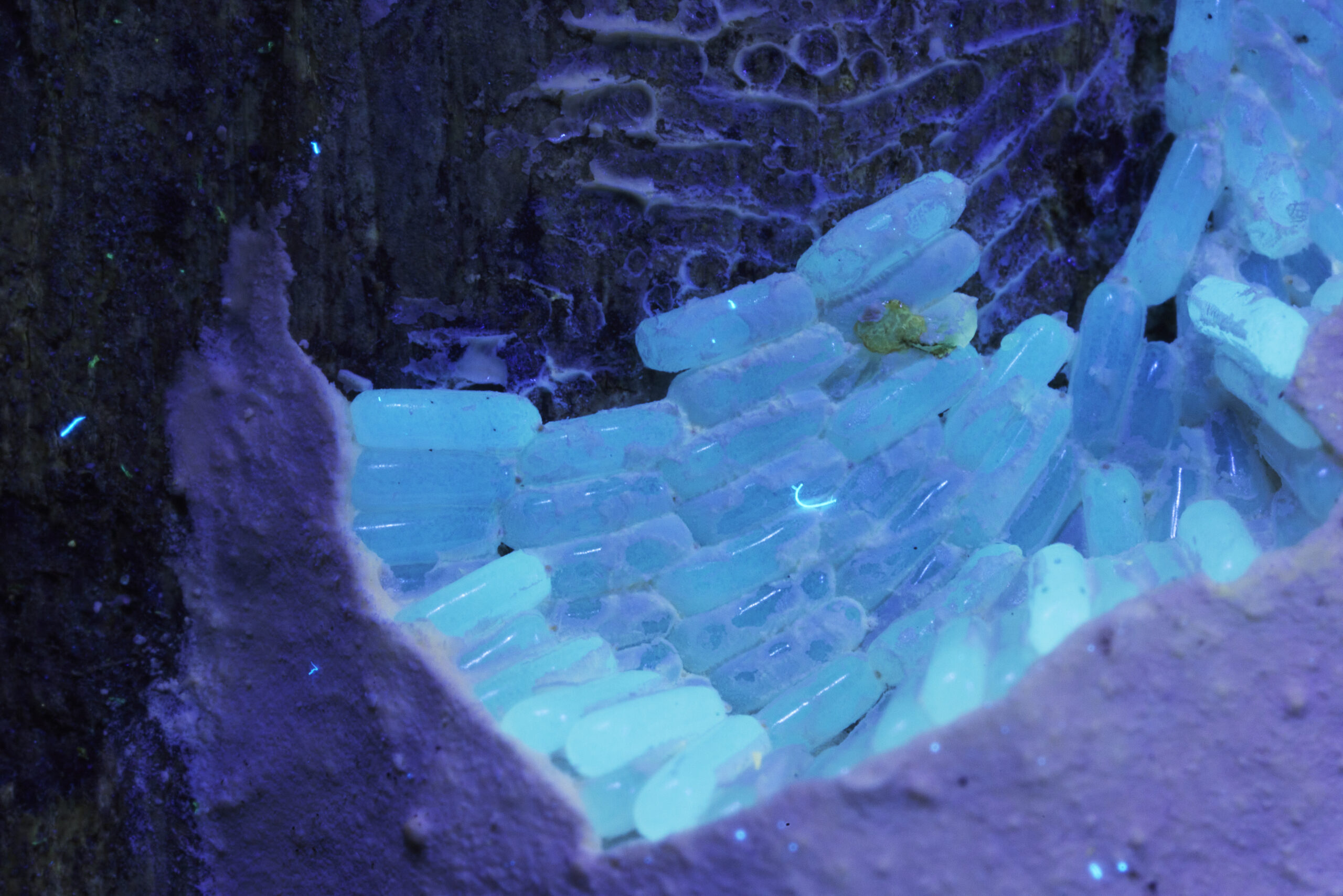

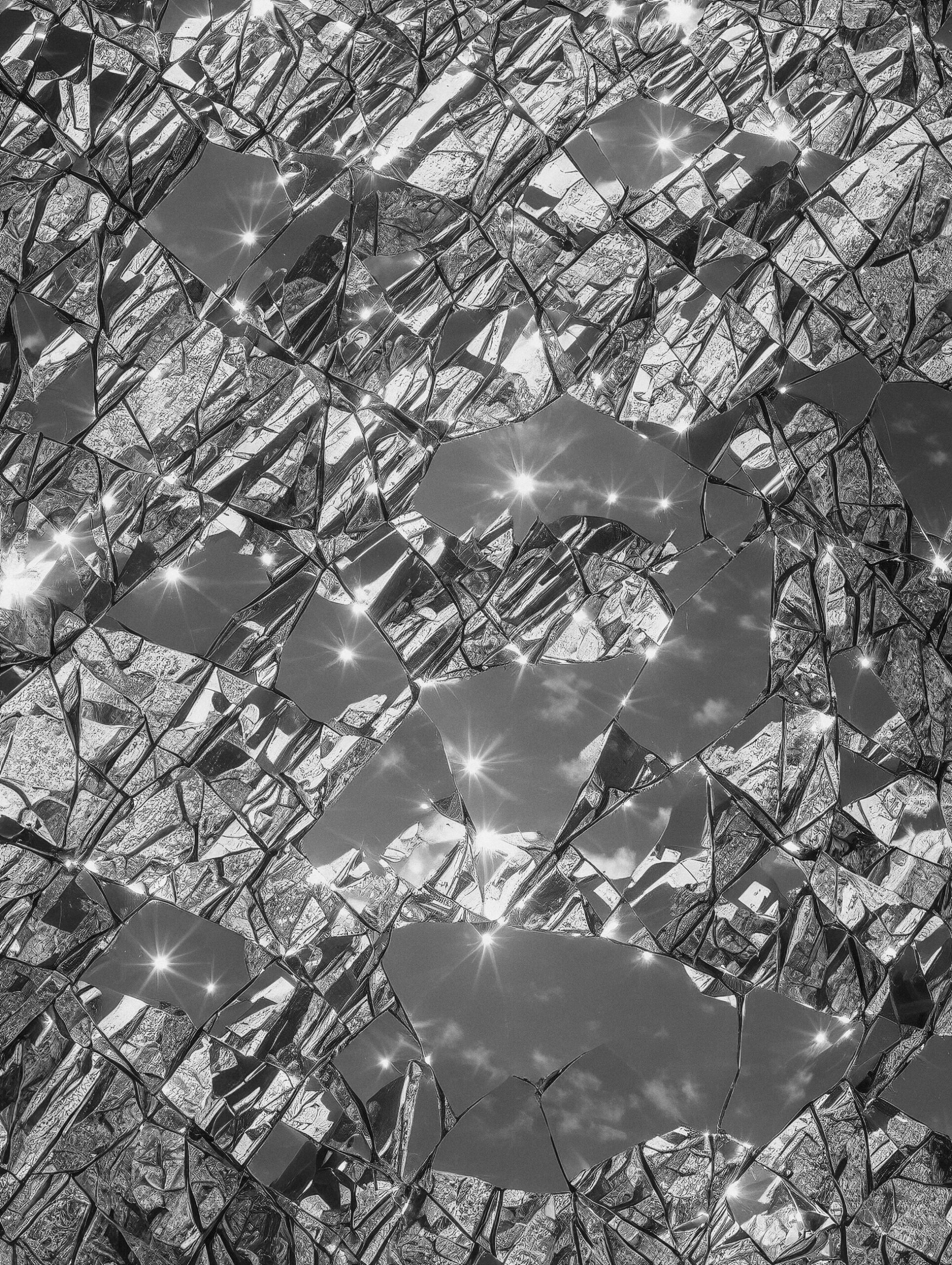

If the fashion photography disruptor leveraged her artisanal process to alter reality so as to reflect her own subjective understanding of it, in Mosse’s practice, it is impossible not to sense his awareness of and preoccupation with the impending environmental disaster. Presented for the first time in Switzerland as part of its eponymous solo show, Broken Spectre catapults viewers into the endangered heart of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Brought to the public in a monumental, 19-something-metre-long video installation, the film charts the different fronts of the ecological crisis in Brazil by exploring the deleterious link between deforestation and climate change. Screened next to each other in an entrancing visual continuum are microscopic, UV lamps-lit night scenes that show the activity of minuscule lifeforms inhabiting the floor of the cloud forest, aerial views assessing the damage already caused to the environment, and breathtaking clips delving into the once untouched and now scarcely surviving Amazon vegetation.

Lensed in striking, hypnotising tones of red, blue and green, Mosse’s masterpiece bears witness to the man-made tragedy that is the erasure of the world’s last great reservoir of biodiversity. It is a catastrophe that, unfolding before our eyes, was legitimised by the blind fight for profit at the expense of humanity itself. Faced with the illegal felling and burning of the forest, industrial scale agribusiness and toxic artisanal goldmining, the native populations living in the area — such as the Indigenous Yanomami community — are the most exposed to the aftermath of mindless anthropisation. Already threatened by the expansion of corporations and banks interested in turning their land into a money-making machine, with the worsening of the environmental emergency, Brazil’s oldest inhabitants are prompted with another challenge undermining their survival. Conceived as a wake-up call inviting “the audience to consider the magnitude of this global crisis”, Broken Spectre forces us to acknowledge our responsibility towards the planet, the species nurturing its ecosystems and our fellow humans to persuade us to reverse the geological decline before it is too late.

Placing faith in the power of photography and visual storytelling to inspire and mobilise the masses, Mosse’s contribution to halting climate change puts the latest technological image-making devices at the service of this struggle to reach the consciousness of each and every one of his viewers. Rather than looking at his output as a way of dissociate himself from the precarious world scenario, the Irish artist underscores the gravity of the current situation through his distinctive, neon-like palette, filling his eyes with both the beauty and suffering of the Earth. Not yet hopeless nor intent on turning away from the here and the now any time soon, Mosse embraces his work as a platform to cement the importance of a collective response to the environmental disasters of our era. How? By visualising the dangerous chain reaction enacted by them and how this is already affecting the lives of communities scattered around the world, and striving to lay the foundations for a better future.

Inside Mathieu Bernard-Reymond’s AI-generated, sublime mindscapes

Stumbling across the work of Franco-Swiss photographer Mathieu Bernard-Reymond was what persuaded me to analyse these three showcases as the past, present and future of the photographic medium, respectively. Again, while the direct connection between the works of Deborah Turbeville, Richard Mosse and Bernard-Reymond himself might not appear as evident to everyone, to me, the fil rouge weaving them together was undeniable. In the first one of the showcases presented in this article, I saw the dawn of photography as an “eye” through which to portray, at once, our inner and outer world. Starting with the production of early practitioners, portraiture has, in fact, always been one of the medium’s most prominent genres. Although the artistry demonstrated by Turbeville throughout her decades-spanning career put the very notion of portraiture to the test — her female muses were way more telling of the image-maker’s own dimension than they were a reliable rendition of their physical features — her practice laid great emphasis on the human element, which served as its main subject.

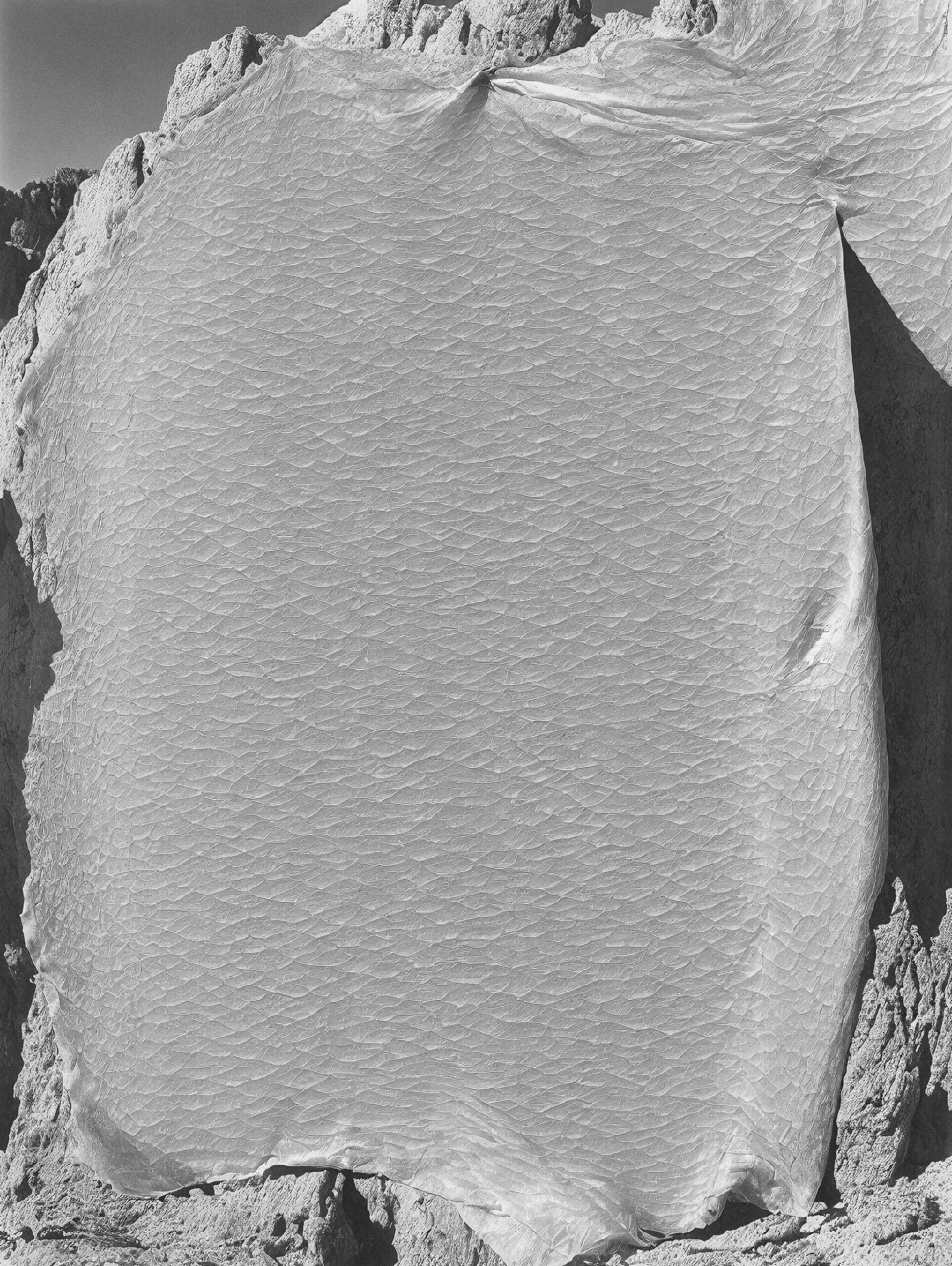

While one could argue that her uncompromising documentation of femininity forwarded a critique of contemporary beauty standards and the patinated society imposing them onto women, Turbeville’s oeuvre was still more focused on technical execution and aestheticism than it was on conveying any given message. As society evolved, so did its related issues, which inevitably insinuated themselves into the artistic discourse, becoming a core aspect of many disciplines. Broken Spectre — and Mosse’s wider experimentation for that matter — is the proof that, with the surfacing of new challenges, including the ongoing discussions around identity, sustainability, representation and activism, art can no longer serve its own sake. Instead, especially within the photojournalism field, today creativity and visual language are being drawn upon as means of capturing the criticalities of our times, gathering the public and institutional support needed to change things and envisioning new ways forward. Landed in the wake of this year’s AI euphoria, Bernard-Reymond’s D’après Ramuz (2023) series hints at what, in my opinion, will be the next chapter of the centuries-long journey that is photography.

A collaboration between the artist and Pully’s La Muette — literary spaces, the project took shape from selected writings of the acclaimed Vaudois author C. F. Ramuz which, “fed” to the artificial-intelligence tools utilised by Bernard-Reymond, restituted a selection of brand new images. Turning the selected quotes into black-and-white, fascinating landscapes, the photographer succeeded in giving a form to the mental visions usually appearing while reading a text. “Mathieu Bernard-Reymond aims to freeze those moments when unique visions emerge during the process of reading — moments when a metaphor fleetingly comes to life in the reader’s mind,” explains a statement released ahead of the opening of his solo exhibition. “These impressions often fade quickly with the flow of reading but gradually contribute to transforming the written text into a visual entity — a world of its own.” While the exponential rise of AI-generated visual projects was met with mixed reactions by the global artistic community, as also demonstrated by the World Press Photo’s decision to backpedal on its Open Format category and outrule the use of artificial intelligence from its annual competition; the medium’s potential can and should not be neglected. Compared to traditional photography, AI embodies an opportunity to envision realities that we have never before had the chance to touch with hand — or should I say eye? If chased responsibly, this dense trail of clues could fill the gaps of knowledge and awareness that prevent us from actively seeking an alternative to the ruling order of things, from imagining it, even. By allowing us to translate our words into a tangible vision, artificial intelligence could transform the numerous calls for action invoked by today’s climate and human rights activists into a concrete scenario. And just like we learn how to reproduce a certain note with our voice after hearing it played on the keys, perhaps being confronted with images attesting to the society we could be living in, if only we wanted to, could help us achieve the long-overdue change many of us are currently fighting for.

Words by Gilda Bruno